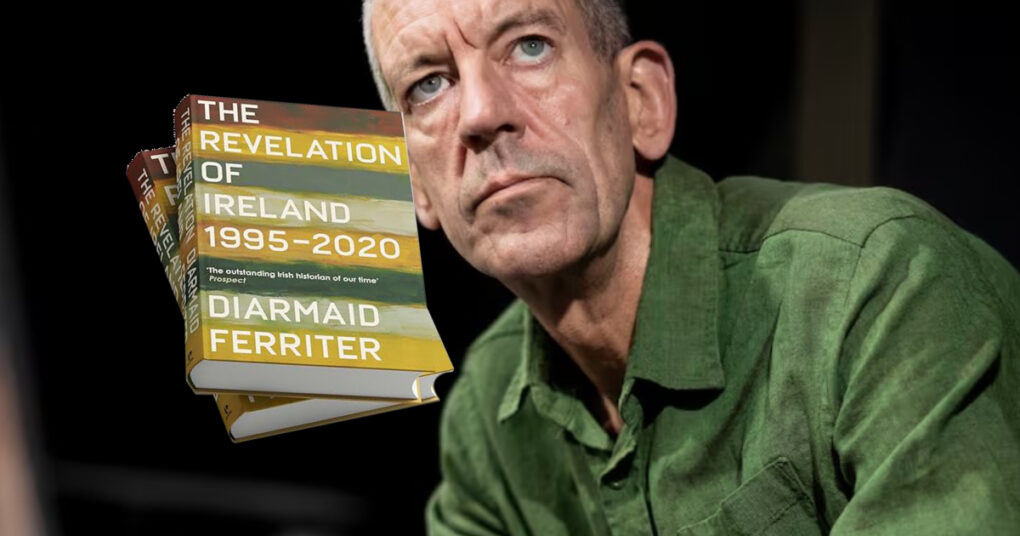

The Revelation of Ireland:

1995-2020

Diarmaid Ferriter

Profile Books

Sept 2025

ISBN: 978-1800810969

Professor Diarmaid Ferriter is as well-known in Ireland for his frequent appearances on the state broadcaster RTÉ as he is for his many history books.

The front cover of his newly-released book, The Revelation of Ireland: 1995-2020 displays a blurb from Prospect proclaiming the University College Dublin Professor of Modern Irish History to be “[t]he outstanding Irish historian of our time.” At times, it appears that some RTÉ producers mistakenly believe he is the only Irish historian of our time. That being said, his overview of recent developments in modern Ireland makes for valuable reading for anyone interested in the economic, political and social transformation of Ireland since the 1990s. As the author explains early on, the book’s “title was prompted not only by what has been revealed about the past, but also how Ireland from the mid 1990s has revealed its potential and its limitations.” Important revelations have included many unsavoury facts about financial impropriety or outright corruption engaged in by Irish leaders.

The first chapter is dedicated to “Political Culture,” and offers a particularly useful summary of developments in a country still blighted by clientelism and the lack of individual accountability in cases of scandal and failure. Although the book is focused on the Republic of Ireland, the ending of violent conflict in the North is addressed comprehensively. By the mid-1990s, the Provisional IRA’s campaign had gone on for a quarter of a century and was accomplishing nothing. Security force losses were minimal by that stage and the Catholic population in Northern Ireland were firmly opposed to further futile violence. Indeed, Ferriter reminds readers that in the 1992 elections, the moderate nationalist SDLP party won more than twice as many votes as Sinn Féin.

The decision by the IRA/Sinn Féin leadership (most notably Gerry Adams and Martin McGuinness) to wind down the IRA’s “war” completely in return for various political concessions was a historic one, but one which has led to historical amnesia setting in on both sides of the Border. This has been ruthlessly exploited by a sinister and destructive party which has profited by swapping guns for ballot boxes. In fact, a recent poll found that 69% of Northern nationalists now believe there was “no alternative” to Provisional IRA violence.

Irish historians deserve some criticism for not highlighting obvious lies when they are told, but the more fundamental problem relates to the Irish public itself: particularly the lack of sympathy for dissenting opinions and the ease with which the entire public can slip into groupthink. Oscar Wilde said that the “problem is the English can’t remember history, while the Irish can’t forget it.”

In recent times, this has been far from true. During the unprecedented economic boom of the 1990s onwards, the government of the day massively increased public spending. A more far-sighted policy would have involved devoting more of this wealth to preparing for the inevitable downturn, which few could have envisioned would have been as devastating as the financial crash of 2008. Ferriter quotes the Finance Minister of this era, Charlie McCreevy, who said that in “a political democracy, it is especially difficult to run any kind of a budget surplus.” Twenty years later, Ireland is again enjoying some of the fastest economic growth in Europe. Tax revenue is booming, and once again, the government is spending massively in the hopes of winning the next general election.

The country’s independent financial watchdog has repeatedly raised its voice in objection and has repeatedly been ignored. Ferriter rightly criticises the excessive focus on wage growth at the expense of long-term planning, but this is far more of a societal failing than a government failing. Hard questions are not asked often enough in Ireland, and there remains a tendency to shoot the messenger instead of considering the message.

