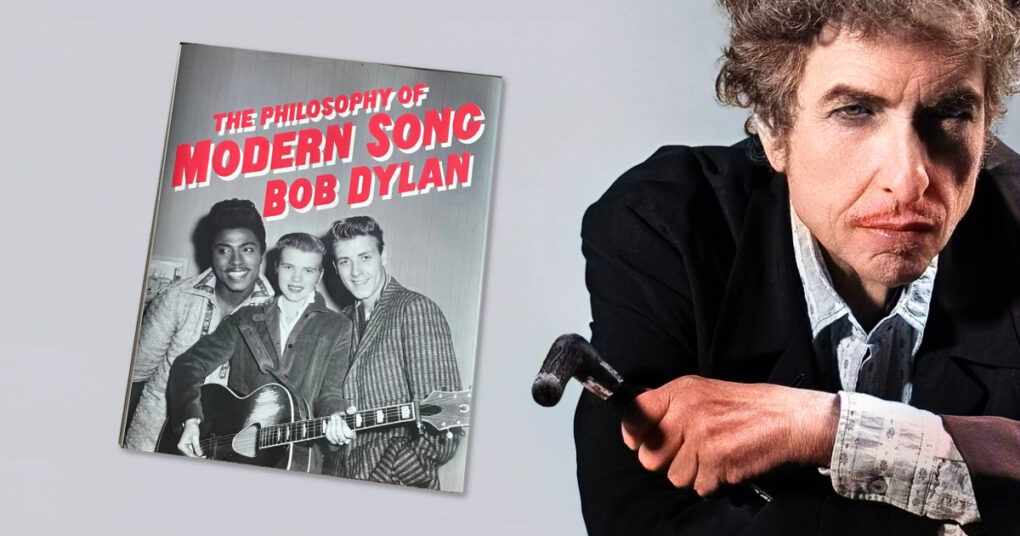

Bob Dylan has been writing songs all his life. But he has also been thinking about songs, others’ songs, all his life. In 2022 his reflections on the songs which have dominated or influenced popular culture in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries were made public in a remarkable volume published by Simon and Schuster. Entitled The Philosophy of Modern Song, the book is almost a hybrid of a True Detective volume and a work of existential philosophy. A friend of mine, after looking at the visual appearance said he thought it wasn’t worth a second look. But when I quoted a few passages from it he changed his mind.

Dylan seldom, if ever, talks about his own songs. What he has written he has written. They speak for themselves, like all great art. On interpretations of his work – of which there are multitudes – he remains silent, with the exception implied in his famous self-description as “a song and dance man”.

But this silence does not apply to what he has been listening to in the broad popular musical culture of the past century – and even beyond. In The Philosophy of Modern Song we have an extraordinary collection of reflections on songs from what is often called The Great American Songbook – with a handful of British for good measure, – ranging from a haunting song by Stephen Foster from the nineteenth century down to the last years of the twentieth. From each song, some of them apparently banal, sometimes briefly, sometimes at more length, he draws out existential interpretations of our times and the world in which we live.

Bob Dylan’s Philosophy of Modern Song is mainly a celebration of a culture – or a segment of our culture. It revisits sixty-six popular songs which in different ways reflect the simple joys and sorrows, the worries and anguish of a people – mainly North American – in the twentieth century. Dylan does not evaluate them on any commercial basis and the songs which were never part of that exploitation, those heard by downtrodden people in impoverished communities, were of equal interest to him in articulating what he saw as this philosophy of our time.

For example, in a rather harrowing reading of a rather dark song called Take Me From The Garden of Evil, he begins calmly enough but then rises to a Jeremiad of existential anguish with echos of Psalm 37 and reminiscent of anything in Albert Camus’ bleaker novels. Take your pick. Inevitably all this is written in Dylan’s own inimitable style.

He begins, where the song does, telling us about the world we would like to live in and in which many people do:

“What you’d like to see is a neighbourly face, a lovely charming face. Someone on the up and up, a straight shooter ethical and fit. Someone in an attractive place, hospitable, a hole in the wall, a honky-tonk with home cooking. Nobody needs to be in a quick rush, no emphasis on speediness, everybody’s going to measure their steps. Your little girl will support you; she waits on you hand and foot, and she sides with you at all times.”

Then he looks at another world, negative and all too familiar, from which the songwriter is praying to escape – and in the end appears to have the determination to do so.

“But you’re in limbo, and you’re shouting at anyone who’ll listen, to take you out of this garden of evil. Get you away from the gangsters and psychopaths, this menagerie of wimps and yellow-bellies. You want to be emancipated from all the hokum. You don’t want to daydream your life away, you want to get beyond the borderlands and you’ve been ruminating too long.

You’ve been suspended in mid-air, but now the stage is set, and you’re going to go in any direction available, and get away from this hot house that has gone to the dogs. The one that represses you, you want to get away from this corrupt neck of the woods, as far away as possible from this debauchery. You want to ride on a chariot through the pillars of light … put money on it. You overpower your fears and wipe them out, anything to get out of this garden of evil. This landscape of hatred and horror, this murky haze that fills you with disgust.

