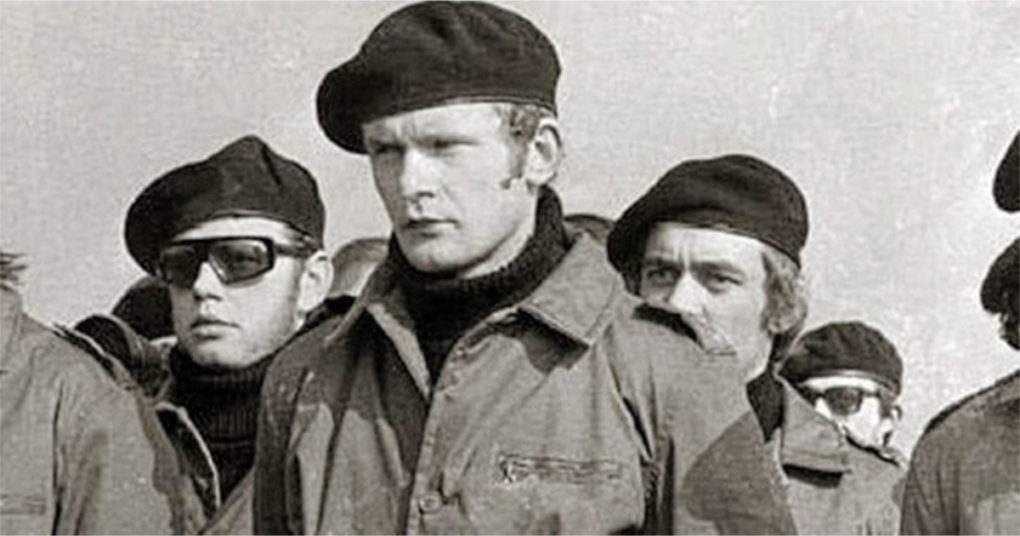

The recent RTÉ documentary, McGuinness, was a triumph for all involved in making it. Written by Harry McGee of The Irish Times, it was a gripping account of the life of one of the most important political figures in modern Irish history. While Gerry Adams has been the undisputed leader of the Republican movement since the 80s, his junior colleague Martin McGuinness was always more compelling.

Unlike Adams, McGuinness was not born into the IRA, and the oversized role which Derry played in the early days of the civil rights movement coupled with the appalling slaughter on Bloody Sunday adds to the sympathy which ordinary people felt towards him.

Overall, the focus of the documentary was admirably balanced. A wide array of leading figures in the Peace Process were featured. Some of the interviewees clearly revered him while others like the DUP’s Gregory Campbell were deeply hostile. Victims of IRA violence were understandably critical about the omission of key details, such as the role which McGuinness allegedly played in luring the Republican informer Frank Hegarty to his death in 1986. The late Bishop of Derry Edward Daly believed McGuinness played a direct role in Hegarty’s murder by encouraging him to return to Derry, and told an Irish government official as much some months after the killing.

The bigger flaw within the documentary related not to the failure to address every IRA atrocity – a mini-series would be needed – but to how it framed the overall narrative of the Troubles. What we saw resembled too closely the revisionist view of the conflict which the wealthiest and most dangerous party in Irish politics constantly propagates.

Their potted history runs as follows:

- In the late 1960s, disenfranchised Irish Catholics living in a bigoted state began a powerful people’s movement for civil rights. (This is true.)

- Faced with no alternative (here the lies begin), a group of Irish revolutionaries – the moral equals of those who founded the Irish State – took the fight to the British Army and RUC.

- After decades of armed struggle, courageous leaders such as Gerry Adams and Martin McGuinness were finally able to bring the British Government to the negotiating table.

- Thanks to their courage, and some minor assistance provided by the previously uncooperative John Hume et al, the newly-created Peace Process ensured that Irish unity could now be achieved by non-violent means.

Sinn Féin have become the most powerful force in Irish politics partially on the back of this narrative. Whenever they are challenged about their blood-soaked past, this is the story they return to. This historical narrative rests on certain building blocks: if one underlying assumption or component of the argument gives way, the whole structure collapses. The most important underlying claim is that a non-violent path towards changing Northern Ireland did not exist before the Good Friday Agreement.

This is an absolute falsehood and must be challenged at every turn.

In 1973, moderate nationalists, moderate unionists and the British and Irish governments signed up to the Sunningdale Agreement which required power-sharing in the North, along with the creation of a 32-county Council of Ireland aimed at promoting peaceful cooperation between North and South.

McGuinness and the IRA rejected this outright. After four years of hellish violence, they still would not give up. Granted, a large segment of the unionist population (such as Ian Paisley) also rejected Sunningdale, and militant loyalism played a key role in collapsing the agreement.

Yet a significant faction of unionists (such as Ian Paisley) also rejected the Good Friday Agreement in 1998. A key difference is that the IRA had halted their campaign before the Good Friday Agreement made it obvious that they were unlikely to resume their offensive. If the IRA had been willing to abandon violence in the 70s, two decades of pointless conflict would have been avoided.