Another socio-economic issue which is mentioned by Ferriter but not sufficiently interrogated is the massive increase in the number of women in the workforce from the early 1990s onwards. This stemmed in part from rising prosperity and changes in individual preferences, but it was also due to a government decision to introduce a major disincentive to single-income households within the tax system.

The government’s defeat in the March 2024 referendum aimed at removing from Ireland’s Constitution a reference to women’s “duties in the home” was the cause of some recent outside interest. Realistically however, the referendum meant little. When it comes to the quality of family life and the ability of small children to be cared for in their own homes by one of their own parents, the damage had already been done.

Surveying the history of modern Ireland in these pages, there are occasional reminders that the dominance of the progressive worldview in Irish political life was not nearly so strong until recently. After George W. Bush defeated the Democratic challenger John Kerry in the US presidential election in 2004, the Taoiseach Bertie Ahern said that Bush’s victory had put Ireland “in a stronger position” on economic policy. While today’s Irish leaders are too chastened by the experience of 2016 to publicly state their preference for Kamala Harris, it is safe to say that the expression of sympathy for the Republican Party would today end the career of any mainstream Irish politician.

When it comes to the secularisation of Ireland from the 1990s onwards, Ferriter’s historical account is predictably one-sided. A cursory reference to how Ireland’s development assistance programme was partially inspired by the work of Ireland’s religious missionaries is balanced with a strange remark about the mixing of “religious colonialism and pained emigration”. The role of the Irish Church in charitable services is briefly noted, and some effort is made to consider the role of the Church in the context of broader Irish society.

He is clearly somewhat uncomfortable with the grisly caricature of Irish nuns which is contained in sensationalist portrayals such as the 2002 movie, “The Magdalene Sisters.” At the same time, the record of the famous Cardinal Paul Cullen is simplified in the crudest manner when Ferriter writes that he “had as a common factor in all his exertions obedience to Rome rather than to Ireland” – as if simultaneous loyalty to both was not possible.

Like any history book dealing with modern Ireland, Ferriter’s work is written in the shadow of the greatest such work, Professor Joseph (J.J.) Lee’s Ireland 1912-1985: Politics and Society. Ferriter quotes approvingly Lee’s warning against focusing superficially on the Church’s influence in explaining Irish social trends: “If the nature of Irish Catholicism cannot be ignored in discussing any major question of significance in modern Ireland it is by no means the only factor requiring scrutiny.”

Lee’s 1989 book asked perceptive questions about the record of Irish economic and social failure post-independence, and did not absolve the hierarchy or conservative Catholics from criticism, while still recognising that Catholicism was the “main bulwark of the civic culture”. Other figures are quoted by Ferriter in a similar vein, such as the liberal former Taoiseach Garret Fitzgerald who worried late in life about the impact of secularism in light of the “inadequacy of any alternative lay or civic ethos”. Characteristically, Ferriter includes such observations but does not expand on them. Unlike Lee, Ferriter does little to discomfort himself or his readers, most of whom likely share his basic assumptions about the direction of Irish life. Furthermore, the original insights within this book are overwhelming from sources other than the author.

Another weakness of this work is that the cut-off point of 2020 limits any discussion about how concerns about mass immigration have become a central issue in Irish politics. Ireland first became the destination for large numbers of migrant workers during the Celtic Tiger boom of the 1990s. At first, the immigrants who arrived were mainly Central and Eastern European, with Poland providing a particularly large contingent.

Ferriter includes an interesting comment made in 2007 by the future Taoiseach Enda Kenny, who stated that Ireland was a “Celtic and Christian country,” and added that new arrivals had a responsibility to respect the “cultural tradition” of the host society. His comments were not controversial at the time, and the first waves of large-scale immigration did indeed prove to be very assimilable. What has changed more than anything since then is the origins of those coming to Ireland, including both legal immigrants and refugees. In the first half of 2024, the top five countries for asylum applications in Ireland were Nigeria, Jordan, Pakistan, Somalia and Bangladesh.

It should not be hard to work out why Ireland has finally joined other European countries as a nation where a considerable portion of the public is concerned about immigration. Ireland’s housing crisis is not a sufficient explanation for this sudden change in mood. Multiculturalism worked fine from the 1990s when the multiple cultures were broadly similar to that of the host nation. When the beliefs and attitudes of immigrants are radically dissimilar to what Enda Kenny called the “cultural tradition,” a problem immediately presents itself.

This is yet another revelation of modern Ireland. The country is not that different from the western world, and the recent embrace of Woke progressivism as a substitute for a national identity that was interwoven with Catholicism has not insulated us from the challenges long faced by Britain, France, Germany and many other countries. A braver historian than Ferriter would have the courage to build upon the occasional moments of perceptiveness contained in these pages. He has shown he can do this in his brilliant revisionist book on Éamon de Valera, Judging Dev which was published in 2007.

The Revelation of Ireland 1995-2020 is a worthwhile book for anyone looking for a synopsis of recent Irish history. Those looking to dig deeper will need to venture elsewhere.

About the Author: James Bradshaw

James Bradshaw writes on topics including history, culture, film and literature.