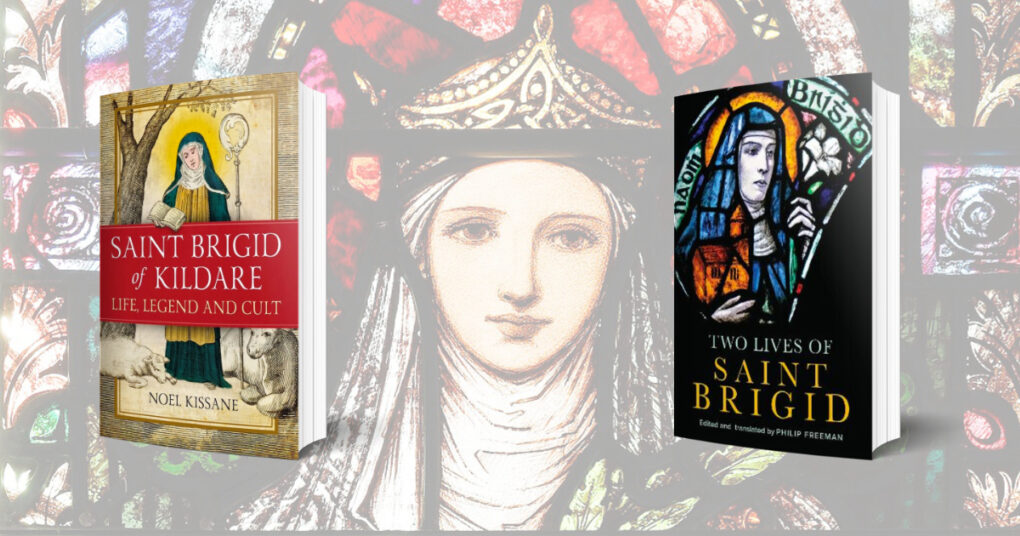

Saint Brigid of Kildare: Life, Legend and Cult

Noel Kissane

Four Courts Press

2017

352 pages

ISBN: 978-1846826320

Two Lives of Saint Brigid

Philip Freeman

Four Courts Press

Feb. 2024

192 pages

ISBN: 978-1801511162

St Brigid’s Day is not like it used to be. Time was when the saint’s feast day marked not only the beginning of spring but a moment of fervent prayer for protection over one’s family, crops, livestock and home. Yet popular devotion to St Brigid has been on the wane for over a century. When testimonies of traditional prayers and devotions invoking St Brigid were gathered by the Irish Folklore Commission in the 1940s, most of the witnesses were recalling practices that had been popular in their childhood, some fifty or sixty years earlier.

Nevertheless, her legacy is significant. “St Brigid is one of the most remarkable women in Irish history”, writes Noel Kissane in his book, St Brigid of Kildare: Life, Legend and Cult. It’s a bold statement, given that he admits that:

“Little is known of the saint other than that she probably lived in the general period c.450-550 and that she was involved in the establishment of the great double convent and monastery at Kildare (the first such institution in Ireland) and that most likely she was its first abbess.”

Joining St Patrick and St Colmcille as national patrons, she is the foremost female saint of Ireland. Place names (such as Kilbride) immortalise her, running St Patrick into second place. They are found in all four provinces, especially Leinster. There are numerous holy wells and church dedications. Indeed, through Irish missionaries, her cult spread overseas to Britain and the European mainland.

Kissane’s lengthy book – running to over 350 pages – comprises a review of the history of St Brigid’s cult from her lifetime down to the present time, as evidenced in folklore, place-names, holy wells, church dedications, relics and the naming of girls after her. It is not an apology for the Catholic faith since sceptical views feature also. Yet it contains a wealth of interesting information.

In a chapter examining St Brigid’s Ireland, Kissane describes how her life must have been and how Christianity became so firmly rooted in her country. Following a survey of the pioneering missionary work of Palladius and Patrick and others, Kissane quotes Charles-Edwards’ assertion: “By the time of the first centenary of Palladius’s mission [531, around the time of St Brigid’s death] it was probably clear that Irish paganism was a lost cause.”

It is a measure of her importance that so many wish to appropriate the real St Brigid’s virtues to their own ideological cause. In Ireland a public holiday to mark “Imbolc/St Brigid’s Day” was established in 2023. Seven years earlier, a government statement said that it would be the first Irish public holiday named after a woman and that all four of the traditional Celtic seasonal festivals “will now be public holidays” (cf. Newstalk, Nov 2016).

To associate the Feast of St Brigid with the celebration of the contributions of Irish women makes sense to a degree. Her fame extends well beyond Ireland, thanks to her sanctity. St Brigid was a holy Irish woman who performed extraordinary works of charity and generosity, founded two ecclesiastical institutions and was reputed to have worked many miracles during her life. For example, when the mother of the mediaeval mystic St Bridget of Sweden was caught in a life-threatening sea storm during her pregnancy, she invoked St Brigid of Ireland who had a great reputation in Sweden, promising that she would name the child after her.

