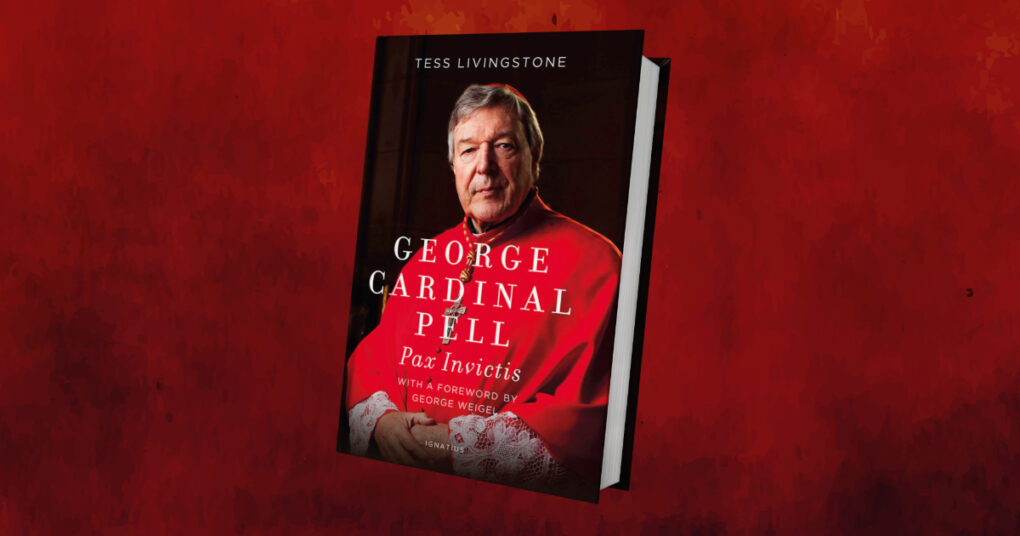

George Cardinal Pell: Pax Invictis – A Biography

(Second Edition of George Pell: Defender of the Faith Down Under)

Tess Livingstone

Ignatius Press

Nov. 24

525 pages

ISBN: 978-1621646570

‘For the reasons to be given, it is evident that there is a significant possibility that an innocent person has been convicted because the evidence did not establish guilt to the requisite standard of proof.’

These damming and profound opening lines come from the 43-page judgment in Pell v the Queen – the decision of the High Court of Australia which acquitted Cardinal George Pell of five historic sexual offences, and in doing so, corrected one of the gravest injustices in Australian legal history.

In Cardinal George Pell: Pax Invictis (‘Peace to the Unconquered’) Tess Livingstone, a longtime friend of the late Australian prelate and correspondent for the newspaper The Australian presents a compelling, definitive and deeply personal account of one of the most controversial and misunderstood figures in the contemporary Catholic Church.

In this updated edition of Livingstone’s earlier 2002 biography published before Pell was made a Cardinal, Pax Invictis – words taken from an inscription on a Melbourne war memorial that Cardinal Pell had long admired, begins with Pell’s death and funeral, which becomes the backdrop for the book.

Of Cardinal Pell’s funeral, Livingstone writes:

‘Through tears, inspiring music, gentle humour, and spontaneous outbreaks of applause, some in the vast congregation in Saint Mary’s Cathedral at his funeral Mass came to know George Pell as never before.’

The stories in the homily by Archbishop Anthony Fisher, the tributes by the Cardinal’s brother, David Pell and the eulogy of former Australian prime minister Tony Abbott were telling. They told of man who fought to ensure indigenous youth were included in World Youth Day 2008 and his making friends at David’s Place, a centre for the homeless in Sydney’s suburb of Rushcutters Bay, to his washing his socks in the shower, putting his jumpsuit on backwards, and sweeping the area outside his cell so that he could hear the birds sing during his 404 days in jail.

The reader is treated to a powerful narrative of a man whose life came to be defined not only by high ecclesiastical office and theological commitment but also by profound personal suffering and public vilification.

