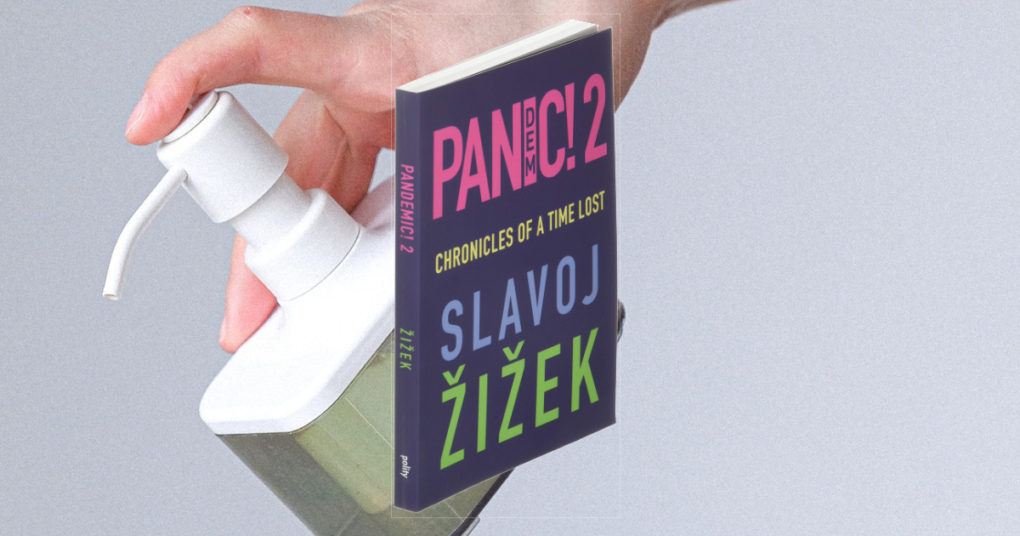

Pandemic! 2: Chronicles of a Time Lost

Slavoj Žižek

Polity

Jan. 2021

208 Pages

Slovenian philosopher, Slavoj Žižek’s second book on the Covid19 pandemic was published in January of this year, some nine months after his first book on the subject. Not a whole lot more was known, publicly at least, about either the pandemic or its likely enduring consequences in January 2021 that was known in March the previous year. We still don’t know about the origins of the virus. We still don’t know how it will mutate. We don’t know if it will continue indefinitely unlike previous pandemics. We certainly don’t know what the lasting effects will be on the economy and societies in general or on the health of those who caught the virus. We do, however, know about something at this point that Žižek didn’t know when he signed off on the book, and that is the development of effective vaccines. That significant game changer is therefore not part of the discussion in Žižek’s second jeremiad and it is hard to say how it might have modified or mollified his gloomy musings.

Pandemic2 makes, if anything, a more trenchant case for radical revolution. “Our world is falling apart.” For Žižek, the Covid crisis compounds the other existential crises of our time, the ecological and climate crisis, the deepening divide between rich and poor and the struggle for racial justice. It is clear to him that our problems “can’t be solved within today’s political and economic systems”. Covid 19, for Žižek is not a stand alone issue the world can deal with separately from the other challenges. He again calls for global solidarity and co-operation and the permanent suspension of “market mechanisms”, in other words, the capitalist system.

He sets out a vision for a kind of utopia, albeit a somewhat frugal one, where everyone would enjoy modest sufficiency. He never considers how wealth will be created to make this vision a reality once the capitalist system is abolished. He dismisses present efforts to eliminate poverty that allow the rich to “stay rich”. But how will a welfare society will be funded without wealth makers? He envisages a single, central bank that “manages money in a transparent way”. There is much about his vision that smacks of fantasy. The implicit trust in human nature to do the right thing, to be always motivated by love of neighbour without any belief in transcendence will raise questions and eyebrows among many readers.

The book, like its predecessor, is not really about the pandemic in the final analysis. It is about the writer’s intense dislike of “the liberal anarchy of commerce” and globalisation which he describes as “post-modern imperialism”. He sees Covid19 as one of the drivers of revolution along with the challenges of climate change and the great reckoning with racism. With the apparent success of vaccinations in driving back the pandemic, Žižek’s pessimism about Covid19 being one “permanent wave” that will be overtaken by even worse viruses, released by melting permafrost as Earth’s temperature continues to rise, is very questionable at this point. It is no more than surmise and premature surmise at that since he did not know how significantly the vaccines would impact the virus’s advance when he was writing his book.

