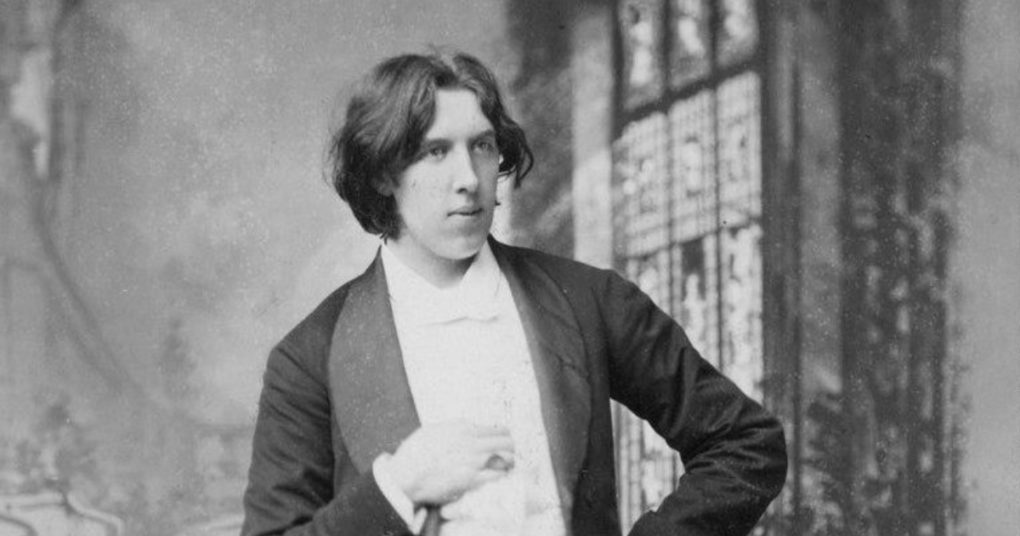

Oscar Wilde came to the sacraments of the Catholic Faith late in his tragic life. But he had, before his conversion, sensed their mystery and reflected on it in his portrayal of the goings-on in the troubled heart of his tragic hero, Dorian Gray. While on his deathbed he may have received only two sacraments from a Catholic priest – confessing his sins and receiving the last rites – his sense of their ineffable significance can be seen ten years earlier in that timeless moral masterpiece, The Picture of Dorian Gray.

The novel’s narrator, in taking us through the furtive meandering of Gray’s journey to destruction tells us that “It was rumoured of him once that he was about to join the Roman Catholic communion; and certainly the Roman ritual had always a great attraction for him. The daily sacrifice, more awful really than all the sacrifices of the antique world, stirred him as much by its superb rejection of the evidence of the senses as by the primitive simplicity of its elements and the eternal pathos of the human tragedy that it sought to symbolise.”

The narrator goes on to tell us that “he loved to kneel down on the cold marble pavement, and watch the priest, in his stiff flowered vestment, slowly and with white hands moving aside the veil of the tabernacle, or raising aloft the jewelled lantern-shaped monstrance with that pallid wafer that at times, one would fain think, is indeed the panis cælestis, the bread of angels, or, robed in the garments of the Passion of Christ, breaking the Host into the chalice, and smiting his breast for his sins.”

Dorian, his narrator tells us, finishing his account of this encounter with the Holy, would, as he passed out of whatever church he was in the habit of visiting, “look with wonder at the black confessionals, and long to sit in the dim shadow of one of them and listen to men and women whispering through the worn grating the true story of their lives.”

A childhood memory which might perhaps be shared by any number of those of us of a certain generation who grew up in Catholic families might be this: the quiet joy and happiness of our parents on hearing that a lapsed friend, neighbour, or even some well known figure – celebrities are a modern phenomenon – had “returned to the sacraments”.

As believing children the hidden depth of that joy was not something we would have fully appreciated, but it was something palpable and indeed infectious. It left us with some sense that in these mysterious seven literal and tangible elements there was something special on which joy and happiness depended.

Those childhood intimations of the awful reality which the sacraments represent, literary representations of that same power reflected on by Oscar Wilde and other writers, all bring home to us the dangers in the version of modernity which now seem to confront us. This version denies this reality, or has such a superficial awareness of it that it is virtually blind to it.

This crisis for our human race is calmly and wonderfully laid before us in all its terrible beauty by Oliver Treanor in a book which he wrote a handful of years ago called Malestrom Of Love (Veritas, 2014). Treanor is an Irish theologian. In introducing his theme – the Eucharist and its pivotal role as the centre around which all the sacraments of Christ revolve and by which the Church lives – he tells us that the gravest danger for the human person and for civilisation is to lose touch with reality. Any version of reality which denies the existence of God is for him, something not only incomprehensible but a terrifying prospect.

He reminds us that in the twentieth century we all saw what happens when pure fantasy replaces “the realism of the good”: two world wars, totalitarianism, political breakdown, social chaos, moral disintegration, exploitation of the helpless, and disregard for human life at its beginning and its end. In sum, he says, it was the century of mass genocide, physical and spiritual, the beginning of civilisation’s descent into suicide.

It was everything which Dorian Gray personified in Wilde’s prophetic novel.

