Obedience is Freedom

Jacob Phillips

Polity

2022

200 pages

ISBN: 978-1-509-54935-1

In 1984, George Orwell’s famous dystopian novel, the nation of Oceania is bound by three maxims issued by its all-powerful Ministry of Truth: “War is peace,” “Freedom is slavery,” and “Ignorance is strength.” These apparent truths resound everywhere in the lives and worlds of Oceania’s browbeaten citizens, and the reader is left to observe helplessly as the contradictions of doublethink disfigure the dignity of the novel’s characters.

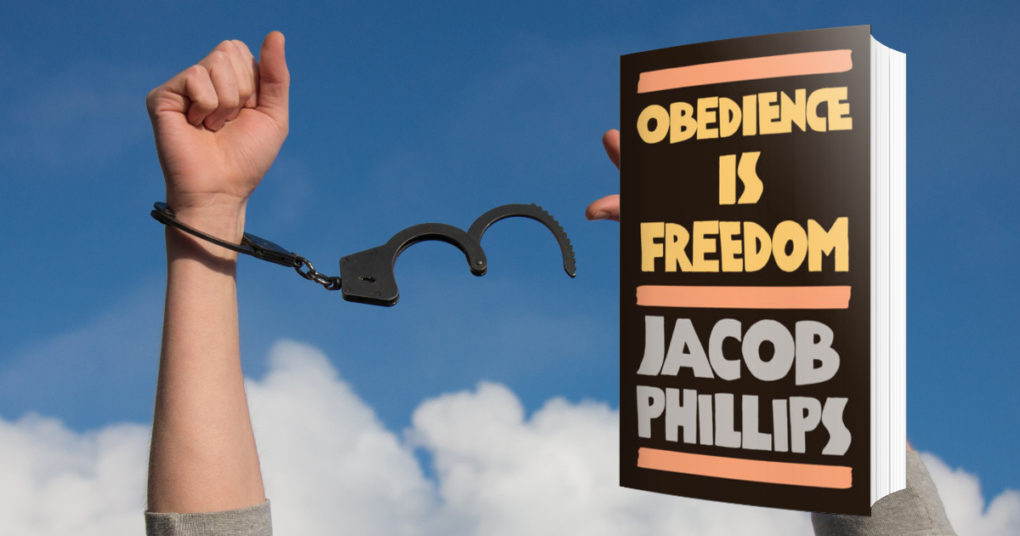

The stark title of Jacob Phillips’ new book, Obedience is Freedom, its words provocatively draping the front cover like a billboard, contains clear echoes of the dark, jarring aphorisms that shape the world of 1984. While Phillips makes no explicit reference to Orwell’s novel, the connection seems unmistakable – except that Obedience is Freedom attempts to express an idea that, however superficially provocative and contradictory, is actually true. Phillips attempts to restore our disfigured dignity by contradicting the contradictions, rethinking the doublethink.

Jacob Phillips is Director of the Institute of Theology and Liberal Arts at St Mary’s University in London. A Catholic convert and theologian by training, he has published on the writings of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, John Henry Newman, and Joseph Ratzinger. Indeed, he was responsible for the English translation of Benedict XVI’s acclaimed Last Testament (2016) autobiography. Behind this polished exterior, however, lies a very colourful and idiosyncratic upbringing.

The son of an anti-war activist mother, the infant Phillips lived for a time in the early eighties at the Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp in Berkshire, a long-running anti-war demonstration against the storage of Cold War missiles at a nearby U.S. Air Force base. An equally anarchic adolescence was spent at raves in rundown dwellings in Brixton, rubbing shoulders with a Dickensian host of characters, from indigent down-and-outs to fashionable yuppies in search of an authenticity their middle class urbanity failed to provide. Phillips vividly recounts his youthful passion for the transgressive sounds of house and techno music in the early nineties, and the grimy London backrooms and pirate radio stations that comprised this scene before its gentrification and mainstreaming a decade later. Many of the book’s chapters open with wonderful and wistful throwbacks to these aspects of the author’s youth, serving as the soil in which his deeper philosophical reflections are rooted.

The book’s title is clearly attention-grabbing. Modern, industrialised society sees a litany of contradictions in media, workplace, school and university pummel the mind of the citizen. The title of Phillips’s book thus submits to the reader’s anaesthetised intellect one final, compelling “contradiction” – that obedience offers freedom. The book sets out to explore how obedience is not servility and how responsibility can free us from ourselves. The possibility that the atomised individual, convinced that they have found freedom in identitarian self-fashioning, might in reality be subsisting in moral and ontological servitude, may prove challenging to the contemporary reader. In this regard, the book forces us to rethink our understandings of concepts such as loyalty, deference, duty, and obligation, by untangling our often superficial awareness of them from their deeper significance. Indeed these terms, among others, comprise the one-word chapter headings of Phillips’ book, carrying over the stark simplicity of the book’s title.

Phillips argues that we erroneously conceive of freedom as “individual self-fulfilment.” Consequently in today’s individualistic cultural and intellectual milieu, ideas such as loyalty, deference, duty, or obligation, mentioned above, will strike many a reader as strident, out-of-place, and entirely contrary to their understanding of freedom. The book consciously leans into these contradictions — what Phillips describes as the “broken binaries” that shape modern life. In the introduction, he describes the book’s modus operandi as “synaesthetic — an attempt to bring together things we cannot imagine being the same.” Such an approach attempts a restoration of life’s broken binaries, so that the reader might perceive in freedom something vastly greater and deeper than personal self-fulfilment.

