“We pray continually that our God will make you worthy of his call.”

I.

How appropriate are these words of St. Paul at the beginning of this academic year! Indeed, how appropriate they are for a group of people who have devoted their lives or are preparing to devote their lives to a vocation in architecture. How appropriate are these words for people who have a desire to further the cause of goodness in the world in the form of beautiful buildings.

St. Thomas Aquinas in one of his comments concerning beauty quotes Dionysius the Areopagite, a famous and crucially important thinker both in Western and in Eastern Christianity, to the effect that “Goodness is praised as beauty.” Thomas agrees, all the while making an important distinction and making an important contribution to our understanding of our experience of beauty.

In the first instance he writes: “Beauty and goodness in a thing are identical fundamentally; for they are based upon the same thing, namely, the form; and consequently goodness is praised as beauty” (STh I, q. 5, a. 4, ad 1). Then, however, he adds that “they differ logically, for goodness properly relates to the appetite” while “beauty relates to the cognitive faculty; for beautiful things are those which please when seen” (ibid.).

II.

The experience of beauty arises when we delight in what we perceive with our intellects. As in the case of goodness, however, our sense of what is truly beautiful can become distorted. As a result we can delight in things that objectively lack beauty: they are either ugly or, even worse, simply banal. Banality is perhaps the aesthetic equivalent of the Nietzschean “beyond good and evil”.

To reiterate: our experience of beauty or the lack thereof relates to the intellect in the first instance. Art and architecture thus play a powerful role in shaping the way we think and behave. Indeed, art and architecture are all the more powerful when, as is unfortunately the case, most of us remain oblivious to the ways in which they shape our thinking and, ultimately, our behavior.

III.

If my memory serves me correctly, Martin Mosebach writes that in bygone times secular architecture took its cue from sacred buildings, which in turn were shaped by the celebration of the Eucharist. Human reason, shaped by faith in Christ really and truly present in the Eucharist, designed and crafted fitting abodes for the Eucharistic Lord. This faith-filled reason spread its influence beyond the confines of church buildings and, in that way, helped to shaped a general consciousness in society.

I do not wish to argue that beautiful churches designed and constructed within the flow of Tradition – for as the Dominican theologian, Marie-Dominique Chenu, points out, art and architecture are monuments of Tradition – are sufficient to bring people to a strong, orthodox Catholic faith. I would argue, however, that the rupture with Catholic traditions in music, painting, sculpture, and architecture over many decades has probably helped to undermine people’s faith. Put simply, such work embodies and communicates a philosophy that is not compatible with the faith.

IV.

Jesus said: Alas for you, scribes and Pharisees, you hypocrites! You who shut up the kingdom of heaven in men’s faces, neither going in yourselves nor allowing others to go in who want to.

Thus begins today’s Gospel passage. As people who have a special vocation to participate in God’s creative power by bringing beauty – and therefore goodness – into being, it’s necessary always to be conscious of the duty that attends such a privileged call, a call that extends to all of one’s work and not simply to sacred buildings.

Artists, sculptors, musicians, architects, and so on possess a certain power. Whether they are conscious of the fact or not, they mold the vision and values of the societies in which they live. Much contemporary art, music, sculpture, and architecture in Western society acts as a dispositive cause in obscuring a sense of the transcendent in general and of extinguishing the light of faith in particular. It shuts up the kingdom of heaven.

Christian artists, musicians and architects are called to be courageous and prophetic in their work as they act as a leaven in society. Persecution and trouble may well be their lot as a result. As Christians who espouse the one, true, holy, Catholic, and apostolic faith, however, none of us is exempt from Christ’s call to us to take up our crosses on a daily basis and to follow Him.

V.

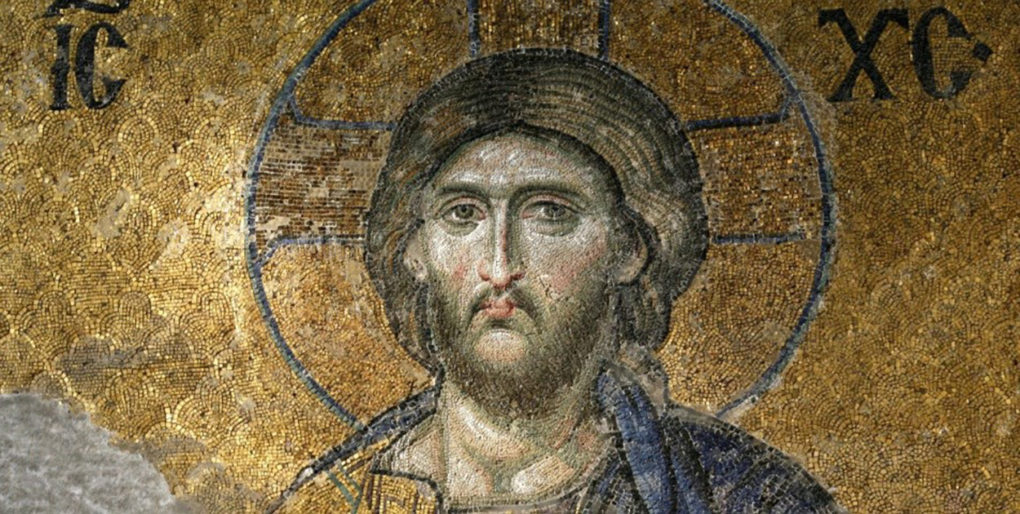

A vocation to beauty may well bring suffering in its wake but suffering will never have the final word. The crucified Lord has risen from the dead and thrown open the gates of heaven for us. In this life a vocation to beauty will bring many glimpses of the glory of the world to come. The artistic beauty inspired by the incarnation of the second Person of the Holy Trinity offers an index of the transformation that the grace of the Gospel has wrought in Western civilization over two millenia.My plea to you is to immerse yourselves in that grace in the sacramental life of the Church, particularly in the Eucharist. With St. Paul in today’s reading to the Thessalonians

We pray continually that our God will make you worthy of his call, and by his power fulfil all your desires for goodness and complete all that you have been doing through faith; because in this way the name of our Lord Jesus Christ will be glorified in you and you in him, by the grace of our God and the Lord Jesus Christ.

About the Author: Fr Kevin O’Reilly

Fr. Kevin E. O’Reilly, is a member of the Irish Province of the Order of Preachers. He is the author of Aesthetic Perception: A Thomistic Perspective and The Hermeneutics of Knowing and Willing in the Thought of St. Thomas Aquinas. He currently teaches moral theology at the Pontifical University of St. Thomas Aquinas (Angelicum) in Rome.This homily was given during Mass at San Clemente, Rome to the professors and students of Notre Dame’s Architectural School’s one-year programme in Rome.