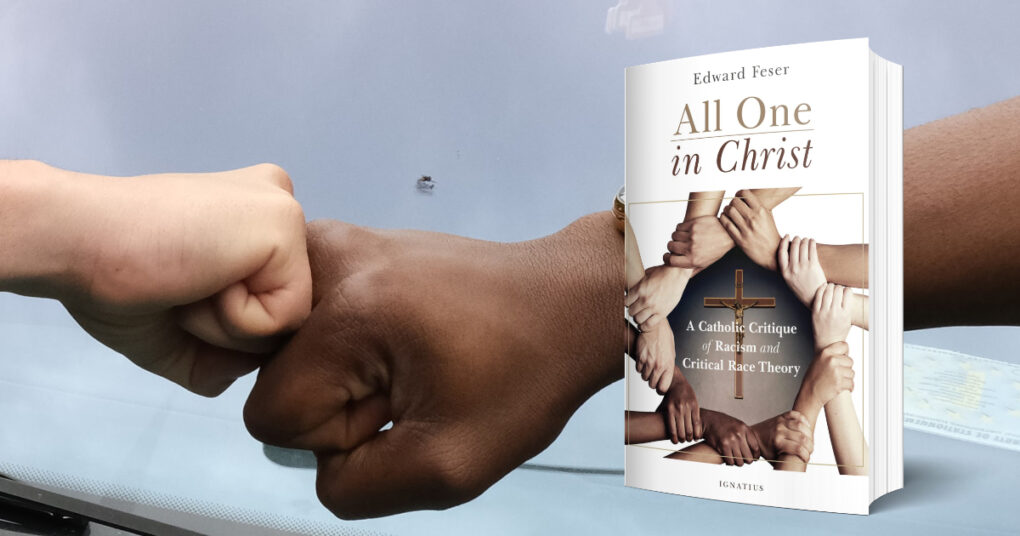

All One in Christ: A Catholic Critique of Racism and Critical Race Theory

Edward Feser

Ignatius Press

163 pages

ISBN: 978-1621645801

Ed Feser, blogger and philosophy teacher, “has the rare and enviable gift of making philosophical argument compulsively readable” according to his colleague Sir Anthony Kenny. He does not disappoint in this slim volume, dealing with the history of Catholic teaching against racism, her teaching on patriotism and immigration, a philosophical look at Critical Race Theory and finally a critique from a Catholic point of view.

Catholicism and racism

He points to a longstanding Catholic dialogue with racism, especially the papal response to the conquest of America: Pope Paul III, in Sublimis Deus (1537) pointed out that the Lord’s command to “teach all nations” means they are all capable of receiving the doctrines of faith; It would be “satanic” to treat them as if they were mere brute beasts. Theologians like Vitoria and Las Casas all dealt with the issue and objections: that Indians were sinners and infidels, that they lacked rationality. They referred to the brotherhood of humanity on Christian and natural law grounds. This approach becomes standard in Scholastic thought. Isolated Catholic thinkers did defend racism or slavery; but the Church never did. She excommunicated those in Brazil who still disobeyed the prohibitions against slavery, and Benedict XIV in 1741, Gregory XVI in 1839, Blessed Pius IX in 1866 and Leo XIII formed a continuous teaching in this regard, long before Vatican II’s clear statements on racism, slavery and discrimination.

The rights and duties of nations and immigrants

Patriotism, for Catholics, is a virtue. It is not racist to be concerned about national identity and/or immigration. Nation and native land are permanent realities. This can go too far of course, and Pope John XXIII in Pacem in Terris spoke of the relationship between immigrants and host nations. There is a two-way duty here, according to Pope Francis: the first thing is for each county to try to better economic and social conditions at home so that people are not forced to emigrate. If immigration is too freely permitted, you end up with ghettos and with oikophobia and people not integrating.

Feser claims that to object to patriotic concerns about national identity because they are sometimes used as a cover for hostility to foreigners is like objecting to romantic love on the grounds that it has sometimes led a jealous lover to murder a rival. The rise of populist and anti-globalist movements in Europe and the United States show that if we don’t adhere to the Church’s moderate teaching, the need to be patriotic may be satisfied in an unhealthy way. The Church’s teaching here is not a concession to nationalism; it is a corrective to it.

What is Critical Race Theory?

