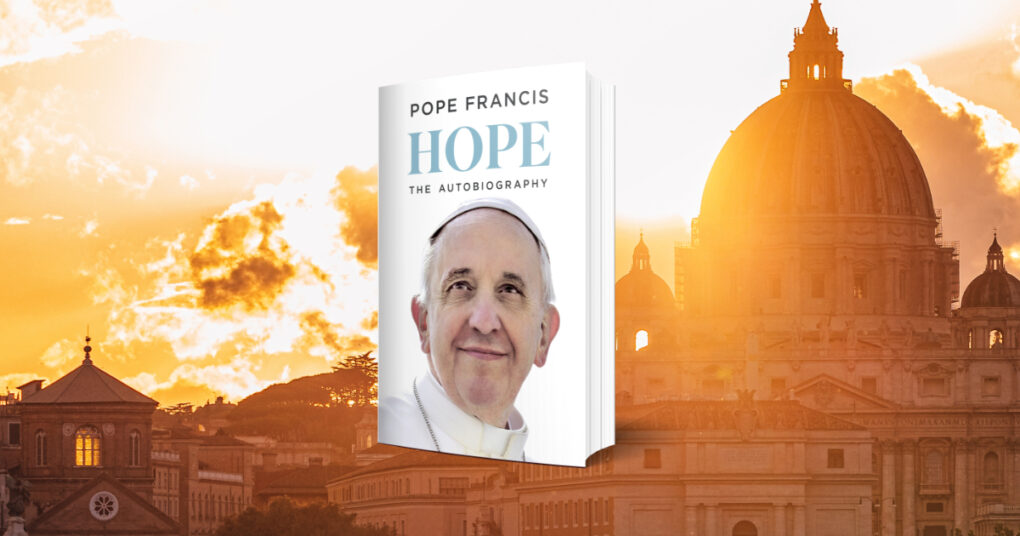

HOPE: The Autobiography

Pope Francis

Viking

January 2025

320 pages

ISBN: 978-0241764107

Introduction

Pope Francis is the first non-European to hold the office of the papacy. That in itself was enough to ensure that his would be a very different kind of papacy from that of his predecessors. But, as emerges during the course of this autobiography, he is also somewhat unique in his focus on a single concern, namely the plight of those on the peripheries of society, in particular the poor, victims of war and emigrants. As he himself says in the book: “When someone says that I’m a papa víllero (a Pope of the shanty-towns), I pray only that I might always be worthy of it.”

This book tells the story of what made an Argentinian born of Italian stock to become a papa víllero. It becomes increasingly clear that the Pope is a man for whom the plight of the down-trodden is paramount, and for whom other issues are secondary. For instance the problem of secularism, which so deeply concerned Pope Benedict XVI, is considered by Pope Francis to be a bit of a non-problem: “But there is no more secularization in the Church now than in former times…. the worldly spirit has always been there.” Liturgical and ethical matters similarly and are to be judged overwhelmingly in terms of pastoral, not aesthetic nor doctrinal, demands.

Revealing the man

From the outset of the autobiography We see a picture of an intensely sociable person, a person who in his own words, needs “to live my life alongside others”. The young Jorge Borgolio spent the first twenty-one years of his life in the same house in the middle class Flores neighbourhood of central Buenos Aires, a “barrio” which he describes as “a complex, multiethnic, and multicultural microcosm”. He writes with great fondness of the myriad characters of the barrio, the local football team San Lorenzo, as well as the víllas míserías – shanty-towns – around Buenos Aires with which he became deeply acquainted as a priest and later bishop. Pope Francis has clearly been deeply marked by his early exposure to the wide range of humanity in the barrio and the víllas míserías. He speaks quite frankly of the local women who ended up in prostitution, and of one particularly heroic prostitute who spent her declining years caring for women who had been forced into the same profession.

The one person who dominates the early life of the young Bergoglio is his paternal grandmother, Rosa Vassallo, who joined the mass migration of Italians to Argentina at the start of the twentieth century, with her husband and only son, the Pope’s father. It was from this strong-willed and devout woman that he imbibed more than from any other, his own Catholic piety. She had been very involved in the Catholic Action movement in Turin as a young woman before emigrating to Argentina, and experienced at first hand the harsh opposition of Mussolini’s Blackshirts. Later she regarded their “authoritarianism, the brutal methods of the fascist squads, totalitarianism, the cult of violence and war, and then the persecutions and deportations as rejections of the Gospel spirit and of fraternity.” His grandfather’s experiences in the First World War left him with a strong aversion to monarchy. It would seem that the hard experiences of these immigrant grandparents, (on both sides, as his maternal grandparents also emigrated from Italy) left him with a marked sense of the need for social justice and a strong aversion to anything which gives off a whiff of fascism; later he speaks of contemporary intolerance and xenophobia and asks pointedly: “Doesn’t all of this remind you of something?”

Three big themes

In fact the three dominant concerns of the Pope (at least as revealed in this work) – emigration, war and the need for social justice – all appear rooted in the experiences of his youth. The theme of the plight of emigrants features from the very first page of the book, with his grandparents’ close brush with disaster. The hard experiences of his Piedmontese grandparents as they fled the poverty of post-war Italy dominate the first chapters of the book. The theme later reappears when the Pope’s concern for the plight of suffering migrants is recounted, for instance in his visits to war-torn Mosul in Iraq, and especially to the migrants stranded in camps on the Greek island of Lesbos – something which clearly affected the Pope very deeply: “The camp looked immediately like one of the circles of Dante’s hell: human suffering, rags, mud, corrugated iron, misery” he writes.

