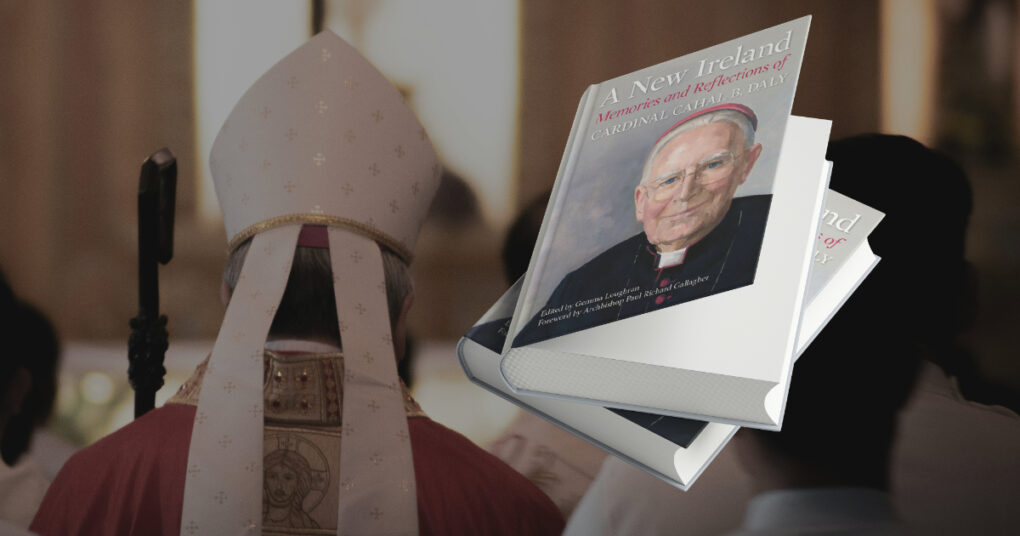

A New Ireland: Memories and Reflections of Cardinal Cahal B. Daly

Gemma Loughran (ed.)

Veritas

2023

167 pages

ISBN: 9781800970632

This book gathers together selected homilies and writings of Cardinal Cahal Daly, a highly respected Catholic leader in late twentieth century Ireland. From Loughguile in the beautiful Glens of Antrim, Cahal Daly was born in 1917 and ordained in Maynooth in 1941. He lectured in scholastic philosophy at Queen’s University, Belfast and served as a theological advisor at the Second Vatican Council. He was bishop of Ardagh and Clonmacnois from 1967 to 1982 and served both as Bishop of Down and Connor (1982-’90) and Archbishop of Armagh (1990-’96) during critical years of the Northern conflict. He died in 2009.

Much has changed in the years since the Cardinal retired, for example, the impact of secularisation North and South, the rise of Sinn Féin and the eclipse of the SDLP, the vote for Brexit in 2016 and its ongoing implications across the island of Ireland.

While major changes have occurred, the history of the Cardinal’s period remains important and this book is a useful reminder, for example, of the Church’s firm opposition to the “armed struggle” of the IRA during the very difficult years of the Troubles.

The Cardinal was a fearless opponent of that “armed struggle” and of loyalist killings in the name of Protestantism, but he also highlighted “the correlation of violence with deprivation” and underlined the need for “rigorous review” of the actions of the security forces. He emphasised the legitimate civil and political rights and aspirations of the two historic traditions in Northern Ireland and the importance of building a culture of dialogue.

Even today, decades later, one cannot read without emotion Bishop Daly’s homilies at funerals like that of Mary Travers, a young teacher who was shot dead by the IRA in April 1984 while leaving Mass in Belfast along with her father Tom, a resident magistrate and thus an IRA target, who was seriously injured in the same incident. The Bishop requested people to reflect on the true nature of an “armed struggle” that shot dead, at point-blank range, a young woman like Mary Travers. Similar homilies, given at the funerals of victims of sectarian murders by loyalist groups, also feature here.

