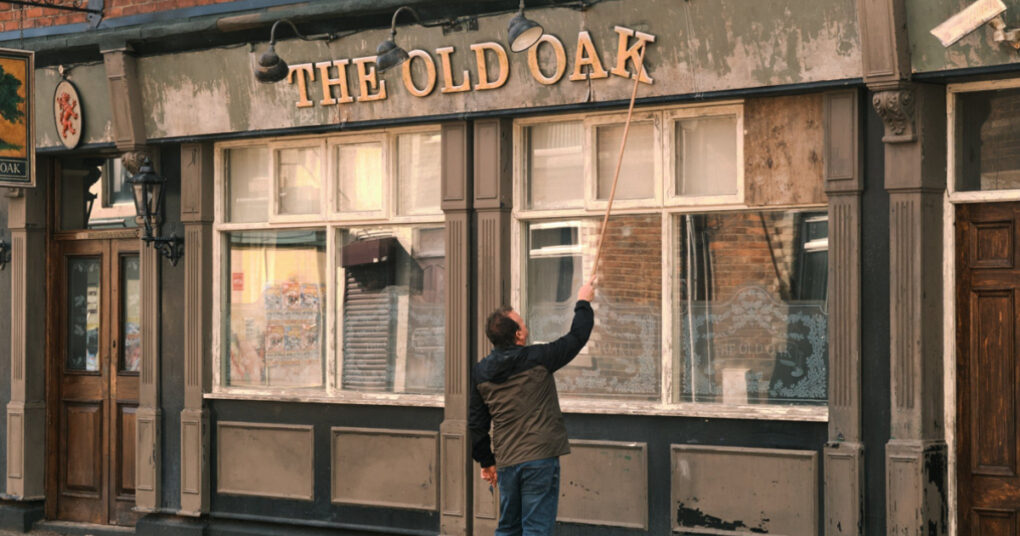

In a poor little town in the north of England a group of Syrian refugees who have fled the war arrive. They are not well received by some of the inhabitants, but others are friendly. TJ Ballantyne, a sixty-year-old who runs an old pub, The Old Oak, is one of the friendly ones. He does not hesitate to help young Yara to repair her camera, which had been broken by a violent ruffian. Little by little, TJ and Yara hit it off, share time and memories. It is a friendship that is frowned upon by a few regulars of the pub – TJ’s colleagues since childhood.

At eighty-seven years old, Ken Loach delivers one of the best films in his extensive repertoire. In what has been announced as his last work behind the cameras, the British director maintains his personal seal, an unmistakable social commitment, but in The Old Oak he leaves aside practically any dialogue that might sound like political ideology and focuses on the issue that underlies all his films: solidarity and social justice, without flags or banners. The result is a beautiful swan song, a moving and profoundly human story about coexistence, integration and the need to give ourselves to others so that our heart can keep beating and not be crushed by despair in the face of life’s difficulties. The Old Oak – what a beautifully metaphorical title – is one of those films that help us continue believing in our fellow human beings.

And how well Loach knows how to tell a story! It is wonderful to witness the buoyant and natural rapprochement between TJ and Yara and how, little by little, the life of both is revealed to us, always through small facts and details brought up in a natural way that enriches them, brings them closer to the viewer and to the other characters. In addition to the painful situation of the refugees, who have lost everything, there is also the insecure life of the inhabitants of the village. We observe their racist reactions, their hard hearts, their attitudes that force one, in the end, to take sides: to believe again that it is possible to live together and share (furniture, toys, accoutrements, food). It is solidarity, not charity, says TJ; it is about distributing what you have, about being a real community. These are generous attitudes that can open paths to what is unspoken, to feel again the sonorous and sacred silence of a cathedral, to discover the miracles capable of saving us from despair in the face of the umpteenth failure. We must never lose hope, shouts Loach in his cinematic testament. The Old Oak of great ideals, though weathered and battered, must stand.

Moreover, there is a great narrative fluidity in The Old Oak. No shot of Loach stops making sense; he doesn’t shoot on the spur of the moment, but goes straight to the point, and shows a superb effort in polishing his visual storytelling, with a script written as always with a wise hand by his perennial collaborator, Paul Laverty. More so than in his other films, here each scene fits together perfectly and adds depth to the content. For the purists, perhaps the only drawback is some repetition. The casting of the actors works perfectly, especially with a very convincing and restrained Dave Turner (TJ Ballantyne) and Ebla Mari (Yara).

About the Author: Pablo de Santiago

This film review originally appeared on https://decine21.com/peliculas/the-old-oak-46424 and is translated by Rev. Charles Connolly and reprinted with permission.