He shows his ideological bias again in presenting the BLM movement as a simple crusade for justice and redress without any taint of a political or ideological ulterior motive. It is Marxist in its founding inspiration as is the climate campaign led by Greta Thunberg, whom he is fond of quoting. These causes are in many ways proxies for far reaching leftist political aims. Žižek harnesses them alongside the Covid crisis to advance his case that the only hope for humanity now lies in a new purified form of communism.

He suggests our understanding of our own nature is linked to the way our society is ordered. When the Church controlled the social order there was an acceptance of hierarchies, sacred and secular, “species and subspecies”. When societies were industrialised and fortunes could be built as well as inherited, human nature was understood in terms of evolutionary struggle, survival or dominance of the fittest, the most diligent, ambitious and talented. With globalization there is a dawning sense that it is only in solidarity and cooperation that we can flourish, both as individuals and communities. Yet, those different understandings of human nature cannot be separated neatly by epoch. The Gospel message is that we are all “one in the Lord”. Divisions along class, gender and ethnic lines were challenged two thousand years ago in St Paul’s resonant lines: “Henceforth, there is neither Jew nor Gentile, neither slave nor free, nor is there male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus’ (Galatians 3:28). In today’s world, all three understandings of our nature can be found and of course they can even overlap. Alongside calls for solidarity and inclusion, there are new hierarchies who seek to ruthlessly clear the public square of those who disagree with them. Some of those who call most enthusiastically for solidarity and inclusion stand at the summit of the new technocratic hierarchy. But Žižek does acknowledge that repression is finding new forms in our age. He deplores cancel culture and political correctness. He doesn’t consider that no revolution has ever succeeded without systematic suppression of free speech, nor does he give any thought in this book to the fact that, in broad ideological terms, the enforcers of new orthodoxies are his leftist, fellow travellers.

Žižek doesn’t see a clear path to revolutionary change. He identifies three fundamental obstacles to the realisation of his vision. Populism, the rise of inward looking nationalism, as embodied by Donald Trump, is probably the most serious obstacle for him from the amount.of time he devotes to it in his book. He finds Trump utterly and irredeemably deplorable, “obscene”, ignorant and, at least potentially, tyrannical. At the time of writing, Trump was still in the White House and Žižek believed he would win a second term. He would have enjoyed writing about the fraught and chaotic period of transition between Trump’s defeat and Biden’s inauguration. Yet, Žižek overlooks the factors that led almost half of the American electorate to choose Trump over Clinton and Biden. He does not consider that for many voters liberal abortion laws are more “obscene” than Trump’s vulgarities, that Trump’s obvious pursuit of personal wealth is not necessarily incompatible with the interests of many working people whose economic conditions improved during his presidency.

Žižek sees the natural human refuge of denial and attachment to “normality” as another obstacle to waking up to our predicament and realising how only radical change will save us. He understands how people, frustrated with numerous restrictions on their freedom, can be susceptible to conspiracy theories and see obligatory masks as an erosion of their personal autonomy and dignity. Even though he finds such behaviour selfish and irresponsible, he sees anti-mask protests as an understandable “politicisation” of the issue. The same might be said about his own books. They too politicise the issue and arguably exploit it to advance his own favoured political beliefs.

More frustrating for him is the third obstacle to revolution which is the substitution of a plethora of identitarian causes for the more key cause of radical economic and societal reform. Rich liberals protect their privileges by identifying and pandering to victim groups, defined by ethnicity, race, gender and sexual orientation. For Žižek, the best protection for victim groups of all types is the social and economic new order he proposes. It is the context within which all the world’s problems around justice, climate, food security and pandemics can be most effectively resolved.

Reading Pandemic2, there is a sense that the world needs healing on many levels. Žižek’s revulsion with manic consumerism and outlandish displays of wealth while millions suffer in dire poverty is something to exercise every conscience. Yet, there are other things he glosses over that are no less troubling. The denial of basic freedoms and rights to millions of people across the globe often because their leaders had a political vision that was supposed to lead them to some sort of utopia.