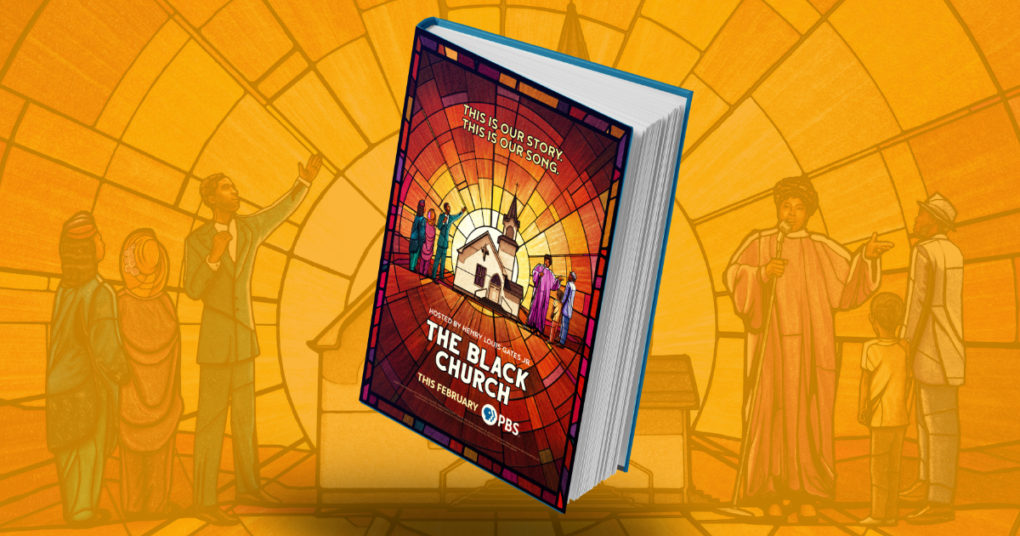

The Black Church: This Is Our Story, This Is Our Song

Henry Louis Gates

Penguin

2021

304 pages

Henry Louis Gates is the Director of the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research at Harvard.

Gates has long been well-known for his writing and television work, and his new book – The Black Church: This Is Our Story, This is Our Song – is a companion to a recent PBS series.

The focus here is on the most important institution in the history of the African-American community – the black church: how it began in the era of slavery, how its unique identity evolved over time and the central role which it played in fighting the long battle for civil equality.

“The black church was the cultural cauldron that black people created to combat a system designed in every way to crush their spirit,” Gates writes. “The miracle of African-American survival can be traced directly to the miraculous ways that our ancestors – across a range of denominations and through the widest variety of worship – reinvented the religion that their “masters” thought would keep them subservient.

“Rather, that religion enabled them and their descendants to learn, to grow, to develop, to interpret and reinvent the world in which they were trapped; it enabled them to bider their time – ultimately, time for them to fight for their freedom, and for us to continue the fight for ours.”

Gates is a gifted writer who tells this remarkable story well, starting with the description of the brutal Atlantic slave trade, and the captives who were transported across the ocean.

Contrary to what some modern-day black Muslim groups suggest, only a small minority of the African slaves were from Muslim backgrounds. Interestingly, many were originally Catholic, as Catholicism had gained many converts in Kongo (Congo) and elsewhere from the 1400s onwards.

Though slave-owners were initially disinterested in converting their slaves to Christianity, over time white missionaries taught a sanitised version of the faith (references to the liberation of the slaves in Exodus were omitted, for instance) while monitoring the slaves’ activities at all times, and preventing them from gaining the literacy skills needed to advance on their own.

Over time however, a measure of self-determination was achieved. The First Great Awakening – a series of evangelical religious revivals which swept the colonies in the 1730s and 1740s – lowered the barriers between blacks and whites, and this charismatic style of worship would have a lasting impact. Over time, ramshackle “praise houses” became the first social institutions which Southern slaves had some control over.

After the Union’s victory in the Civil War, newly emancipated blacks set to work establishing independent churches of their own. In the process, many were able to escape the segregated slave pews of white churches, with the lasting effect being that eleven o’clock on Sunday would become – as Reverend Martin Luther King later observed – “one of the most segregated hours, if not the most segregated hour, in Christian America.”

What was subsequently forged was an extraordinary institution, the unique characteristics of which are still so striking to any visitor who has had the privilege of attending a black church service.

In an environment where literacy rates were still so low, music became an exceptionally important part of Christian teaching and worship, and the Spirituals (or “Sorrow Songs”) which emerged blended white Protestant hymns with West African lyrical traditions, influenced of course by the painful realities of life in segregated America.

Given the difficulties in finding men with formal education to serve as preachers, what was most important was effective and charismatic preaching, which perhaps explains the unrivalled oratorical abilities of the African-American clergy.

Within a racist society, churches were the only places in which black Americans’ true feelings could be expressed, often in emotional terms, and this helps to explain the strong political activism of many black churches to this day – activism which tends to benefit the Democratic Party significantly.

Black churches played a key role in providing education and social services. In time, “The Great Migration” involved millions of blacks moving from the rural South to America’s growing cities, and once again the churches played a crucial role in supporting uprooted families seeking a better life.

Though the population shifted, the importance of the church did not, and slowly but surely material and social progress was achieved. “Black houses of worship would shelter a nation within a nation, gradually becoming the political and spiritual centers of local black communities,” Gates writes. Little wonder, then, that Christian churches and clergy like King and others played a leading role in winning the battle over civil rights in the mid-20th century.

Throughout the book, the author does an exceptional job of describing how the black church came to be, and explaining how important it was and still is. However, he bemoans the theological conservatism of some congregations, and their reluctance to embrace a more liberal social agenda (leaving aside their solidly left-wing views on other issues), without considering why it may not be possible for believing Christians to do so.

Gates’s interest in the black church is more cultural than religious. Only in passing does he address the growing secularism of black America. Though more religious than their white compatriots (a 2018 Pew study found that 79% of black Americans identify as Christian, compared to 70% of whites), the rise of the “nones” is also having an impact here, with younger black Americans much less likely to attend church.

The growing irrelevance liberal Christian churches in America and across the West in recent decades should give pause to anyone suggesting that this is a viable path. In this respect, the relative durability of America’s black church sets it apart, as does the extraordinary history and transformative legacy which Gates outlines to such great effect.