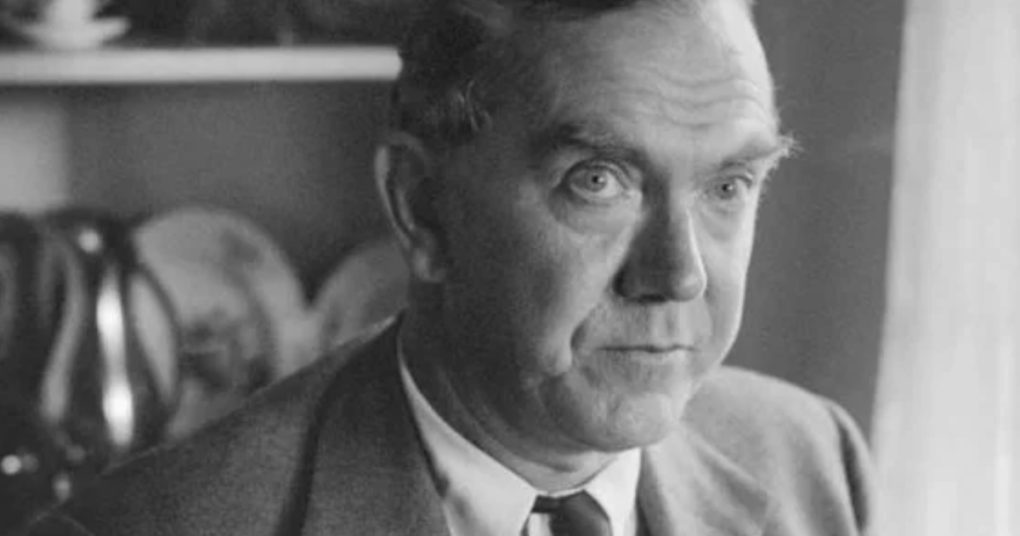

Graham Greene was a complicated man – and his novels were no less complicated. He clearly did not shy away from leaving people with problems to think about – and we can only thank him for that. His life was also somewhat complicated. He was a convert, his conversion initially motivated by his love for a devout Catholic woman. He was, however, neither a faithful husband nor, after a time and for many years, a faithful Catholic. But he died reconciled to the faith, the Church and its sacraments.

He was never hostile to the faith and once wrote to a cardinal, “I wish to emphasise that, throughout my life as a Catholic, I have never ceased to feel deep sentiments of personal attachment to the Vicar of Christ, fostered in particular by admiration for the wisdom with which the Holy Father has constantly guided God’s Church. I have always been vividly impressed by the high spirituality which characterizes the Government of Pius XII. Your Eminence knows that I had the honour of a private audience during the holy year 1950. I shall retain my impression of it until my last breath.”

His novels reflected much of the turmoil of his own journey in the faith and were, still are, valued by many for the negative capability they have to tell the truth about the human condition and mankind’s struggle to be good in the face of the evils assailing him from without and from within.

One prominent churchman made this assessment of his work, writing that “his harsh and acerbic art touches the hearts of the least receptive and reminds them, however gloomy they may be, of the awe-inspiring presence of God and the poisonous bite of sin. He addresses those who are most distant and hostile – those whom we will never reach.”

The Power and the Glory, probably Greene’s most famous novel, was the context in which those remarks were made. It was published in 1940 but did not become controversial in Catholic circles until the 1950s. Prompted by this, the Vatican appointed two consultants to study the book in 1953. Both were critical, deeming it immoral and in the opinion of one, “odd and paradoxical, a true product of the disturbed, confused and audacious character of today’s civilisation.”

The novel is set in the southern-Mexican state of Tabasco, which is governed by a ruthless persecutor of Catholics, Tomas Garrido Canabal. An atheist and a puritan, Canabal detested organised religion and alcohol. The central figure in Greene’s book is an alcoholic priest, who is put to death by Canabal’s police at the end of the novel. Although he anticipates his execution, and knows that he is walking into a trap, he chooses to perform what he sees as his duty and attempts to give the last sacraments to a fatally wounded criminal. The priest puts the chance of saving another man’s soul ahead of his own survival. Is he a martyr? Or is he being justly punished for his lax and scandalous life? The moral and theology of The Power and the Glory are ambiguous. Unfortunately ambiguity – which is at the heart of much of the literature we treasure – is something to which many of a censorious and too literal – as opposed to literary – turn of mind are both deaf and blind.

But not so, Cardinal Giovanni Batista Montini, pro-secretary of state at the Vatican, and later to be elected Pope Paul VI in 1963. Montini, hearing of the controversy and the drift which the Vatican officials were taking, wrote to the secretary of the Index of Forbidden Books (disbanded in 1966) in the Holy Office that the book was “a work of singular literary value. I see that it is judged a sad book. I have no objection to make to the just observations [of this work]. But it seems to me that, in such a judgment, there is lacking a sense of the work’s fundamental merits. They lie, fundamentally, in its high quality of vindication, by revealing a heroic fidelity to his own ministry within the innermost soul of a priest who is in many respects reprehensible.”

