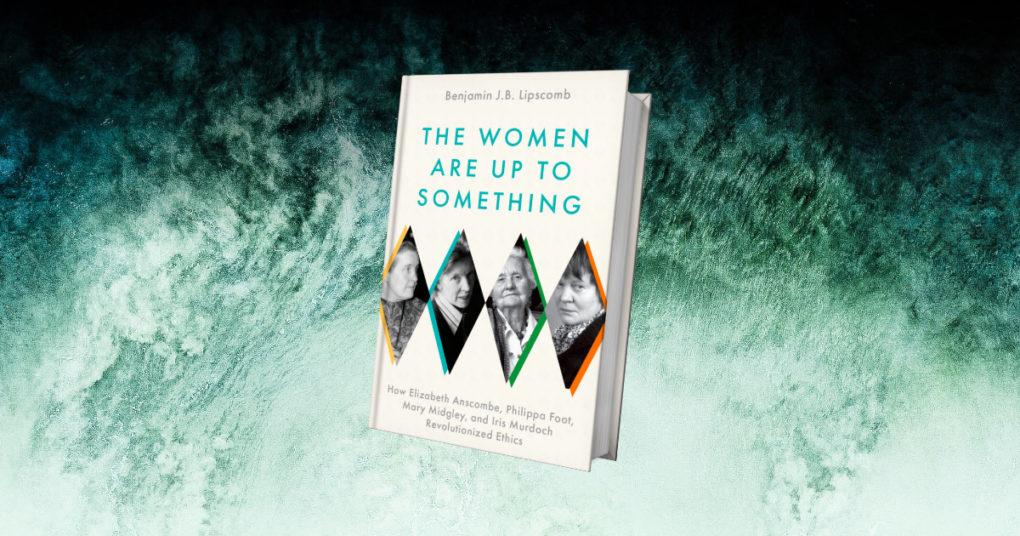

The Women Are Up to Something: How Elizabeth Anscombe, Philippa Foot, Mary Midgley, and Iris Murdoch Revolutionized Ethics

Benjamin J.B. Lipscomb

Oxford University Press

2022

276 pages

ISBN: 9780197541074

The women of the title are the four celebrated twentieth century philosophers, Elizabeth Anscombe, Phillipa Foot, Mary Midgley and Iris Murdoch. They took on the philosophical orthodoxies of wartime Oxford in the post World War II years and the predominantly male establishment who propounded them. What the women “were up to” in the broad sense was challenging the notion that “values can never be facts”, that values are only opinions, preferences, “human projections onto a value-free reality”. The prevailing view in academia at the time was that terms like “good” and “bad”, “right” and “wrong” had no claim to objectivity. The four formidable women would forcibly argue the contrary drawing from the gathering evidence of wartime atrocities in Nazi Germany.

The actual context of the remark “the women are up to something” was more specific of course. It referred to the protest Elizabeth Anscombe organised against the university’s decision to confer an honorary doctorate on US President Harry Truman. For Anscombe and her sister philosophers, Truman was guilty of war crimes in his deployment of atomic weapons against hundreds of thousands of civilians in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. As the world watched aghast in cinemas around the world at emerging film footage from liberated concentration camps, there was an understandable tendency to overlook the questionable decisions of those who defeated Hitler. Anscombe however was too clear-sighted and rigorous in her thinking to overlook moral incoherence and contradiction wherever it arose.

Truman of course got his doctorate and very few stood with Anscombe. She was regarded as the most important among this remarkable quartet of women philosophers both during her lifetime and after. Apart from her intellect, perhaps, the thing that separated her most from her peers was her fervent Catholicism. She was not a cradle Catholic but a convert whose journey to the Catholic Church began as a teenager when she discovered books like G.K. Chesterton’s The Everlasting Man on the shelves of her school library. She did not push her faith perspective on her friends and colleagues whose relationship to the faith was ambiguous though respectful. She directed the brilliant Phillipa Foot to Aristotle’s writing on virtue and vice rather than Thomas Aquinas. Strident in personality and passionate about her faith as she was – she and her husband threw a party to celebrate the publication of Humanae Vitae – she was also, like the best teachers and tutors, sensitive to the worldview of those she engaged with. Aristotle influenced Aquinas. Aristotle could lead to Aquinas. She believed in allowing people to work through what she called their “resistances”. Though she never publicly became a believer, Philippa Foot, was known to read the passion narrative of St John on Good Friday. However Foot, like Iris Murdoch and Mary Midgley based their philosophical thinking on human rationality and what we can learn about ourselves from the sciences of biology, anthropology and psychology “to posit a truly human pattern of life”. For them, ethics was grounded in an informed understanding of human complexity that the sciences reveal and philosophy interprets. That remained the “picture” or background of their research and thought.