He then turns to Critical Race Theory (CRT). Texts such as Robin DiAngelo’s White Fragility and Ibram X. Kendi’s How to be an Antiracist have popularised it in recent years. For Feser, CRT actually promotes a new form of racism. For these thinkers, racism permeates everything. It is the ordinary way society does business. No aspect of society is outside of the forces of racism and by this they don’t mean the Ku Klux Klan: even (especially) liberal and progressive persons are likely to be unconsciously racist. “Colour blindness” language in particular is a mask to hide racism for “the heartbeat of racism is denial”.

The malign source of this is “whiteness”. Antiblackness is foundational to our very identities as white people. This bias is mostly unconscious, so the only remedy is “anti-racist discrimination” and “racial discrimination is not inherently racist”, according to CRT. Liberalism is not good enough, or “step by step progress”. There is no such thing as a “non-racist” neutrality; one is either racist or “anti-racist”. Black people, in particular, are encouraged not to see themselves as “persons”, but as “black persons”. The push for a race-neutral society is the most threatening racist movement, for it is not a matter of changing minds but of power.

Logical fallacies of CRT

Feser has fun pointing out the logical problems with Critical Race Theory. It’s a philosophical position, but an illogical and overreaching one. He lists the logical fallacies which it commits: arguments ad hominem (“of course you’d say that” forgetting to check whether what you said was true or not); poisoning the wells – “why should we believe you?”; genetic fallacy – labelling your opponent so you don’t need to examine his argument; abuse; begging the question – simply assuming your theory is true; special pleading; hermeneutics of suspicion (which should also affect CRT thinking itself!); generalisation; subjectivism and a long etc. Also, it’s unfalsifiable. Whatever you think, if you are a white person, it just proves that you are racist! Heads I win, tails you lose. Feser concludes that if you take away the logically flawed arguments, there is not much else to be found here.

Sociology

But how about sociological evidence? CRT treats all disparities as if they were coterminous with “white supremacy”. This does not stand up to empirical scrutiny. E.g. Asian-Americans perform better than whites; and black-owned banks turn down black mortgage applicants at a greater rate than whites. Is this racism? No one would ever suggest it. For Feser, there has never been proportional representation between groups, and this cannot have been racist. Minority groupings regularly outperform majorities. There are many factors involved: median age; geography; history; culture; immigrants who bring their talents, such as the German beer industry in the USA or Jewish clothing industry in the USA and Argentina.

Cultural values in Africa are not as favourable to business and wealth accumulation as we find, say in European capitalism. This has advantages and disadvantages. Colonialism is a favourite target of CRT but it has been shown to cut both ways: Hong Kong and Singapore are now thriving, but other former colonies destroyed or neglected the infrastructure left by the departing colonisers. Family strength and cohesion is a factor behind success.

CBT or CRT?

There is very little sociological evidence for the supposed microaggressions. Cognitive Behavioural Therapy helps people get beyond the victimhood and paranoia which CRT can encourage. Feser also points to the well-documented improvement in attitudes to racial issues in the USA in the last forty years while, under the influence of CRT, many now believe that things have got worse.

Catholicism and CRT

Kendi pits liberation theology against “saviour theology” (orthodox Christianity, that is) and reduces Jesus Christ to a political figure, airbrushing his constant theme of forgiveness. The Catholic Church has always condemned the thesis that rich and poor, black and white, etc., are inherently hostile to each other. Neither is she impressed with the goal of equalising everyone. There are differences of ability and of outcomes. Cultures differ too, and some are more objectively good and true to humanity than others. So radical egalitarianism is off the menu. So too is the remedy that CRT proposes for these ills which is always about power, rejecting the moderation of the traditional civil rights movement, etc. Racist discrimination can cut both ways, according to The Church and Racism, a Vatican document from the 1980s. Mercy is the true face of love, for Pope Francis. So, let’s try rational discourse and charity, says Feser, rather than cancel culture and the hermeneutics of suspicion.

An informative, well organised and bracing read which can help to navigate these choppy waters.

About the Author: Patrick Gorevan

Rev. Patrick Gorevan is a priest of the Opus Dei Prelature. He lectures in philosophy in St Patrick’s College Maynooth and is academic tutor at Maryvale Institute. He has written on the early phenomenological movement, virtue ethics and the role of emotion in moral action.