The second dominant theme is that of the folly of war, and this appears to be rooted in the harrowing experience of his own paternal grandfather Giovanni Angelo Bergoglio who spent many months in the trenches on the border between Italy and Slovenia: “Nono described the horror, the pain, the fear, the absurd alienating pointlessness of the war.” And this is a theme that the Pope returns to many times during the course of the book, referring to the dozens of wars which currently rage around the world, and in particular of course to the wars in Ukraine and in Gaza. The Pope is particularly passionate on the theme of war, and is clearly disturbed in particular by the sufferings inflicted on innocent children in these wars: “War, every war, is sacrilege because peace is a gift of God…”. “War is a lie in itself.” In the light of the personal experience of the Superior General of the Jesuits, Father Pedro Arrupe, who was rector of the Jesuit noviciate at Hiroshima when the atomic bomb was dropped on August 6, 1945, the Pope warns of the spectre of nuclear war hanging over the world, and speaks of the immorality of nuclear weapons.

The third dominant theme is that of social justice. Already the young Bergoglio had imbibed a certain political radicalism from his grandparents, and a strong sense of injustices suffered by opponents of fascism back home in Italy. This concern for social justice was heightened during the decades of political turmoil in Argentina from the 1940s to the 1980s, in particular the Guerra sucia or Dirty War marking the period of state sponsored terrorism from 1974 to 1983. From 1973 to 1979 he was provincial superior of the Society of Jesus in Argentina and so was particularly caught up in the turmoil of the time. Pope Francis speaks of several of the victims who disappeared at the hands of of state terrorism – the desaparecídos – and in particular of Esther Ballestino de Careaga who was teacher at his technical school and who, in 1977, was seized by the political police on account of her communist leanings never to be seen again. Pope Francis comments on his sympathy with some of her views, but reflects ruefully that “communists stole the flag from us because the flag of the poor is Christian…”.

Pope Francis was deeply affected by the experiences of this time (and points out that he was helped by a psychiatrist for a year to cope with what he had gone through), and clearly takes to heart the struggle against injustice, something which he always found in the doctrine of the Church “that urges us to fight against every form of injustice, without allowing us to be swept away either by ideological colonisation or by the culture of indifference.” Allied to this is a certain visceral dislike for anything that smacks of the bourgeois in the Church: “I prefer a Church that is broken, wounded, and dirty for having gone out on the streets, rather than a Church that is feeble and sick for having closed itself up and clung on comfortably to its safety.”

Stridency

In his broadly positive review of the book Nicole Winfield of the Associated Press observes however that the Pope “is strident in defending his sometimes controversial decisions”, a criticism which appears to me valid. This stridency appears when Pope Francis addresses topics about which he is clearly passionate: war, immigration and the death penalty being examples. He claims that “the possession of atomic weapons is immoral”, the death penalty “is unjustifiable”, and appears to denounce any restrictions on the movements of migrants. He does not appear to allow for the complex nature of these matters, nor for the legitimacy of the contrary opinion. Perhaps part of the problem is that Pope Francis is such a pastoral pope, not a theologian, or philosopher like his two predecessors. He speaks grosso modo, almost for effect and his words should be taken bearing this in mind.

There is one theme however where Pope Francis’ tone goes beyond the simply strident and that is in the matter of traditionalism in liturgy: the preference for the use of Latin and for ornate vestments: “It is curious to see this fascination for what is not understood, for what appears somewhat hidden, and seems also at times to interest the younger generations. This rigidity is often accompanied by elegant and costly tailoring, lace, fancy trimmings, rochets. Not a taste for tradition but clerical ostentation….” He even claims such tastes might be linked to mental instability. Clearly in this Pope Francis parts company with many of the Church’s saints; we only have to think of St John Vianney’s desire that the vestments for his little church would be “the best that could be got”.

Conclusion

Although this work has been billed as “the first autobiography in history ever to be published by a Pope”, that claim is a slight exaggeration given that there have been long quasi-autobiographical interviews with previous Popes, and even an autobiographical memoir published by Pope Pius II in the fifteenth century. Furthermore, it is clear that the co-author/ghost-writer Carlo Musso has used, as he says himself, “numerous meetings, conversations, and the study of public and private texts and documents” to construct much of the book, inevitably producing a bit of a patch-work quilt of a book. Another effect is to produce a slightly “and the moral of the story is” feel to the book, since events related to the life of the Pope are often followed with moral reflections taken from the preaching of the Pope. The long and dramatic account of the sinking of the “Italian Titanic” – the SS Principessa Mafalda – in October 1927 with which the book begins is a case in point. At the end of the account we learn that Pope Francis’ grandparents had bought their tickets for that sailing but in the end didn’t take the ship. The event appears to be included as a device to draw comparisons with the tragic plight of contemporary migrants losing their lives in the Mediterranean Sea.

The book would benefit from more contextualisation, at least for non-Argentinian readers. There is a certain presumption that the reader has some prior knowledge of Argentinian politics of the period from the 1940s and 1980s, in particular of Peronism, and of the Dirty War in the 1970s and 1980s.

And finally given the seemingly large role played by Carlo Musso in the work, one wonders if the term “autobiography” can correctly be applied to it. Inevitably the work of selection of incidents in the life of the pope, and the use of existing texts and omission of others, is already a work of subjective interpretation rather than objective presentation. Nevertheless its primary interest is in revealing the formative experiences which shaped this Pope of the shanty-towns.

About the Author: Rev. Gavan Jennings

Rev. Gavan Jennings is a priest of the Opus Dei Prelature. He studied philosophy at University College Dublin, Ireland and the Pontifical University of the Holy Cross, Rome and is currently the editor of Position Papers.