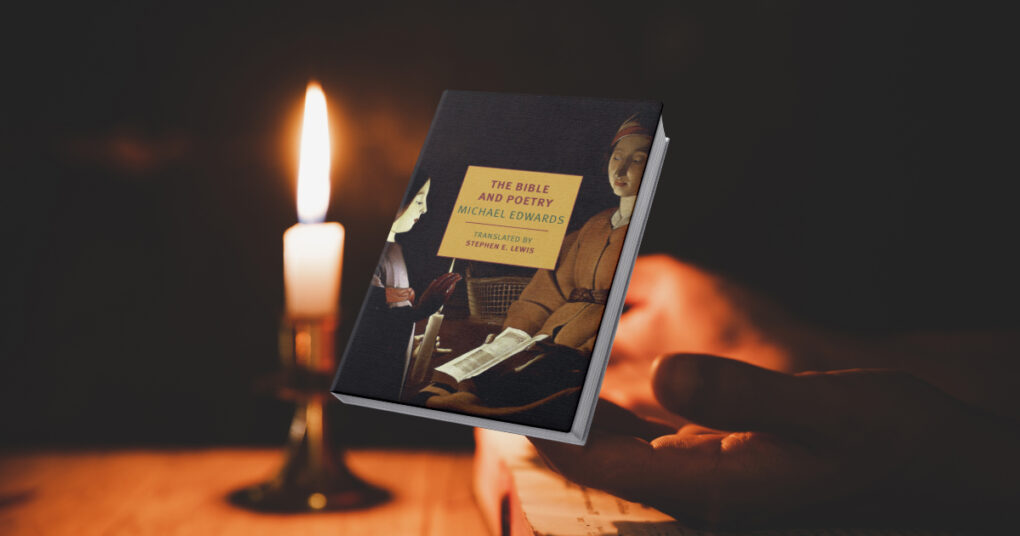

The Bible and Poetry

Michael Edwards

New York Review Books

Aug. 2023

192 pages

ISBN: 978-1681376370

The Bible has been the site of contested readings and meanings for centuries, some reasonable, some less so. In The Bible and Poetry, a literary critic sharpens his pencil and offers his own attempt at understanding this historic and influential text. The book attempts to park theology and instead glean truths from Genesis, Job, Isaiah, the Psalms, the Song of Songs, the Last Supper, and the Gospel of St Luke by appreciating their literary attributes.

Michael Edwards is an English literary critic now based in France. He was Professor of English and Comparative Literature at the University of Warwick for many years, before being appointed to France’s premier research institution, the Collège de France, in 2002. He later became the first English person to take his place among les immortels (as they are known) of the Académie Française, the highly select governing authority of the French language. It is perhaps fitting that this book was originally published in French, and even more fittingly Gallic that a translator was employed to translate it into English (rather than Edwards himself!).

Edwards is a Christian, but he eschews any greater precision than this, and his readings reveal a definite heterodoxy at times. An early chapter relates his own conversion story. As a child, “with no one in my family interested in religion, the subject was never brought up”. Encountering the Bible at nineteen, he had no conceptions (or preconceptions) of Christian doctrine. What he describes as the “otherness of Christianity” and the authority with which the Bible spoke to him, unlike any other text he had read, drew him in. It offered him “a different way of knowing, which I was powerless to bring about myself”.

For Edwards, “I believed, or I believed that I believed, not because the Bible had convinced me by arguments, or by proofs (the Bible doesn’t prove anything), but thanks to the strength of its word, which I now call poetic.” Recalling Blaise Pascal’s description of Christianity as “strange”, Edwards finds resonances with the literary: “poetry is also strange, for it likewise has the task of allowing a glimpse of what transcends us.” The idea of the literary as a channel for the transcendent is not new, but for Edwards it was his path to the faith, and he wants to share some of these glimpses with his readers.