Not for nothing did the late, great Seamus Mallon – a ceaseless critic of the IRA campaign and leadership – call the Good Friday Agreement “Sunningdale for slow learners.” By the late 1990s, the IRA leadership – with Adams and McGuinness at its heart – was willing to accept less than what was on offer at Sunningdale a quarter of a century earlier, provided that hundreds of Provisional IRA members would walk free from jail. And provided, of course, that the Sinn Féin leadership would play a central role in the new political and social order.

There are other parts of the IRA/SF version of history which need to be challenged too, but which got hardly a mention in McGuinness – a documentary which gives far too much credit to Adams and McGuinness as if they had been negotiating in the late 90s from a position of strength.

In the early 1970s, the IRA’s campaign was an insurgency, and there was a real possibility that the British Government could be forced to withdraw from Ireland. Twenty years later, there was no such possibility, as the security forces had gained the upper hand. “No-go” areas were a distant memory and the IRA’s freedom of action in majority Catholic areas had been greatly curtailed, even in the previously-impregnable South Armagh.

The IRA of the 1990s was heavily infiltrated by the security forces, a point which Father Denis Faul used to hammer home when urging young Catholic boys in his County Tyrone school not to become foot-soldiers in their war.

“If you’re lucky, you’ll spend twenty years in jail. And if you’re not lucky, your mother will be handed a folded Tricolour at your graveside,” the priest who sat by the bedside of dying hunger strikers would tell them.

“And if you go to jail or die, it will sooner or later emerge that your commanding officer was a tout, and that his commanding officer was a tout too. And whilst you’re rotting away, they will be getting off scot-free.”

Unsurprisingly, the IRA came to hate Father Faul for speaking such truths, and this widespread infiltration prevented the IRA from causing anywhere near as much damage as they had previously, as an examination of the casualties suffered by the British Army shows. Over 100 British soldiers were killed by the IRA in 1972, for example. But in the final eighteen months of the “war,” after the IRA broke their ceasefire by bombing Canary Wharf in London, the same “army” could only inflict a handful of fatalities on the British army.

Faced with continuing a low-intensity and completely futile armed campaign, the IRA’s leadership chose peace and their organisation was gradually wound down in a manner which ensured that dissident splinter groups were never more than a minor threat. For accomplishing this much, Martin McGuinness deserves a good deal of acknowledgement, but not much gratitude.

The greatest shortcoming of McGuinness can be summed up in one word: Hume.

The references to the real leader of Northern nationalists over several decades in this documentary were far too limited. We are told in McGuinness that John Hume finished well ahead of McGuinness in elections in Derry in 1982 and 1983 – results which were repeated again and again, results which give the lie to the notion that the IRA’s campaign had majority support among Northern Catholics.

We are shown a video of McGuinness in the 80s, lamenting the fact that violence was necessary to bring about change. “I wish it could be done in another way. If someone could tell me a peaceful way to do it, then I would gladly support that. But no one has yet done that,” he says.

Of course, there was a peaceful way.

John Hume showed this by example every day from when the civil rights struggle began, and every day Martin McGuinness ignored this. There is even some evidence that the IRA considered murdering Hume because of his non-violence.

There is another aspect to the life of both men which the documentary makers hinted at without examining in detail, and that is the question of religious faith. Modern Ireland is sometimes too firmly attached to its secularism to delve into such matters, but the Derry which McGuinness and Hume were born into was a very different place indeed.

Hume left his native city to enter the seminary in Maynooth, before returning home to get married and be a teacher. McGuinness had no priestly ambitions, but his family’s religious instincts were obvious: his middle-name was Pacelli, in honour of Pope Pius XII.

At an early stage in the documentary, one of the interviewees discusses the young McGuinness’s reputation as a man of strong morals while the viewer is shown a faceless young man at prayer. Much later on, we are shown a video of McGuinness as he blesses himself at a funeral, perhaps that of a Republican comrade. We then hear words he spoke in the latter stage of his illness, as the camera slowly zooms out from the Derry graveyard where he is now interred.

Any historical documentary about a deceased political figure could conclude with an image of a graveyard.

A documentary titled Hume could end with the same image of the same graveyard, but this would not have the same meaning for a man who never caused another human being to die a premature death, and who never encouraged others to pursue a violent path when a peaceful one was available.

Sinn Féin’s false narrative is undercut by the existence of John Hume. For decades they wanted to be rid of him, and in their version of history, Hume is barely present at all, just as he is absent throughout most of the McGuinness documentary.

There is a reason for this and it must be challenged.

Ireland is at peace now. But it might not always be, particularly given that the Northern Irish state is so structurally unsound and prone to division. Wherever the temptation towards the use of violence exists, the need to exercise moral responsibility in politics is all the greater. When assessing the past, the achievements of Martin McGuinness in the latter period of his life should be acknowledged, but they should always be juxtaposed against the consistently peaceful example of John Hume.

When Derry’s two most famous sons are compared against one another, McGuinness falls very short indeed.

About the Author: James Bradshaw

James Bradshaw works for an international consulting firm based in Dublin, and has a background in journalism and public policy. Outside of work, he writes for a number of publications, on topics including politics, history, culture, film and literature.