A United Ireland, Daly argued, was a legitimate and noble ideal but “the people of this island have repudiated physical force or coercion as a means to attain it”. Northern Ireland’s political problem, he maintained, was that of “giving political expression to two equally valid loyalties”. Irish Government involvement in Northern Ireland was not “foreign interference” but a recognition of the reality of the Irishness of hundreds of thousands of citizens of Northern Ireland. On the other hand, the real “British presence” in Northern Ireland was “the hundreds of thousands of people who live here, who belong here, and who would still be a British presence in Ireland if the British administration were to withdraw next week”. Irish Nationalists, he argued, “no longer see Irish unity as absorption of a Unionist minority into a united Ireland by virtue of an all-island Nationalist majority…. The Irish majority neither wishes nor could absorb into itself an unreconciled, unwilling and recalcitrant Unionist community.” One wonders, however, if this argument is as well understood today as it was when Cardinal Daly made it in 2001?

It is also good to be reminded here of the Cardinal’s lifelong commitment to ecumenism. He came from a “mixed” area in County Antrim, had close Protestant friends and argued that Church leaders must try to speak across the barriers dividing the two communities. At his installation ceremony in Armagh in 1990, he also spoke powerfully about the need for dialogue with Catholics who were estranged from the Church: “A bishop, as a pastor who should take the Good Shepherd as his model, must go out to them too, he must offer dialogue to them too.”

The Cardinal’s comments on Catholic education also remain of interest today. He was a strong defender of Catholic schools and maintained that where there are no such schools, “secularism spreads very rapidly”. He saw Catholic schools as a strong factor for stability and normality during the hugely stressful years of the Northern conflict, particularly in deprived areas, while arguing that it was important to promote an ecumenical spirit in the formation of Catholic pupils. The Cardinal was also a strong defender of the teaching profession and of its critical social role. He contended that academic success must not be the sole or even the main criterion in our evaluation of school success and praised the dedication which school staff showed towards less academically gifted students.

This book also highlights the importance of Catholic social thought. Daly had a strong interest in the social teaching of the Catholic Church and its implications, and co-founded the journal and priestly society Christus Rex in the 1940s to study those implications and to work for social justice. There are passages here dealing with poverty and unemployment, housing, the arms trade and the preferential option for the poor. He had a strong ecological awareness and wrote a book, The Minding of Planet Earth in 2004, a decade before Laudato Si and was ahead of this time in this area.

This book provides an excellent overview of the Cardinal’s thought but is reasonably short and necessarily selective. One could make a case for the inclusion of other material, for example, Daly’s wide-ranging address on “Christians and the Media” to the Catholic World Congress of the Press in Dublin in October, 1983, in which he critiqued Irish media coverage of the 1983 pro-life amendment campaign and advocated critical engagement with the media.

More coverage of the Cardinal’s lifelong interest in French Catholicism might also have been of interest. The topic merits an entire chapter in his fascinating memoir, Steps on my Pilgrim Journey (Veritas, 1998), which could usefully be read in conjunction with this book. In his memoir, he recalled an important year spent studying in the 1950s in Paris at the Institut Catholique and the Sorbonne. He encountered there both sources of liturgical renewal and the cultural changes facing the Church in France, some years before they fully emerged in Ireland: “I reached the conviction that the same changes would affect Irish society before too long and would consequently confront the Church in Ireland and that French pastoral experience would be illuminating for us.”

His memoir also reflects on the great “wound” of the Church in his time as bishop, “the occurrence of sexual abuse of children, particularly when perpetrated by priests or religious brothers”, which he characterised as a “detestable crime”.

This book includes an illuminating Foreword by Archbishop Paul Richard Gallagher from the Holy See’s Secretariat of State and helpful notes and comments from the editor, Gemma Loughran, a former student of the Cardinal, who has selected these texts.

About the Author: Tim O'Sullivan

Tim O’Sullivan taught healthcare policy at third level in Ireland and has degrees in History and French and a PhD in social policy from University College Dublin.