You want to be piggy backed into another dimension where your body and mind can be restored. If you stay here your dignity is at risk, you’re one step away from becoming a spiritual monster, and that’s a no-no.

You’re appealing to someone, imploring someone to get you out of here. You’re talking to yourself, hoping you don’t go mad.

You’ve got to move across the threshold but be careful. You might have to put up a fight, and you don’t want to get into it already defeated.”

That’s at the dark end of his reflections but who can say that it does not resonate with our experience of dimensions of the world we see around us?

On a more sublime and sad level we have this enigmatic reflection on the reality of a society which has side-lined God in its reading of the human condition. In his reading of a poignant little love song from 1972, If You Don’t Know By Now, he writes:

“One of the reasons people turn away from God is because religion is no longer in the fabric of their lives. It is presented as a thing that must be journeyed to as a chore – it’s Sunday, we have to go to church. Or, it is used as a weapon of threat by political nut-jobs on either side of every argument. But religion used to be in the water we drank, the air we breathed. Songs of praise were as spine-tingling as, and in truth the basis of, songs of carnality. Miracles illuminated behavior and weren’t just spectacle.

It wasn’t always a seamless interaction. Supposedly, early readers of the Bible were disturbed by the harshness of God’s behavior against Job, but the prologue with God’s wager with Satan about Job’s piety in the face of continued testing, added later, makes it one of the most exciting and inspirational books of the Old or New Testament.

Context is everything. Helping people fit things into their lives is so much more effective than slamming them down their throats. Here’s another way to look at a love song.”

He could be searing in his reading of our time as well as benign and optimistic. God is present in Dylan’s vision of the world and the things that offend God are real to him.

On the subject of what America has done to the institutions of marriage and the family he offers us what is perhaps his most bitter and telling reflection. He jumps off on this one from a platform offered by a mock cynical Johnny Taylor song called It’s Cheaper to Keep Her.

He writes that soul records, like Hillbilly, Blues, Calypso, Cajun, Polka, Salsa, and other indigenous forms of music, contain wisdom that the upper crust often gets in academia. The so-called school of the streets is a real thing. “While Ivy League graduates talk about love in a rush of quatrains detailing abstract qualities and gossamer attributes, folks from Trinidad to Atlanta, Georgia, sing of the cold hard facts of life.” The divorce now becomes his target.

“Divorce is a ten-billion-dollar-a-year industry. And that’s without renting a hall, hiring a band or throwing bouquets. Even without the cake, that’s a lot of dough.

If you’re lucky enough to get into this racket, you can make a fortune manipulating the laws and helping destroy relationships between people who at one point or another swore undying love to one another. Nobody knows how to pull the plug on this golden goose, nor do they really want to. Most especially not those who risk nothing but who keep raking it in.

Marriage and divorce are currently played out in the courtrooms and on the tongues of gossips; the very nature of the institution has become warped and distorted, a gotcha game of vitriol and betrayal. How many divorce lawyers are parties to this betrayal between two supposedly civilized people? The honest answer is all of them. This would be an unimportant economic slugfest if it was just between the estranged parties.

After all, marriage is a pretty simple contract – till death do you part. Right there is the reason that God-fearing members of the community regularly gave divorced folks the skunk-eye. If they were willing to disavow that basic contract, what makes you think they won’t disavow anything and everything?

That’s why historically, if you were a divorced person nobody trusted you.

Marriage is the only contract that can be dissolved because interest fades or because someone purposefully behaves badly. If you’re an engineer for Google, for example, you can’t just wander over to another company and start working there because it’s suddenly more attractive. There’s promises and responsibilities and the new company would have to buy out your contract. But people seldom think logically when breaking up a home.

Married or not, however, a parent has a duty to support a child. And this matters a whole lot more than divvying up summer homes. Ultimately, marriage is for the sake of those children.

But divorce lawyers don’t care about familial bonds; they are, by definition, in the destruction business. They destroy families. How many of them are at least tangentially responsible for teen suicides and serial killers? Like generals who don’t have to see the boys they send to war, they feign innocence with blood on their hands.

They say married by the Bible, divorced by the law – but will your lawyer talk to God for you? The laws of God override the laws of man every time but clearing the moneylenders from the temple is one thing – getting them out of your life is another. If people could get away from the legal costs, they might have a better chance to keep their heads above water.

And then there are prenuptial agreements. You might as well play blackjack against a crooked casino. Two people at the height of their ardor lay a bet that those feelings won’t last. They pay lawyers to make sure that whoever has the most assets has that money protected when they start getting mad at each other. Now, those same lawyers will tell you that it’s just a precaution and in many cases these agreements never have to get implemented. But look a little closer and what you realize is these lawyers have even figured out how to get paid way in advance, and indeed, in lieu of a divorce.”

The LA Times and other bastions of liberal progressives did not like all that of course. For them it was misogynistic and backward looking. Dylan, as always, is fearless. While on many occasions he defended those treated unjustly – like the unjustly convicted “Hurricane” Carter in Hurricane – he never did subscribe to any ideology. It was said recently in a Free Press column by Michael Moynihan that the break between him, Pete Seeger, and the folk movement at the Newport Festival had more to do with his failure to subscribe to their socialism than with electricity.