The Swinging Sixties were characterized by a sexual liberation the likes of which history had never experienced before – thanks to the combination of philosophy and technology, namely existentialism and the pill. These resulted in unfettered freedom (licence) and the primacy of the pleasure principle. The philosophy was articulated by Sartre and de Beauvoir but it fed into an underlying utilitarianism, one of the undercurrents of Western culture since the Enlightenment. Since, for Sartre, there is no creator God, then there is no nature. And if there is no such thing as a common human nature, then there is no such thing as a perennial, universal moral order arising out of our very humanity. In a word, there is no such thing as objective morality. The founder of modern Feminism, de Beauvoir, saw the significance of freely available contraception and abortion on demand, as liberating woman from the slavery imposed on her by a woman’s own biological make-up and so enabling woman to be as self-transcendent and creative as man.

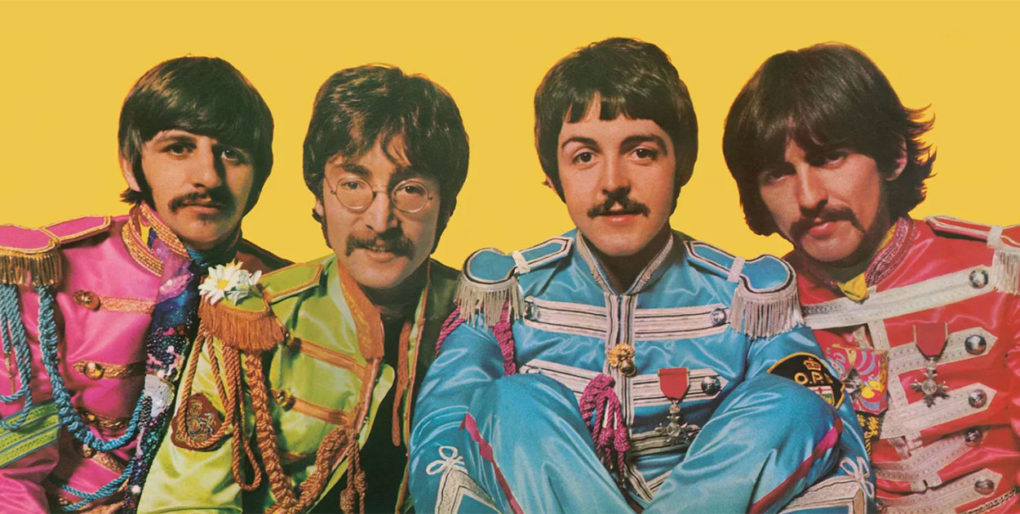

The basic thrust of existentialism was largely disseminated by pop-music. What started out at the beginning of the 1960s as relatively harmless (Elvis Presley) was radically transformed by the Beatles’ chart-topping album: Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. According to the Wikipedia article, “the album was lauded … for providing a musical representation of its generation and the contemporary counterculture.” More radical were pop-stars like Mick Jagger of the Rolling Stones (Sympathy for the Devil), who song, Street Fighting Man, summoned youngsters to the barricades in 1968. Jagger’s songs extolled “the transvaluation of all values and the confusion between appearance and being” (Phillipe Margotin and Jean Michelle Guesdon ).

The effect of such a radical change in moral sensitivity would soon find legal expression. The legal dam break came with the US Supreme Court decision in Griswold v. Connecticut (1965) which ruled that the Comstock Law forbidding contraception was unconstitutional. And two years later, in 1967, Westminster, the Mother of all Parliaments, legalized abortion; the rest of the world would soon follow suit.

The proclamation of Humanae Vitae on the 29th July 1968 amounted to little less than a rejection of the very basis of the 1960s’ sexual liberation. But, indeed, its significance touched on more than sexuality. Apart from rejecting the essentially technological solution to birth control (artificial contraception, especially the pill), the encyclical also rejected the fundamental [im]moral principle that the end justifies the means (or to do evil that good may come of it: see HV 14, with ref. to Rom 3:8). That was the same principle which at the macro-level in Marxism justified sacrificing hundreds of thousands of innocent human beings with the objective of achieving utopia. The same principle had been used by the USA to justify dropping the atom-bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki to end the war.