What Treanor is telling us is that our grasp of reality is what is at stake if we lose sight of God, because God is man’s foundational and ultimate reality. “The twentieth century lost sight of God. The Eucharist and the sacraments put us in touch again with him who touches us through them, re-forming our minds and hearts, bringing them back to reality. Given this, the Church is no optional extra for the pious and reverent, not a footnote to social history, some inconsequential aside non-essential to the text. Rather it can be said that without the Church and sacraments, primarily the Eucharist, the world would cease to exist. For they embody the mercy of God which alone sustains the creation in Christ ‘through whom and for whom all things were made and in whom all things hold together’.”

Treanor masterfully explains the entire Christian economy based on the the foundation which the Catholic Church calls the sacramental system. For him it is, in a manner of speaking, “the cipher that breaks the enigma of the cosmos and decodes the meaning of life. In short, it gives God away.” It is, he says, so simple that even a child can see it, yet so profound the mature intelligence cannot fathom it.

But he then comes to the false turning taken by the forces now dominant in modern culture. While he sees in that turning, a search for the very answers which a God-centered worldview offers, he lays bare the fatal flaw in the alternative path they offer to man in his search for truth, meaning and happiness:

“The worldview that underpins post-modernism’s resistance to religious conviction (or grants it grudging tolerance as a social convention) is actually in its own right a response — however inadequate — to those questions at the heart of human existence that find their answer in the Eucharist. Atheistic autonomy, scientific rationalism, false pluralism, so-called liberationism, all have this in common with orthodox faith: they begin with some concept of what meaningfulness is, even if they settle for finding it in no meaning at all other than mere activity. But because God is not their centre and the human person not their end, they lack what the sacraments offer, namely real human progress” (p23).

They are sterile and hopeless because “the object of their search is incomplete even though the search itself emanates from the Completeness that beckons to us all. Hence they look for knowledge but not truth, for expedience but not justice, for productivity but not fellowship, for engagement but not commitment, for absence of ties but not freedom, and for control but not service.”

Treanor takes his reader through the sacraments one by one and does so in a way which makes clearer than anything I have ever read, the unity of the whole, with the Eucharist at its centre. Writing about Matrimony, for example, he describes how (p.133) this sacrament springs from the Eucharist and finds its meaning and strength in returning to the Eucharist as “the sacrament of the purification of Christ’s bride, generated from his crucified side and espoused by his rising to claim her as his own. Gradually, married life takes on the self-sacrificing character of him who is its inspiration and example and the means to attaining love’s highest possibilities. The grace matrimony provides is that of centring on the person of Christ, his passion and resurrection as the foundation of life’s realism and love’s maturity.”

But the true crisis of our time is the loss of the sense we used to have of the value and unfathomable depth of the treasure which faith is, and which the sacraments keep alive in us. This loss is reflected in the scenario recounted by Treanor when he enumerates features of the laxity prevailing today (p.166). These include Catholics who rarely attend Mass but who will routinely receive the Eucharist at weddings and funerals for instance; others, divorced and re-married or co-habiting without matrimony who are Mass-goers, and who will automatically receive on each occasion; others still whose ethical life contravenes the Church’s teaching on abortion, the regulation of birth, fertility treatment, homosexuality, or euthanasia — to name the principal areas of concern — will expect to be given communion as a matter of course as by right.

All this is done oblivious of the fact that the mystery that here stands revealed is an eternal truth that lays bare the mind of God, the real nature of mankind, the meaning of history and the destiny of creation. They are oblivious of all that Christ’s mandate, “Take, eat, this is my body…. Do this…” really intended. They are unaware that “Love one another as I have loved you…” is only truly Christian when it means washing feet in Christo, forgiving enemies in Christo, laying down one’s life for friends in Christo, following “my example”, keeping “my word”. Treanor explains that “it means entering the maelstrom of love to be caught up in the centrifugal force of Christ’s charity towards the world in union with God and in service of men; and then to be constantly drawn back again by that same charity in the centripetal force by which God in Christ is taking the world, as he always intended, into his heart (p.172).

He explains that “what the Eucharist is substantially, the Church is mystically so that it has even been said that the Church is the Eucharist extended, while the Eucharist is the Church condensed.” Both can be called the universal sacrament of salvation and are so by dint of their interrelatedness, the Eucharist generating the Church, the Church making the Eucharist (p.195).

Is not a denial of the teaching of the Church and a refusal to accept its admonitions and moral guidance about the way we live our lives not also a denial of the Eucharist?

Among all the things which Treanor’s rich and revealing exposition of the Church, the Eucharist and the sacraments make very clear, two things stand out. The first is the blind and terrible folly of those who denigrate this sacred and ineffable truth because they confuse the errors and misjudgment of its servants with the holy thing that it is in itself. The second is the need to reaffirm, teach and learn how to love again those things which our forebears appreciated and which are the only secure basis of a moral life and a truly just society. Had Dorian Gray not passed out of that church and had he accepted the grace of conversion which Wilde depicts him walking away from in his weakness, his picture would have been a very different one.

About the Author: Michael Kirke

Michael Kirke is a freelance writer, a regular contributor to Position Papers, and a widely read blogger at Garvan Hill (garvan.wordpress.com). His views can be responded to at mjgkirke@gmail.com.