Miracles attributed to the Irish saint’s intercession include cures, restoration to their owners of stolen goods or lost property, bountiful provision of food for unexpected guests from meagre resources, and conversion of water into beer. One of a different kind that struck me upon reading it was a tale of marital strife as recounted in Two Lives of St Brigid:

“A husband came asking that holy Brigid bless water for him that he could sprinkle on his wife. For the wife hated her husband. Then Brigid blessed water and the home was sprinkled with water along with the food and the drink and the bed, all while the wife was away. And from that day the wife loved her husband with love beyond all measure as long as she lived.”

Implicit in this story is the sanctity of marriage between one man and one woman till death do them part. How could such a saint appeal to modern feminists? At first sight it’s hard to see what Englishwoman Maud Gonne (1866-1953) turned Irish cultural revivalist might have in common with St Bridget of Sweden (c.1303-1373). Nevertheless, both women had St Brigid of Ireland as their patron. Inghinidhe na hEireann (Daughters of Ireland) was established in Dublin in 1900 under St Brigid’s patronage by a group of women led by Maud Gonne. The organisation had diverse goals such as advocating Irish independence by force, promoting women’s suffrage and supporting reforms such as the provision of free school meals for poor children. The latter goal St Brigid would most certainly have agreed with.

Writing in this publication some years ago, Brenda McGann (Position Papers, March 2016) recalled how:

“On a visit to St Patrick’s Cathedral in New York some years ago I was very moved on reading that the people who gathered the money together to buy the site on Fifth Avenue where it now stands were the “Brigids” of New York as they were known by in those days – in other words the very many Irish women who emigrated and found work as nannies or domestic helpers in a city that was not particularly welcoming to Catholics.”

While more festivals (e.g. the “Brigit Festival” in Dublin) are being organised in her name, fewer girls are being named after St Brigid. This is a real pity, for St Brigid was a real person, a real saint and a truly remarkable woman. Her lifetime of about sixty years would have begun in the second half of the fifth century and ended in the first half of the sixth. Her mother was Broicsech, her father Dubhtach. Brigid became a Christian in her early teens. She looked after cattle and calves. Her charity was boundless. As a Christian she was determined to lead a celibate life dedicated to the service of God. This she did in an outstanding manner for several decades of her life. Her memory is honoured through the customs of making St Brigid’s crosses, through the traditional meal on St Brigid’s Day (a supper of potatoes and freshly churned butter, followed by barm brack, apple cakes and tea) through the many places and institutions named after her, and through the annual liturgical celebrations of her feast.

Every few years fresh publications and lives of St Brigid appear. But it’s best to return to the sources. In that respect, Philip Freeman’s Two Lives of St Brigid makes a welcome contribution. Freeman, based at Pepperdine University in California, offers: “for the first time translations of both Lives along with the Latin texts for interested readers, students and scholars, with the hope that it will provide a resource for further research and study.”

The excellent Preface to the book gives a very accessible summary of St Brigid’s life and the hagiographical lives written about her. Acknowledging that some aspects of the goddess Brigid are probably present in the stories of the saint, Freeman is quick to point out that:

“… efforts to present St Brigid as a thinly-veiled pagan figure from an earlier time – a kind of baptized goddess – are well-meaning but misguided. The Brigid we have from her earliest stories and later traditions is an orthodox Christian devoted to good works as a means to serve God and spread the Gospel.”

He contrasts the two earliest lives of Brigid, namely, the Life of St Brigid by Cogitosus and the anonymous Vita Prima. Cogitosus dates from the mid-seventh century about a hundred years after St Brigid. Freeman notes that: “His writing shows a strong bias towards the primacy of the church at Kildare as opposed to the rival ecclesiastical seat at Armagh.”

The anonymous Vita Prima, which was composed later, is more than twice the length of Cogitosus’ Life. But besides the length:

“…the primary difference between the two Lives is that in the Vita Prima Brigid frequently travels across all the provinces of Ireland, with Kildare mentioned only once, giving it a sense of a national rather than local narrative. Cogitosus, on the other hand, has Brigid leave the area of Kildare only once and then she does not travel far.”

Moreover in the Vita Prima Brigid “meets St Patrick a number of times and is clearly portrayed as subordinate to him”. This bears out the view that Vita Prima was written by an author “with a political agenda supporting Kildare’s rival church in Armagh”.

Nothing if not thorough, Freeman does not neglect to mention a third early life story of St Brigid, the Bethu Brigte, a copy of which he states “has been admirably edited and translated by Donncha O hAodha”.

As Spring and the lambing season begins again, let us not lose sight of the Real St Brigid who inspired so many devotions, hymns, writings and traditions. There are many good studies about this Irish woman worthy of attention. Readers are encouraged to study them rather than rely on mass-mediated and confused interpretations of this saint’s and our country’s history.

About the Author: Fr James Hurley

Fr James Hurley is a priest of the Opus Dei Prelature and is the parish priest of Merrion Road Parish in Dublin.