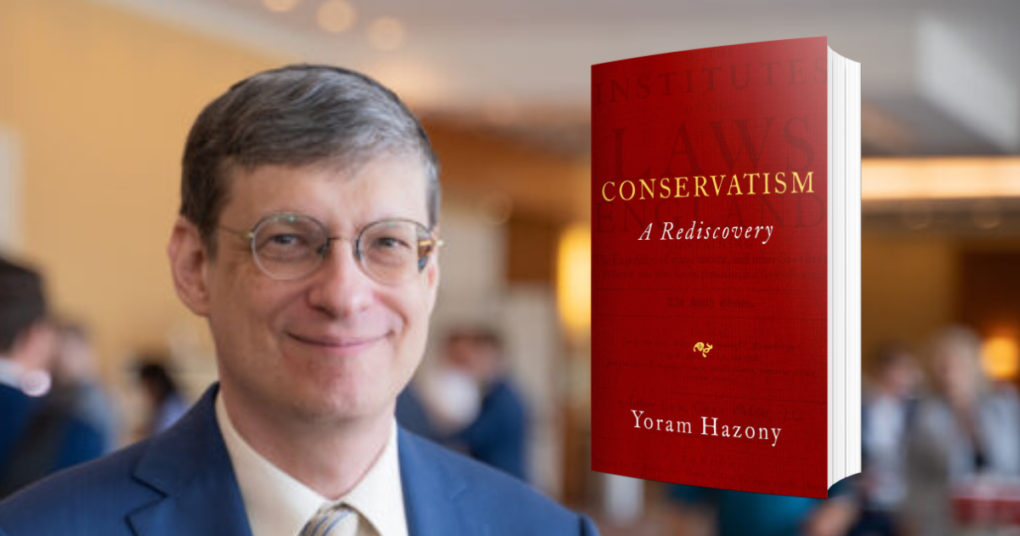

Conservatism: A Rediscovery

Yoram Hazony

Regnery Gateway

2022

256 pages

ISBN: 9781684511099

The Israeli academic and biblical scholar Yoram Hazony has acquired a considerable reputation as one of the main intellectual leaders of the nascent “National Conservatism” movement.

As chairman of the Edmund Burke Foundation he has played a key role in organising NatCon conferences which have attracted various right-leaning figures (including populist nationalists and more traditionalist social conservatives) who are united in their dissatisfaction with the main centre-right parties.

Hazony’s new book, Conservatism: A Rediscovery, provides a thorough and thought-provoking overview of what he sees as the failings of the right-of-centre political establishment in the post-war era.

Setting out his stall early on, Hazony claims that in this time period Enlightenment liberalism became the new framework in which political life was conducted.

He further argues that this “liberal democracy” – which went hand-in-hand with a social revolution that weakened national, religious and familial ties – represented a new system divorced from the classic Anglo-American political tradition.

Cultural upheavals and the rise of the “Woke” movements (which Hazony views as an updated variant of Marxism) have put the kibosh on talk of an “End of History,” and this means that conservatives must reconsider what they believe in.

Hazony defines political conservatism as “a political standpoint that regards the recovery, restoration, elaboration and repair of national and religious traditions as the key to maintaining a nation and strengthening it through time,” while adding that the crucial distinction between it and either liberalism or Marxism is that conservatism is not “a universal theory, which claims to prescribe the true politics for every nation, at every time and place in history.”

His key criticisms of political conservatives in recent decades relates to their failure to conserve the ideas and institutions on which modern Britain and America were built, and he also takes aim at their alleged confusion as to the difference between conservatism and Enlightenment (or “classical”) liberalism.

Structurally, the book is divided into four parts: history, philosophy, current affairs and personal – with this final section dealing how Hazony and his wife came out of broken homes to rediscover the religious traditions of Orthodox Judaism.

Having grown up in the United States, Hazony focuses strongly on the historical development of that country’s politics, which owe much to the parliamentary tradition which had developed in Britain centuries before the American colonists declared independence.

Included among what the author sees as the key principles of Anglo-American conservatism are various historical traditions, the nation state, the importance of religion, limitations on executive power and individual freedoms.

Yet there was never uniformity among key historical figures about many of these matters. One of the most interesting elements of Hazony’s account is his examination of the sharp divisions between the Federalists and Jeffersonians in the republic’s early days.

Federalists took a conservative line on a range of issues, including attitudes towards the French Revolution, immigration and the role of religion in society.