Some of the book’s best chapters are its most provocative and challenging. For example, the chapter on “Loyalty” teases out ideas that are quite jarring to modern sensibilities and understandings of the concept. The chapter is framed by Phillips’ account of serious, and ultimately fatal, health issues his mother experienced while he was a teenager, which eventually left her housebound and profoundly socially isolated. Phillips recounts the demands it placed on him as he tried to move out and make his own way in life, yet always constrained regarding university and work decisions by his obligations towards his mother. Phillips vividly conveys the almost claustrophobic feeling of love and dependence that attended caring for his ailing mother.

He recalls the seemingly contradictory positions sympathisers took on the matter. On the one hand they would assure him that looking after his mother was “the right thing to do.” On the other hand they would offer advice about “looking after yourself,” not “carrying someone else’s baggage,” and so on. For Phillips, loyalty lies at the heart of this broken binary. The chapter attempts to elide these ostensibly contradictory demands. He writes of caring for his mother: “I needed to be free enough to do what was asked of me by the situation I was in, to be free to stay put. But the freedom of which people spoke was only freedom to make something more of myself, never the freedom to stand in the midst of circumstances I would never have chosen.” The demands produced and advantages gained by living out this kind of freedom radically challenge our contemporary understandings of freedom as individual self-fulfilment. Into this fractured binary that pits desire against duty steps loyalty. According to Phillips, “[t]he freedom to stand alongside others when it goes against one’s own choosing is what it means to be genuinely loyal.”

Developing this further, he argues that our incomplete contemporary understanding of loyalty actually places it secondary to choice — first we decide that we agree with some cause; then we choose to be loyal to it. Drawing on Christopher Lasch’s conceptualisation of “belonging” as something primordial (that is, instinctive or inborn) rather than primitive (that is, crude, undeveloped, or unsophisticated), Phillips applies this to loyalty. Loyalty, in this regard, may be understood as a natural (primordial) inclination toward a healthy acceptance of limit, and not a crudely utilitarian (primitive) act of the will based on merely superficial or self-interested factors. Phillips likens loyalty to the unconditional attachment between a totally dependent infant and freedom-constrained parent. Yet the natural or primordial loyalty between both parties reconciles the broken binary that would otherwise pit desire against duty. Phillips reflects that “[i]n loyalty, people dedicate themselves to things neither beautiful nor even pleasing.” Phillips does not sugar-coat the real and apparent burdens love can bring, be they newborns or dying parents — but also challenges us by not reductively accepting them as mere burdens either. For Phillips, “[t]he obedience of loyalty unleashes people from the captivity of esteeming only what they want to like. The result is a freedom to hold dear to that which it is difficult to love.”

The penultimate chapter, titled “Duty,” deals with the freedoms granted by faith and religious duty. Much of the chapter muses upon the contrasting works of two contemporary writers — Submission, a novel by French author Michel de Houellebecq set in a dystopian near future, and My Struggle, a vast six-volume fictionalised autobiography by Norweigan Karl Ove Knausgaard that painstakingly describes the ordinary minutiae of his everyday life. Phillips finds disorientation and nihilism in Submission, whose apathetic characters act as loci for fleeting, rootless perceptions which ultimately “dissolve into meaninglessness.” Knausgaard’s series, by contrast, for all its excessive detail and monotony, still contains glimpses of hope and struggle — “the human subject still fights battles of seemingly cosmic proportions in the unavoidable duties of everyday life. […] The everyday is still vital, still passionate, still full of things so worthy of being fought for.”

For Phillips, the presence or absence of duty is threaded through the plots and characters of these books. Knausgaard’s writings show how, through the performance of repeated habits, duty helps to form the self in a more indelible and complete way than the fleeting identities of modern self-fashioning. Duties as unassuming as feeding a child, doing the shopping, or prayer steel the self against the corrosive forces of mundanity and indifference. In the fulfilment of duties, Phillips argues, “everyday lives are rendered more literary.”

What is the connection to faith here? Phillips finds our culture’s archetypal duties in religious tradition: “Herein lies the wisdom behind monastic rules of life and the importance of regular practices of prayer for believers. Herein one can also understand moments of what the Catholic tradition calls “heroic sanctity”.” Investing the activities of ordinary life with a sense of duty restores purpose to their fulfilment, and freedom to our fulfilment of them. Grappling with the radical freedom this kind of obedience to duty brings, Phillips turns to fellow convert Sohrab Ahmari’s description of the martyrdom of St Maximilian Kolbe as “a strange but perfect form of freedom.” Ultimately, Phillips argues, we find in duties faithfully done “the most profound freedom, a freedom that comes only from obedience.”

The book is written in the crisp manner one would expect from an academic, yet balanced by the colourful anecdotes and wistful reminiscences that frame each chapter. In one or two chapters, Phillips weaves a compelling opening narrative, but the accompanying argument runs a little thin. Similarly, from time to time, the connection between the argument being made and the title of the chapter could have been made a clearer. These are small shortcomings, however.

Despite the author’s day job as a theologian, philosophical and cultural ideas predominate in the book, and religion features minimally. In this regard, Obedience is Freedom is accessible to those of all faiths and none. Its ostensibly paradoxical yet compelling title is sure to attract readers from all walks of life who finally find themselves stricken by one contradiction too many.