The intensely religious Anscombe and her three friends found common ground in asserting the objective nature of evil in energetic opposition to the prevailing dogmas of the academy. Taking on leading defenders of philosophical orthodoxy, like A.J. Ayer, J.J. Austin and Richard Hare, was difficult though facilitated in no small way by Pathé News newsreels from Nazi death camps. For philosophers like Ayer, “ethics was a construction, a creature of words, of language … an artifice”. Across the English Channel, this view was reinforced by French philosopher, Jean Paul Sartre, who believed that we decide, rather than discover, what is important in life. According to Sartre, we invent values in a world where none can be found and our identities are no more than the sum of our choices. For Ayer, the only “ethical” demand that can be made is for consistency in our choices, for acknowledging the implications of our chosen commitments so we can “achieve harmony with ourselves and the world”. Looking back at such positions from the early twenty-first century, where fast emerging, ideological orthodoxies jostle aggressively with traditional religious ones, it is hard to understand how such a confident, subjectivist, relativist view of morality could have held such sway after being confronted with images from Buchenwald and Bergen-Belsen. The intellectual ethos of our own time is more aggressively secular, yet it seems to acknowledge, however incoherently and confusedly, that good and bad, right and wrong have an objective reality.

Lipscomb’s book also reveals how there were other positive and formative influences in Oxford which gave the four young women direction and confidence in developing their thinking. Chief among them was Oxford philosopher and theologian, Donald McKinnon. His influence on Anscombe, Foot and Murdoch was profound and they acknowledged their huge debt to him in effusive terms to the end of their lives. Like Anscombe, he did not push his faith perspective but gently guided his students on their own paths of discovery. He certainly played a key role in the emergence of the four significant female intellectuals in a university that only started awarding degrees to women in 1920 and which still stipulated that the male to female ratio could not fall below four to one. Another forceful formative influence was Austrian philosopher, Ludwig Wittgenstein, whose work absorbed Elizabeth Anscombe, academically and personally. Such was her sense of indebtedness to him that she is buried beside him at her request in Ascension Parish, Cambridge. Through Anscombe, Wittgenstein reached Philippa Foot who too came to revere him too. Unlike McKinnon, Wittgenstein’s attitude to faith was an unsettled thing at best but his thinking nevertheless consolidated Anscombe’s in hers and rooted it even more securely in her Catholic worldview.

The timing of the war favoured the women. It interrupted the studies and careers of many young men and gave the women their chance to flourish in a decimated university. It is also significant that all four came from comfortable backgrounds and had experienced intellectual awakenings growing up. For Anscombe it was books like Chesterton’s. Murdoch’s father is described as a bookish civil servant who doted on his only child. Mary Midgley, like the novelist Elizabeth Bowen, came under the influence of Olive Willis, the renowned, motivational principal of Downe House, a private school for girls. Midgley traces her interest in philosophy to reading a copy of Plato’s dialogues which she came across on the bookshelves in Downe House. Philippa Foot was a daughter of privilege with an American mother whose father was US President, Grover Cleveland. While her parents did not approve of higher education for girls, they allowed their daughter to follow her ambitions.

Whatever way circumstances, opportunities and talents combined, the contribution of these women to philosophy was seminal. They rejected the core idea of a dichotomy between evaluative and descriptive language which denies the reality that “they are inseparable in ordinary human discourse’, or in Wittgestein’s words, “a false picture of language and its relation to the world”. For Wittgestein ordinary speech integrates evaluative and descriptive language. Everyday speech uses words such as “rude” which are both evaluative and descriptive.

There is little evidence that the women’s contribution to philosophy was undermined by their gender even though they resented the sexist irritations that extended from relatively minor offences like being addressed as “Sir” in formal letters to being pointedly ignored by certain prominent academics at formal dinners. In all these instances, the women were able to turn the tables effectively and robustly on their tormentors.

Mary Midgely appears to be the only one of the four who considered how being a woman makes a difference to one’s work. She frankly acknowledged gender differences in approach, method and style. They are the same differences we hear about today from feminists defending workplace gender balance. According to Midgely, women by nature and habit are better at integrative thought or synthesising. They are more conscious of the complexity of their subjects. Men on the other hand are more likely to force data into “a ready made pattern”. They make better specialists, she says. She regards both styles as equal in value. She does not, to be clear, make any argument for gender balance as such but for freedom for both sexes to play to their respective strengths, whether side by side or in separate fields. She herself was a stay at home mother for many years while her children were growing up.

Anscombe’s faith allowed her to close the circle of philosophical enquiry in a way the others failed to do. Acknowledgment that good and evil had an objective as well as subjective reality led one to talk about principles and duties that deployed the vocabulary of a legal system. Such language raises the question of an ultimate authority. For Anscombe, “to fear God and keep his commandments” is where our reasoning takes us in the end if the questions of philosophy are to be resolved. Our freedom to make choices, “to calculate what is best … lies within the limits of that obedience”.

This well written book is a window into the intellectually and socially intense lives of four significant women in British philosophical and literary history, their inter- relationships, family lives, controversies, key mentors and influences along with their respective contributions to the world of ideas. The scope of the book is perhaps too broad. There is a lot that deserves to be more fully unpacked and explored. This is also the strength of the book. It offers fascinating glimpses into many gifted personalities and philosophical perspectives that the reader will want to revisit and explore in more depth and detail. It is the kind of book that makes its readers want to delve more deeply into its subject matter and that really is a good measure of the worth of any book.