Humanae Vitae shocked that brave new world to its core. The Western media was in uproar. Almost immediately, theologians expressed their public dissent by the essentially political act of publishing manifestos in the media and gathering hundreds of signatures. (This, too, a historical first!) Some Episcopal Conferences, under the influence (or the pressure?) of the same theologians, issued ambiguous statements – ostensibly welcoming the teaching in general but indicating clearly that couples who might not agree should follow their conscience (understood as private judgement) – in other words ignore the Papal Teaching. How did this happen?

The general euphoria after the Council included a growing feeling that even traditional Church teaching on morality could change. Vatican II had mandated theologians to find a new approach to moral theology. The Majority Report of the Birth Control Commission advising Pope Paul VI voted for change in the traditional teaching. In hindsight, it could be said that the renewal of moral theology demanded by Vatican II was not sufficiently developed at the time for dissenting theologians to be able to accept Humanae Vitae. Most moral theologians, such as Charles Curran and Bernard Häring, were still working within the fundamentally legalistic, indeed casuistic mental framework of the pre-Conciliar manualist tradition, while, at the same time, vociferously rejecting the same tradition!

The required renewal of moral theology only became possible with the recovery of virtue (as articulated by Aristotle and Aquinas) as the theoretical framework for moral reflection, a recovery which only began to mature in the 1980s and found its first expression in the fundamental moral section of the Catechism of the Catholic Church (1992).

The teaching of Humanae Vitae can only be understood in terms of virtue, more precisely the virtue of chastity within marriage. This in turn is predicated on the existence of an objective moral order arising from our common humanity created by God (cf. Rom 1:18 – 2:12, espec. 2:14-16). Existentialism – the underlying philosophy of the 1960s – denied, as mentioned above, that there was any such thing as objective morality, since, they claimed, there is no creator God; man is absolutely free to choose and so create himself as a future project.

Rejecting this, Humanae Vitae teaches that there are certain actions (few in number) that are wrong in themselves since they contradict the moral order arising from our human nature and so can never be justified even for the most noble or desirable of ends. Such actions do not make us virtuous or draw us closer to God. An approach to moral theology based on a calculus of foreseen consequences (proportionalism, a version of utilitarianism) denies that any such actions are intrinsically wrong. It leads to a morality that is literally unprincipled: and so the end justifies the means. By way of contrast, morality understood in terms of virtue is concerned with character, integrity, principle – and with growth in grace, union with God. Further, it assumes a common human nature created by God and defined by its own moral order arising from our bodily/spiritual composition (cf. Rom 2:14-16), what is traditionally understood as natural law (or primordial conscience), difficult though it is to articulate.

Pope Paul VI’s prediction (HV 17) of the negative social effects of widespread contraception was prophetic: increased marital breakdown, abuse of women, State-imposed birth control, etc. The separation of the unitive and generative significances of conjugal intercourse led not only to the trivialization of sex (now seen as a mere “leisure activity”) and the dramatic increase in sexually transmitted diseases but also to the making of babies in the laboratory (IVF) and, more recently, to so-called gender theory. The demographic consequences of the rejection of Humanae Vitae are becoming more and more acute with most European nations facing a demographic winter – making Europe dependent on mass migration, which in turn is producing a populist backlash arising from fears of a radical change of European culture and identity.

But the most significant effect of the rejection of the teaching of Humanae Vitae might well be the way that rejection – by embracing the principle that the end justifies the means – undermines the primacy of personal integrity (virtue) and so fosters corruption in society, the main source of injustice. The macro-level of society and the micro-level of the human person are, after all, intrinsically related to each other. And both are related to God. The divine cannot be excluded either from society or from the most intimate realms of our human lives without catastrophic effects in the long term.

About the Author: Fr D. Vincent Twomey

Fr D. Vincent Twomey is a member of the Divine Word Missionaries and professor emeritus of moral theology, Pontifical University, Maynooth. Among his published works are: The End of Irish Catholicism? (Dublin, 2003), and Benedict XVI. The Conscience of Our Age: A theological Portrait (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2007). This article is adapted by the author from a longer version which appears in the missiological quarterly