He suggested to the Holy Office that “it would be well to have the book assessed by another consultant before passing a negative judgement on it, not least because author and book are known worldwide.” Monsignor De Luca – whom Montini suggested – concurred with him about the book’s literary quality and morality:

“Graham Greene and Evelyn Waugh according to expert opinion, are to be considered the two major living novelists: being Catholic they do credit to Rome’s faith, and they do credit to it in a country that is of Protestant civilization and culture. How can Rome be gruff and cruel? They are the successors of Chesterton and Belloc and, like them, rather than attempting to convert the small fry, strive to influence superior intelligences and the spirit of the age in a manner favourable to Catholicism.”

“This,” De Luca went on, “is not a matter of heresy or even a scandal; it has nothing to do with theologians or depraved persons. We are dealing with great writers, who are often naive and obstinate like children, in states of mind that are, from time to time, not inclined to praise but gloomy, not exultant but insistent…. To condemn or even to deplore them would … demonstrate … that our judgement is light-weight, undermining significantly the authority of the clergy, which is regarded – rightly – as unlettered bond-slaves to puerile literature in bad taste.

In the case of Graham Greene, his harsh and acerbic art touches the hearts of the least receptive and reminds them, however gloomy they may be, of the awe-inspiring presence of God and the poisonous bite of sin. He addresses those who are most distant and hostile – those whom we will never reach.”

Greene’s justification for what he had written was that the aim of the book was to contrast the power of the sacraments and the indestructibility of the Church on the one hand with, on the other, the merely temporal power of an essentially Communist state – revolutionary Mexico in the early twentieth century.

In his introduction to a later edition of The Power and the Glory, Greene gives a telling personal account of this affair in which he wondered if there was any other authority in the world which would have treated a stubborn resister as gently as he was treated by the Catholic Church when he dug in his heels. He wrote:

“The Archbishop of Westminster read me a letter from the Holy Office condemning my novel because it was ‘paradoxical’ and ‘dealt with extraordinary circumstances’. The price of liberty, even within a Church, is eternal vigilance, but I wonder whether any of the totalitarian states … would have treated me as gently when I refused to revise the book on the casuistical ground that the copyright was in the hands of my publishers. There was no public condemnation, and the affair was allowed to drop into that peaceful oblivion which the Church wisely reserves for unimportant issues.”

In a long article on this affair in The Atlantic, in 2001, Peter Godman takes the story on into the 1960s. In July 1965 Greene had an audience with Montini, now Pope Paul VI. “He told the Pope that The Power and the Glory had been condemned by the Holy Office. According to Greene, the Pope asked, ‘Who condemned it?’ Greene replied, ‘Cardinal Pizzardo.’ Paul VI repeated the name with a wry smile and added, ‘Mr. Greene, some parts of your book are certain to offend some Catholics, but you should pay no attention to that.’”

Godman commented:

“These sentences have intrigued me ever since I first read them, some years ago, in Greene’s Ways of Escape. The records of censorial investigations undertaken after the death of Leo XIII, in 1903, are in the archives of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, and are not available to be consulted by outside scholars. In February of last year I sought and obtained an audience with the Congregation’s prefect, Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger. To my request that an exception be made to the rules, the reply was one word, uttered without hesitation: ‘Ja.’”

Godman’s explorations of those archives reveal much of the detail of the case and the denouement suggests the same judgment as Greene himself made on the ultimately wise conclusions reached despite the fallible and fumbling manoeuvres of some of the dramatis personae in the comedy.

“The mindset of Rome’s censors”, he says, “was not malevolent. It is difficult, however, to resist the conclusion that it was dim. Defensive about their authority (which they desired to assert even as they doubted its efficacy), and incapable of grasping the conceptual problems posed by Greene’s writing, they could be checked in their course only by intervention from above.” That was Montini’s intervention.

Godman poses the question, why did Montini stand up for Greene? He describes him as “an intellectual whom John XXIII is said to have likened to Hamlet, Montini was alive to the problem of moral ambiguity. He was capable of discerning links between apparent contraries where less perceptive others saw none.”

“Montini was not only a reader of refined literary tastes but also a collector of literary manuscripts. Among them figured the handwritten original of a booklet on Saint Dominic by Georges Bernanos, which ends with the sentence ‘There is only one sadness – not to be a saint.’ Montini treasured that work, echoes of which he cannot have failed to hear in The Power and the Glory. The words ‘He knew now that … there was only one thing that counted – to be a saint’ come at the very end of the penultimate chapter of Greene’s novel.”

Finally, Godman notes, three weeks after Greene had written his letter to Cardinal Pizzardo, the Secretary of State, Cardinal Ottaviano, scrawled on it that Cardinal Griffin had told him that the Holy Office should “understand and excuse” this right-thinking convert. And that is what was done.