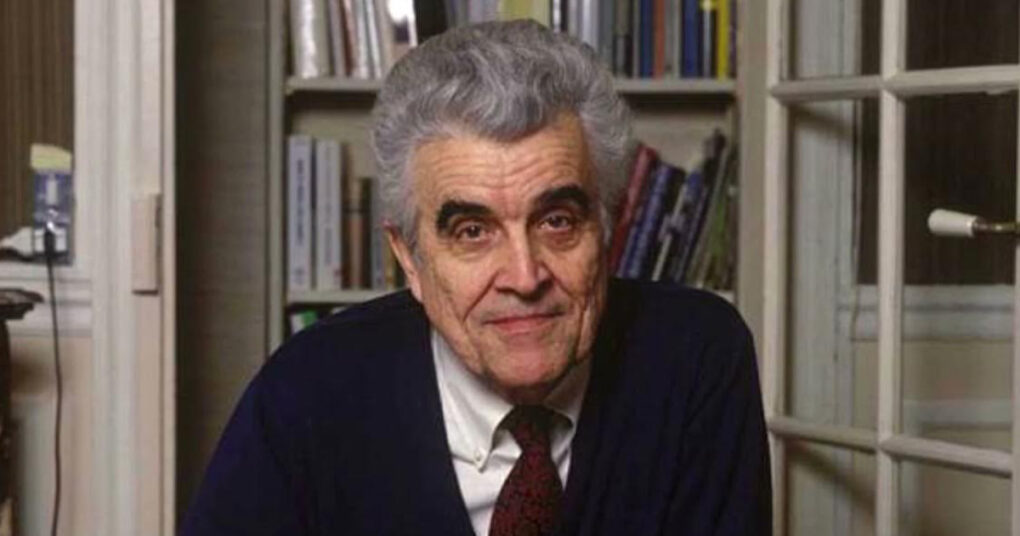

René Girad was born into a Catholic family in Avignon in France on 25 December 1923. His father, Joseph Girard, was a historian. René studied medieval history at the École des Chartes, Paris. In 1947, Girard went to Indiana University. He was to spend most of his career in the United States. Although his research was in history, he also taught French literature. A multi-disciplinary character was a marked feature of his academic interests. This facilitated his occupation of positions in a variety of prestigious institutions – at Duke University, Bryn Mawr College and Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, where he became a full professor in 1961.

In 1981, Girard was appointed Professor of French Language, Literature, and Civilization at Stanford University, where he remained until his retirement in 1995 and subsequently in an active emeritus role. On 17 March 2005, Girard was elected to the Académie Française.

Throughout these years he published just short of thirty books, covering all the interlocking disciplines which were the subjects of his thought and research,

Girard’s reading of Dostoevsky, in particular The Brothers Karamazov and The Possessed (Demons) – especially the deathbed conversion of Stepan Verkhovensky in that book – were influential in his conversion from agnostic to Christianity. But equally important was where his reading of Sir James Frazer’s The Golden Bough led him. Girard read and studied Frazer’s book before his conversion to Christianity. He suspected flaws in Frazer’s reading of mythology and how it contradicted the Bible.

In The Golden Bough, Frazer catalogued all the mythic scapegoats of the ancient stories. But he confused the scapegoating of Christ with the ancient mythical scapegoats. Frazer failed to see that Christ was an innocent victim of scapegoating.

From his murderers’ point of view his death would save the people, as Caiphas said in his unconsciously prophetic utterance. Girard says that Frazer was perfectly right to point to the similarities between the ancient myths and Christianity – in both instances you have a victim who is killed by an entire community. In the ancient myths the victims were eventually seen as gods. In Christ’s case the victim was in fact God incarnate.

But what Frazier didn’t see, which is the simplest thing of all and should convince everybody immediately, if they were honest, that Christianity is very different from mythology – while being the same. It is exactly the same situation but it is very different because Christianity tells you that Christ was innocent whereas all myths tell you that the victim is guilty…. People don’t see that this is the first time in the history of mankind that a myth occurs where the victim is not guilty but innocent, sent by God himself.

Answering why Christ’s death on the Cross is a saving event, Girard explains that

If you read the “mythical” situation the way I do you can see there is something that is not purely human about it. In classical mythology we are offered all these victims and we take them for culprits, and so forth. In the case of Christianity there are a few disciples who say “no, no, He is not guilty”, who maintain to the end that he is innocent. Therefore they say the truth simply. They say a truth which is anthropological before being religious, but which is the same thing.

Girard points out that Christ’s death on the Cross frees humankind from this deep, profound, inescapable and largely hidden cycle of the scapegoating impulse in which his mythologies imprisoned him. Scapegoating in biblical accounts goes back to the story of Cain and Abel and features in many other biblical accounts – for example in the suffering endured by the prophets. Christianity asserts with certainty that it is the only true religion. It tells the truth about man and about God. In an interview with Peter Robinson of Stanford’s Hoover Institute, Girard commented, “Very few people take this statement seriously, as you well know. They should take that literally.” Answering the question as to why don’t they see that Christianity is different, he replies, “They do not want it. Christianity destroys mythology.”

