Last month’s twenty-fifty anniversary of the Belfast/Good Friday Agreement (GFA) of April 1998 provided much food for thought on what has been achieved to date and on future prospects. This article draws and reflects on an excellent Irish Catholic special edition on the GFA at 25 (April 13, 2023).

Thinking back on the GFA, one’s overwhelming sense is of gratitude for the lives saved because of the vastly improved security situation since 1998. There is gratitude too that the younger generation have not had to experience the same trauma as their parents.

As someone brought up in a border county in the Republic, I was very much sheltered from the day-to-day conflict but nevertheless had indirect experience of it through friends in the North and direct experience of the tense security situation when I crossed the border. I vividly remember four and a half long hours spent at the border crossing in Aughnacloy, Co Tyrone during a very tense time in the 1970s, when each car was receiving minute examination from the British Army.

I was also struck by the experience of friends from the North, who used to tell me that tension drained away from their bodies when they arrived at the border with Donegal and that they did not realise until those moments how tense they had previously been.

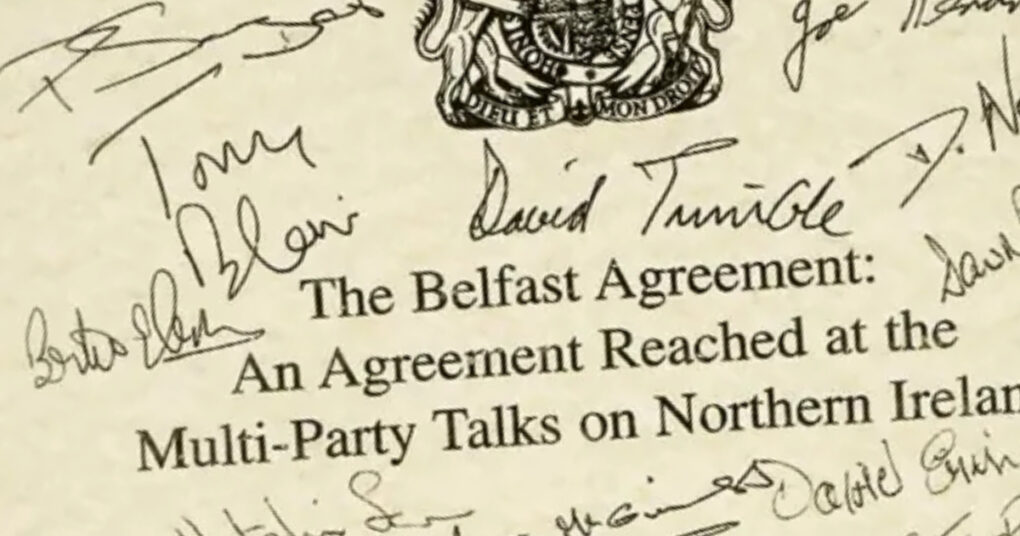

Twenty-five years on, I feel gratitude for the contribution of the peacemakers like John Hume, Gerry Adams and David Trimble or Fr Alec Reid and Fr Gerry Reynolds. The Churches are not always given the credit they deserve for their contribution to peace-making and reconciliation during the darkest days of the Troubles and arguably for preventing a drift towards a full civil war.

Writing in the Irish Catholic, Professor Francis Campbell praised that contribution of the Churches and mentioned the priests and ministers who called for forgiveness, not revenge, at the time of tragic funerals as well as the persistent peace-making work of people like Fr Reid, Rev Harold Good, Cardinal Cathal Daly, Bishop James Mehaffey and Bishop Edward Daly. Campbell also quoted the prophetic words of Pope St John Paul in Drogheda in 1979: “On my knees, I beg you to turn away from the path of violence and return to the ways of peace.” The Pope’s words were not heeded at the time but surely planted strong seeds for the future.

Dr Martin Mansergh, a key actor in the peace process, maintained that the GFA was a landmark in Irish history and an agent of progress, bringing all the people of Ireland closer to each other. There are, he argued, many gains from the GFA needing to be protected, “above all, the freedom, security and confidence given to people by peace”.

Baroness Nuala O’Loan suggested that it is not enough to look back with pride, but that it is also necessary to make Northern Ireland today a place of good Government and sensible decision-making and thus to give effect to the aspirations of those who toiled to achieve the GFA.

Looking forward, there is legitimate concern about the polarised attitudes of today. Serious convulsions have been caused by Brexit and the Northern Ireland Protocol, and the Assembly and Executive are not functioning at present because of the withdrawal of the DUP. It is important for us in the South to take account of Unionist perspectives, including the strength of Unionist opinion on the protocol, even if it has arisen as a result of Brexit. The Belfast Newsletter, a Unionist paper, editorialised on April 13 about the “disastrous situation” of a “major internal trade barrier between NI and Great Britain”. Nevertheless, one could ask if the DUP has weighed sufficiently in the balance the damage its continued absence could do to the hard-earned cross-community structures.

The GFA recognised the legitimacy of any choice made by the people of Northern Ireland – whether to continue as part of the UK or to become part of a united Ireland (the principle of self-determination). Campaigning for a united Ireland is thus fully legitimate and some sort of federal structure might well emerge at some point in the future.

However, the increasingly militant tone in current nationalist and Republican commentary, with its somewhat dismissive attitude to the Unionists, and its focus on Northern Ireland as a “failed entity” or “statelet”, do not seem helpful. Some current articles by Republican activists read as if they could have been written thirty years ago – and as if a major international, cross-community agreement had not been achieved in the meantime! As Dr Mansergh argued, it is pointless to press for an early border poll, only for it to be defeated, when this will only heighten tensions.

Many ordinary citizens might argue that the focus at present should be on making the current structures work for the good of all. There is also room for ecumenical cooperation between Christians on both faith and social questions, such as pro-life issues north and south. In the Irish Catholic, Bishop Donal McKeown of Derry wrote that a new division has arisen, both North and South, – between those who want to retain space for the Christian worldview in education and those who would seek to banish anything other than an intolerant secular philosophy from the public sphere.

Archbishop Eamon Martin highlighted the importance of reconciliation and the need to build a more reconciled community in a context where significant sectarian polarisation still exists. Bishop McKeown maintained that the key issue we face in Ireland is not so much to do with political structures now or in the future, but rather with the sort of society we believe is possible for the people of this island. His hope was for a new generation of faith-filled peacemakers.

About the Author: Tim O'Sullivan

Tim O’Sullivan has degrees in history and social policy from UCD and taught healthcare policy at third level.