While the Federalist Party eventually declined, their insistence on the need for a strong, unified and coherent nation was to have a lasting impact, just as Thomas Jefferson’s animosity towards religion would lead to the creation of a “wall of separation between church and state” which would harden considerably in the twentieth century.

Yoram Hazony first came to the attention of many readers after writing The Virtue of Nationalism, and the importance of the national community is a recurring theme here, going back to when the fifteenth century theorist Sir John Fortescue recognised that though the English constitutional system was a superior model, it would probably not serve other nations so well.

As the father of philosophical conservatism, Edmund Burke’s description of England’s constitution as being born of the nation’s long experience (“It is made by the peculiar circumstances, occasions, tempers, dispositions, and moral, civil and social habitudes of the people, which disclose themselves only in a long space of time”) is a quote particularly well-chosen.

Less wise is the author’s attempt to portray the brutal and radically unconservative Tudor reformation as “the first modern movement for national independence,” while his description of Elizabeth I “tolerating Catholics…as long as they remained discreet in their practices” suggests that his knowledge of sixteenth century English history is rather limited.

Hazony is far more convincing when he sticks to more familiar ground. One of the key weaknesses which he detects within political liberalism is its blindness to the importance of the nation state, and he sees this limitation as explaining why Western elites cannot recognise why foreign interventionism has failed so miserably in recent times.

In the same way that liberals seek to impose what they see as universalist norms abroad, they are also prone to making needless and often counterproductive changes at home: “[F]oolish rulers are moved by ideology and arrogance, or by an eagerness to make a name for themselves that will be remembered in place of those who came before them, to create everything they touch anew.”

Surveying the recent history of Anglo-American conservatism and the obvious difficulties since the Reagan/Thatcher era, Hazony lays much of the blame on the policy of “fusionism,” whereby American conservatives such as William F. Buckley forged a strong alliance with right liberals and libertarians to combat Communism abroad and economic statism at home..

As well as contributing to confusion as to the difference between conservatism and liberalism, Hazony maintains that this led to a “dogmatic rejection of government” while also preventing people from recognising the need for restraints on individual freedoms.

Tradition – which for Hazony is heavily rooted in religion and Scripture – represents the unifying strand which ties together so much of his argument, just as it unifies whole societies. “[T]he enterprise of seeking truth is not one that the individual pursues by his own powers alone. Tradition is the instrument by means of which human societies pursue truth over time,” he observes.

A religious reader (Hazony is consistent in his attitude towards church-state relations, endorsing a strong role for Christianity in the public life of majority Christian societies) will likely agree with his denunciation of key US Supreme Court decisions in the mid-twentieth century which banned organised prayer and Bible reading in America’s public schools, and eased access to abortion and pornography.

Though he is surely correct about the importance of a religious underpinning in ensuring a stable society, at times he appears to overstate the importance of government action in driving a process of secularisation. After all, the de-Christianisation of the public square has tended to occur as a result of society’s widespread secularisation, not as a prelude to it.

Israel is that rare example of a country which has grown more religious recently, but the unique circumstances of its difficult existence foster this closer link between the spiritual and national identities of Jewish Israelis, just as the natural fecundity of the devout minority tilts the scale in their favour.

It is doubtful that many lessons from Hazony’s homeland can be applied to other societies, but he does a good job in laying out a basic and workable manifesto for “conservative democracy,” including: a clearer emphasis on national identity; greater openness to religion in public life; a stronger role for parents in education; more scepticism about the concentration of power among big business; immigration policies focused on national cohesion; and a non-interventionist foreign policy.

Countries such as Poland and Hungary already have democratically-elected governments who more or less subscribe to this, and nations like Italy have popular parties of a similar mindset.

Britain’s Tory Party remains more socially liberal, but it has increasingly emphasised the importance of sovereignty and secure borders; while in the United States, large sections of the Republican Party (like Florida’s Governor Ron DeSantis or the Ohio Senate candidate JD Vance) would happily identify with Hazony’s vision.

Clearly, his fellow travellers are growing in strength. For those pondering where this process may lead, Conservatism: A Rediscovery would be an excellent place to begin.

About the Author: James Bradshaw

James Bradshaw works for an international consulting firm based in Dublin, and has a background in journalism and public policy. Outside of work, he writes for a number of publications, on topics including politics, history, culture, film and literature. You can visit his blog at: www.jamesbradshawblog.com