The Old Testament’s Song of Songs is an obvious text to consider for its interplay of literary and theological. Edwards acknowledges “its astonishing poetry, so extravagant and properly Middle Eastern”. He argues that the Song of Songs should be appreciated as “a prolonged play on words, which appears from the very beginning of the poem”. It progresses through a series of concatenating Hebrew word stems. The opening verses, for instance, echo with words such as shelomo (“Solomon”), shemen (“oil”), shem (“name”), yerusalem (“Jerusalem”), and ultimately shalom (“peace”).

An ancient reader or listener would have been attuned to, and appreciated, these rhythmic repetitions in a way that is unavoidably lost in translation to us today. The ancient Hebrews likely “heard writing”, as Edwards memorably puts it, just as countless other societies did at this time. Oral literary traditions have remained strong until as late as the last century or two. In this regard, hearing the playful beats of words such as those above, Edwards posits that “it is poetry that gives […] access to this world of transformation, metaphors and comparisons”. Literary technique is not a frivolous superfluity in the paradigm he articulates, but central to meaning.

The Gospel of St Luke is an example of a New Testament source that can be read for its poetic forms, particularly the Magnificat, or “Mary’s psalm” as Edwards calls it. The hymn presents itself as a “citational poem”, with many of its verses finding “an echo of one or another of the books of the Old Testament”. Mary’s words ring with the words of earlier writers and prophets in her tradition. For Edwards, “it resembles the Anglo-American modernist poetry of T.S. Eliot and Ezra Pound; it departs completely from a certain Romantic idea of authenticity by showing that true emotion can be discovered not so much in listening to one’s own impulses, but instead in opening oneself to the voices of others”.

Mary the romantic and Mary the modernist are certainly peculiar conceptions, but they do afford very literary ways of thinking about her Magnificat. In a sense, her appropriation of the idiom of her forbears throughout the hymn establishes a continuity with the past, even though the event that the Magnificat commemorates – the Incarnation – represents an extraordinary disruption and reorienting of all that has occurred before. These starkly contrasting perspectives converge in the citational character of her poem.

Each chapter offers an interesting reading of some aspect of the literary in the Bible. However, the book is marked by a distinctly anti-theology colouring throughout, which casts a shadow over Edwards’ analyses. Indeed, he devotes an entire chapter early in the book to a reproval of theology’s tendency to quibble and speculate and lose sight of the bigger picture. St John Henry Newman, the great poet, philosopher, and convert of the nineteenth century, is frequently invoked to support Edwards’ claims at this point. Newman, he reminds us, wrote that the Bible “is addressed far more to the imagination and affections than to the intellect”. In its now centuries-long attempts to analyse, categorise, and desiccate, theology, it seems, has gained a somewhat vampiric quality, draining its one source of life and meaning – the Bible – of all its variety and colour.

While it is possible to have some sympathy with Edwards at times, his critique is heavy-handed and, in the end, not convincing. Theology’s indefatigable attempts to define and classify are too stifling for him. “We do not read the Bible as it is meant to be read”, he argues, “theology always risks leading us astray by elaborating its own discourse.” However theology is a practice as much as a corpus of learning, and is ultimately inescapable, even to Edwards. Even as he criticises the totalising claims of theology, he is, in effect, theologising to the reader through his exegeses of some of the Bible’s poetic and literary passages. Even as he criticises it, he cannot help but engage in it. Ultimately Edwards’ attempt to separate so austerely the literary from the theological creates an unhelpful distinction. It is hard to know what he would make of someone like St Augustine, whose writings are very much theological, but who also wrote about Biblical narratives in a literary manner, and whose own Latin prose shimmers with literary skill.

The Bible and Poetry offers a sympathetic and interesting, though at times very heterodox, approach to some of the Bible’s more literary passages. And it does, to some extent, offer a helpful corrective to our modern tendency to construct elaborate systems of knowledge out of categories and definitions. Such reductive measures can fall short when it comes to appreciating the kaleidoscopic richness of the Bible. Indeed many of the writings of antiquity can be at once historical and literary, factual and figurative.

About the Author: David Gibney

David Gibney is a school teacher in Dublin. He holds a Ph.D. in English literature.