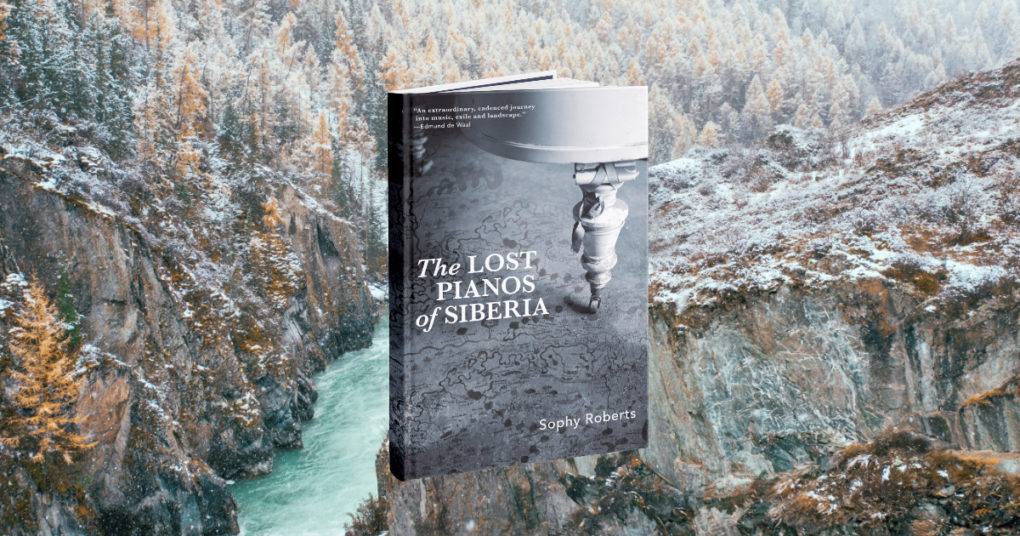

The Lost Pianos of Siberia

Sophy Roberts

Doubleday

2020

430 pages

To adapt the well-known quote from LP Hartley’s novel, The Go-Between, Russia is “another country and they do things differently there.” This has something to do with its immense size, the long, uneasy relationship between its European and Asiatic halves, traditionally divided by the Ural Mountains and – not unrelated to these – the tragedies and upheavals of its unique history. In this, her first book, Sophy Roberts is alive to all that the country represents and, in particular, how a living musical culture is revered and celebrated in the most unlikely places.

Her book has the charm of her unflagging enthusiasm, and her openness to new experiences – however improbable and unusual. She endears herself to readers by the very impulsivity of her plan: “Travelling further and further from my home in England in pursuit of an instrument I don’t even play.” Roberts is honest about her lack of a musical education (unlike, as she points out, the schoolchildren of the old Soviet education system); but what she lacks in formal knowledge of music she compensates for by a writer’s sensitivity to what inspires the musicians, music teachers and piano tuners that she meets in her travels. “I love nothing more than listening to people talk,” she admits as, along with her loyal interpreter, she hunts down families and institutions in remote places on the map, to hear their poignant and passionate stories, their long love affair with their pianos.

The start of Roberts’ unusual search for “lost pianos” began in 2015 when, staying in Mongolia, she met a brilliant young Mongolian pianist, Odgerel Sampilnorov. With sponsorship, she agreed to search for an old, lost, Siberian piano of quality for the musician to play. Of such unlikely beginnings do strange quests begin. And why not search in, of all places, Siberia – perceived by Western readers to be a place of unimaginable remoteness, hardship and exile? After all, as Roberts discovers, “instruments had trickled into this wasteland over the course of three centuries.”

Just enough history is included in the book to provide the background to the search. In 1774 Catherine the Great ordered a new-fangled key board instrument from England, a piano anglaise. In a country desperate to show its Europeanised and civilised aspect, the instrument, and its later evolution into a pianoforte, became immensely popular. By the time pianist and composer, Franz Liszt, with his flowing Romantic appearance and virtuoso playing, gave a sensational concert in St Petersburg in 1842, “pianomania” among the cultivated classes in Russia was well under way; indeed, the city was popularly known as “pianopolis”.

During the Russian Revolution, owners’ pianos were tied on tops of trains fleeing Russia for the Far East and Manchuria. Such was the chaos that in 1919, a St Petersburg music critic sold his grand piano “for a few loaves of bread”. But it was during the nineteenth century that the gradual conquest of Siberia by the piano was achieved. Irkutsk, “the Paris of Siberia” was already flourishing under the deliberate eastern advance of Catherine the Great. An orchestra had been founded there in 1782 and the writer Chekhov, a later visitor, thought it a splendid place, lively with music and theatre.

This, as Roberts relates, had much to do with the aftermath of the Decembrist rebellion of 14 December 1825, when over a hundred aristocrats and army officers were exiled to the region of Chita and Irkutsk by Tsar Nicholas I. What was notable about this exile was that several of the nobles’ wives elected to join them. The most famous of these was Princess Maria Volkonsky who brought culture, music and books to Irkutsk. Ironically, these noble-born exiles discovered that Siberia was a freer society than western Russia; its peasants had no history of serfdom and “better understood the dignity of man and valued their rights more highly”, as one Decembrist recorded.

Later, in 1830 and 1863, thousands of aristocratic Poles were similarly exiled, bringing their own high musical culture with them to Tomsk and its surrounds. Roberts meets an alumna of the Tomsk music school, a concert pianist and music teacher called Olga Leonidovna, who has her own special piano, an 1896 Bechstein (not the least of the book’s interesting byways is the way Roberts traces the serial numbers and later history and fortunes of pianos made by famous piano manufacturers). Olga tells the author that “the Bechstein is kind, noble and demanding. It has a kind of magic.” This language is echoed by others she meets; the music evoked on these much-loved instruments is inextricably bound to the harsh lives led by their owners. On the gravestone of the pianist Vera Lotar-Shevchenko in Akademgorodok, the Soviet “science city”, is the legend: “Life in which there is Bach is blessed.” And in Kamchatka, by the Pacific, the pianist Vasily Kravchenko, whose father died in the Great Patriotic War (World War II), relates that “Whenever I play Chopin’s Nocturne No 13, opus 48, I devote it to the father I didn’t know. It is impossible to get rid of the past.”

Unlike many travel books with scant cartography, Roberts knows readers have to navigate their way through the outlandish places she visits. Thus, each chapter opens with a map of the particular area she is concentrating on, including Khabarovsk – “about as far from home as I could get while remaining on this planet” — Tobolsk (the old capital of Siberia), Kiakhta (now in decline), Novosibirsk (which has the largest opera house in Russia and a Steinway grand, loved by a three-generation family of piano tuners) – even Sakhalin Island, famous from Chekhov’s visit, where Roberts finds “love and humanity – in the last house at the end of the last street at the dead end of Russia.”

As I have indicated, Roberts never loses sight of the forlorn historical resonances of this most evocative expanse of land, writing “I knew that however hard I wanted my piano hunt to celebrate all that is magnificent about Siberia, much of what I was looking for was tied up with a terrifying past.” It is not just in the past, either; the news that the brave Russian dissident, Alexei Navalny, has been sentenced to time in a “penal colony” – though not in Siberia – reminds readers that modern Russia is still a country of extremes: the heights of cultural beauty alongside the depths of practical brutality.

Roberts’ book, combining history, travel, strange stories of survival, many memorable encounters and a wealth of photographs, has much to recommend it.