Sword of Honour

Evelyn Waugh

Chapman & Hall

1952-1961

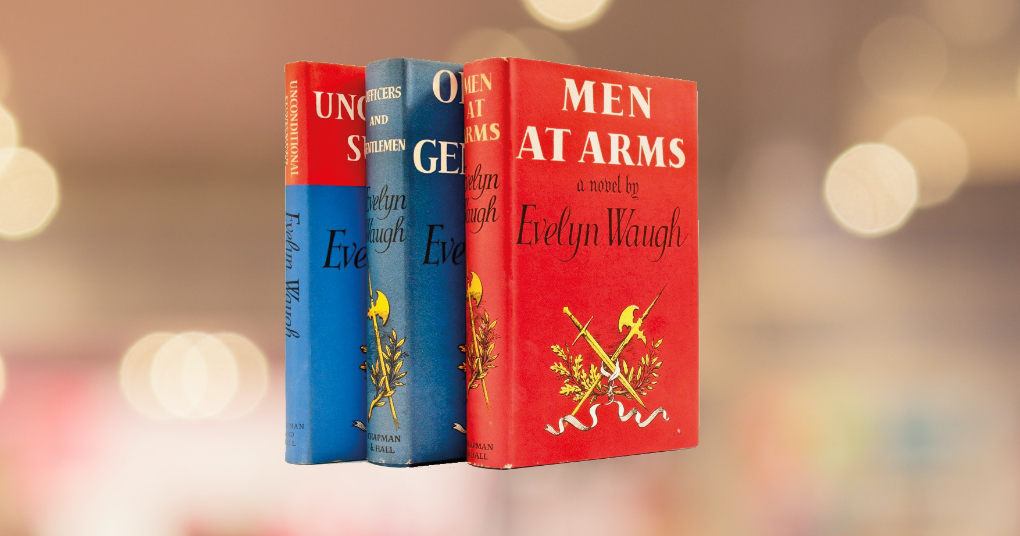

Evelyn Waugh’s Sword of Honour trilogy comprises the three short novels born of the author’s experiences in the Second World War: Men at Arms (published in 1952), Officers and Gentlemen (1955) and Unconditional Surrender (1961). Taken individually, the short novels are an absorbing and entertaining insight into the war, and the small part which Waugh played in it. When read together, Sword of Honour represents the pinnacle of his achievements as a writer, where he provided the deepest insights into religious faith.

For many readers, Brideshead Revisited will always be regarded as Waugh’s masterpiece. There are certainly close parallels between that story and the one told in Sword of Honour. Both works centre around a family belonging to England’s Catholic aristocracy, or as the author put it, those “families which had suffered for their Faith and yet retained a round share of material greatness.”

In each case the ancient recusant line appears to be coming to an end. The protagonist Guy is the only surviving son of the Crouchback family of Broome. He is childless and alone, and at the outset, the financial standing of the family also appears greatly diminished. As with the Flyte family of the Brideshead estate, there appears to be nobody to carry on the name, and the property in Broome is now rented to a convent. Yet just as in the unforgettable conclusion in Brideshead, it is clear that something of far greater permanence will remain long after the Crouchbacks pass into history, for “the sanctuary lamp still burned at Broome as of old.” Another overlapping theme relates to divorce, for it is the abandonment of Guy by his wife Virginia which has brought about this ruination: the last surviving son cannot remarry and so will never produce an heir.

Probably the main reason why Brideshead Revisited is more famous is the 1981 television series starring Jeremy Irons and Anthony Andrews. This outstanding production drew much of its strength from how its producers remained deeply faithful to the novel, keeping divine grace and reconciliation at its heart. There have been attempts to adapt Sword of Honour for the screen, including a 2001 film starring Daniel Craig, but none has done the books justice. The Brideshead series took eleven hours to tell a story contained in 430 or more pages. Sword of Honour is nearly twice as long, and it would require an enormous investment to make three films. In today’s world, it would also be much less likely that film or television producers would remain faithful to the religious message.