Girard’s rebuttal of Frazer’s errors is complex, the details of which we do not have the space to unravel here. But at the root of it he finds:

That incoherence traditionally attributed to religious ideas … is associated with the theme of the scapegoat. Frazer treats his subject at length; his writing is remarkable for its abundance of description and paucity of explanation. Frazer refuses to concern himself with the formidable forces at work behind religious significations, and his openly professed contempt for religious themes. (This) protects him from unwelcome discoveries.

At the heart of Frazer’s total mis-reading of the passion of Christ is his rejection of the sacrifice at its heart. Girard comments that anyone who tries to subvert the sacrificial principle by turning to derision invariably becomes its unwitting accomplice. Frazer is no exception. “His work in treating the act of sacrificial substitution as if it were pure fantasy, a non phenomenon, recalls nothing so much as the platitudes of second-rate theologians.”

Because of a wilful blindness, Girard alleges, modern thinkers continue to see religion as an isolated, wholly fictitious phenomenon cherished only by a few backward peoples or milieus. And these same thinkers can now project upon religion alone the responsibility for a violent projection of violence that truly pertains to all societies including our own. This attitude is seen at its most flagrant in the writing of Frazer. Along with his rationalist colleagues and disciples, he was perpetually engaged in a ritualistic expulsion and consummation of religion itself, which he used as a sort of scapegoat for all human thought. Elsewhere Girard argued that the historical phenomenon of Christians warring with Christians was not in fact a Christian phenomenon but its contrary.

Girard’s second revolutionary idea is that of mimetic desire, that is desire driven by the impulse to imitate another or the other. Mimesis = imitation. This can be good or bad. In Sacred Scripture there are two short passages which lead us to a consideration of René Girard’s theory. By this theory he potentially de-fangs the pernicious analysis of human desire inflicted on us by Sigmund Freud.

In the third letter of St John we are exhorted,

Beloved, do not imitate evil but imitate good. He who does good is of God; he who does evil has not seen God.

In the letter of St James we are asked,

What causes wars, and what causes fighting among you? Is it not your passions that are at war in your members? You desire and do not have; so you kill.

And you covet and cannot obtain; so you fight and wage war.

Girard identifies a triangular relationship in desire – object, model and subject are the same. In his interview with Girard, Peter Robinson puts this in the simplest of terms: “Serpent, Eve, apple?” Girard accepts this. “Serpent in the memetic theory of desire is an image of the mediator, the one who directs the subject towards the bad desire. The churches, you know, who know what they are talking about, better than most people think, know that example is the key to bad as well as good behaviour. This is what I call mimetic desire.” In the pursuit of illicit desires this is what we call the occasion of sin.

The imitative nature of desire will often lead to conflict, sometimes violent and catastrophic conflict. Mythology warns us of this: Paris desires Helen and makes Menelaus his enemy and the end of it all is the destruction of Troy.

In this reading of our nature and the process of desiring, Girard identifies good and bad desires: good desires leading to human fulfilment, bad desires leading to rivalry and conflict. One of the great classical spiritual books, Thomas à Kempis’, The Imitation of Christ, points us in the direction of God – as all great spiritual writing does, encouraging us to do as St James did.

But as Girard points out, people polarise around objects of desire. This is true even for food, shelter, places where you can live and so on. But because of limited availability, scarcity, conflict ensues. Desire to have what the other has, and which we have no right to have, makes for conflict, envy, aggressive attempts to acquire it.

Gil Ballie, is a lay theologian and one of the leading interpreters of Girard’s thought. He summarises mimetic attraction and its importance in terms of the current crisis in our culture.

We are, he says, in a civilizational crisis, one that is the outworking of anthropological mistakes that have long festered. Increasingly in the history of Western culture, mistakes which we have forgotten or ignored or misconstrued. Among these he lists mimesis, but also “the most essential fact of human existence, namely, religious longing.”

This feature of the human condition is vastly more important than the opposable thumb or the discovery of fire. Our mimetic predisposition cannot be overlooked without catastrophic consequences, nor can its role in mankind’s religious life be discounted. The great question is: how is this religious acuity awakened and thereafter properly ordered? No small number of people have tried to dispense with it as the residue of an earlier stage of human affairs. It is only a matter of time, however, before that religious longing is transferred to ideologies that promise to relieve the boredom of not having a real religion, ideologies that exonerate the violence of their adherents.

Baillie cites a moment in the tragic life of the poet Sylvia Plath which tragically illustrates our emptiness and our struggle to escape from it. He quotes a passage in Plath’s journals where she longs for God and for purpose in her life. In desperation, she toys with the possibility of committing herself completely to some political “cause” with a capital “C,” the violence of which could be justified as a “splurge of altruism.” Countless people today, he says, are doing exactly that. Plath’s final desperate response was suicide.

There is one feature of this quintessential religious longing that must be recognized: it is always mediated. It is awakened by another or others. The entire biblical canon and the history of the Church provide the guidelines for properly channelling this religious longing, and it does so by showing us countless examples of sinners and saints whose lives and legends convey something about how our religious longing might properly be channelled and ordered.

In the final part of this series we will look at Girard’s personal journey and how his conversion and deep religious life brought him and us to an understanding of mankind’s deepest aspirations and how to fulfil them.

About the Author: Michael Kirke

Michael Kirke is a freelance writer, a regular contributor to Position Papers, and a widely read blogger at Garvan Hill (garvan.wordpress.com). His views can be responded to at mjgkirke@gmail.com.