Christopher Hitchens once wrote of the theme of lost innocence which bubbled under the surface in Brideshead, whose main characters were too young to have fought in the First World War. Here, the shadow is much darker. Guy’s eldest brother Gervase had been killed in the conflict, and as the next war looms, it is made clear that the German enemy has grown much more vicious. Far from being forced to fight, a listless and detached Guy is at first eager to join a struggle which will allow him to escape his exile in Italy and give his life meaning once more.

The alliance between Nazi Germany and Communist Russia and their combined assault on Catholic Poland clarifies the conflict, so that all of the worst modern political forces could be fought at once by those like Guy who still held to the older values of tradition, honour and Faith. “[S]plendidly, everything had become clear. The enemy was at last plain in view, huge and hateful, all disguise cast off. It was the Modern Age in arms,” Waugh writes.

Before returning to England and commencing his personal crusade, Guy pays his respects to an earlier English knight who died on his way to the Holy Land. He runs his hand along the dead knight’s sword in theatrical fashion, saying: “Sir Roger, pray for me … and for our endangered kingdom.” This high-mindedness quickly recedes. Waugh was a master of satire, and years spent inside the military bureaucracy gave him the material to make these books some of his funniest work.

Aside from his usual sharp-eyed critique of upper-class English life, the close assessment of the officer corps means that the reader is treated to a range of characters which leap off the page: the imposter Trimmer, the professional hero Brigadier Ben Ritchie-Hook and the socially inept Apthorpe, with whom the Brigadier wages a psychological war over a portaloo. Spies abound, and as Guy moves from one front of the struggle to another, he is simultaneously being tracked by military intelligence for fear that he is among their number.

Much of the story is rooted in Waugh’s diverse wartime experiences, first as a Royal Marine, then as a commando and lastly in military liaison work in Nazi-occupied Yugoslavia. The author does not use the character of Guy to exaggerate the scale of his involvement in actual fighting. Guy, in fact, chafes at his inactivity and various misfortunes and reversals prevent the protagonist from playing the part he intended in leading men into battle.

For Waugh himself though, this was only partially true. Guy Crouchback is naturally melancholy – confessing to a priest during the war that he wishes for death – but though a natural solitary, he is a competent officer and is shown to demonstrate kindness towards those under his command.

The naturally bad-tempered and aloof Waugh was a different case entirely. His friend, biographer and fellow officer Christopher Sykes made clear that Captain Waugh was so despised by his men that his comrades feared they would murder him given half a chance. Perhaps Waugh’s own failings as a military man contributed to the broader disillusionment which Guy feels as the nature of the war changed, as Stalin became a British ally and as many Eastern Europeans (including Guy’s fellow Catholics in Yugoslavia) came to understand what Communist occupation would entail. By the end of the struggle, all enthusiasm has vanished, and Guy feels regret for ever having believed that “private honour would be satisfied by war.”

This Catholic imprint makes this a very different type of war novel, in which Britain’s great victory and Nazism’s destruction does not lead to unqualified elation. In it, the elder Mr Crouchback is the very embodiment of the values for which his son has committed to fight. Hearing that his only grandson is missing in action after the evacuation of France, Mr Crouchback writes to Guy that he is sure that Tony would have died bravely with his friends, and that it “is the bona mors for which we pray.”

Scion of an ancient family whose adherence to Catholicism had prevented their village from apostasising, Mr Crouchback becomes a schoolmaster during the war, and regales his young charges with the story of how his martyred namesake had died heroically. Seeing his son’s despondency at how the moral crusade had been tainted, the father remonstrates with him, reminding him of a higher form of justice: “Quantitative judgements don’t apply. If only one soul was saved that is full compensation for any amount of loss of ‘face.’”

The words of the “only entirely good man … he had ever known” come back to Guy again and again, not least when he makes the faithful decision to put duty before pride when his former wife falls pregnant out of wedlock. The strange workings of Providence in perpetuating one family and one Church are foreshadowed early on in a tale which stretches out over the course of a decade.

One day, Sword of Honour may be brought to a broader audience, but even if this never happens it will remain the highest testament to the skills of the greatest novelist of the twentieth century.

About the Author: James Bradshaw

James Bradshaw works for an international consulting firm based in Dublin, and has a background in journalism and public policy. Outside of work, he writes for a number of publications, on topics including politics, history, culture, film and literature.