This much expanded version covers the many significant events that took place over the past twenty years of Pell’s life, including what Livingstone describes as his ‘huge’ work for the Vox Clara committee that helped guide the new English translation of the Roman Missal and his creation of the Domus Australia chapel and guesthouse in Rome that became one of his ‘favourite places’ in the Eternal City.

Not until Chapter Five do we start on the more conventional biographical content, starting with Pell’s origins as the son of a ‘mixed’ marriage between a devout Irish Catholic woman and a card-carrying Church of England Ballarat publican. The reader learns of his early years in southern Australia as the son of a pub landlord when he aspired to be a professional Aussie Rules Football player, as well as his formative time studying at Oxford and the Pontifical Urbaniana University in Rome.

Livingstone writes in detail about the well-known and pivotal role the Cardinal played in reforming Vatican finances, including the many challenges he faced in the process, and the suffering he endured on account of a much-publicised miscarriage of justice in Australia that saw him spend 404 days in jail in 2019 and 2020 on false accusations of historic child sex abuse.

Within both the ecclesiastical world (both Rome and Australia) and secular Australia, Pell’s clarity of conviction and forthrightness were often unwelcome. He was not a man to dilute doctrine or hedge his bets to appease contemporary fancies. As a result, his presence was often polarising, his voice dissonant in a culture increasingly suspicious of moral certainties. Livingstone portrays him not merely as controversial but as someone who, like Athanasius in a different age, stood Georgius contra mundum – against the world – when conscience and conviction demanded it.

Coming from a family that ran a small business, ‘he was very savvy with money,’ Livingstone writes, and that made him a natural choice to lead the Vatican’s financial reform. (Before Francis appointed him to that role, Benedict XVI had already tapped him early in his pontificate to be a member of a key Vatican financial committee).

When he arrived at the Vatican to lead the reform in 2014, Livingstone writes that he fully subscribed to Francis’ goal of a Church to help the poor – but not Francis’ wish for a poor Church. What he wanted was ‘a better-managed Church’ and his priority was for the Church’s finances to be used primarily for charity and for the poor rather than wasted on unnecessary bureaucracy. ‘He went in with a view to sort it out, to bring modern standards to the place – it was not an unreasonable idea, and initially it went well.’

Cardinal Pell’s successes in reforming Vatican finances provoked fierce resistance from old-guard Vatican officials who had Francis’ ear. That internal opposition led to suspicions of collusion between anonymous figures in the Vatican and Australia to get him out of the way.

Livingstone documents that, already in 2013, over a year before Cardinal Pell came to the Vatican to begin his work on financial reform, the Cardinal was the target of ‘Operation Tethering,’ an investigation Australia’s Victoria police had launched into the Cardinal without any specific allegations against him at the time.

This sense of principled isolation which Pell endured became especially evident during his tenure in Rome. In 2014, Pope Francis appointed Pell to the newly created role of Prefect for the Secretariat for the Economy. It was a bold move, signalling an intention to reform the labyrinthine and opaque financial operations of the Vatican. Pell was chosen precisely because he was not part of the curial old guard – he was an outsider with the moral authority and managerial competence to confront corruption head-on. Francis himself had presented as a reformer, and Pell believed he would have the Pope’s full backing.

But as George Weigel notes in his foreword to the book, that support soon proved uneven. Pell chose to act swiftly and decisively, preferring to make progress rather than curry favour. ‘Putting the pedal to the floorboard,’ he launched initiatives that quickly met resistance. And while Francis had appointed him in part for this very determination, the Pontiff later took steps – perhaps unwittingly – that empowered Pell’s opponents and eroded his authority. Pell found himself increasingly isolated, neither fully embraced by the entrenched Curia nor by the informal papal inner circle that emerged under Francis.

Livingstone’s account paints a portrait of a man abandoned by many of those he sought to serve. In Rome, the betrayal came from within the very institution to which he had devoted his life; in Australia, it came from a public and a legal system that seemed determined to see him fall. Despite this, Pell remained unwavering. Livingstone depicts a man of granite principle, resilient under extraordinary pressure, and ultimately vindicated – albeit at great cost.

Importantly, Pax Invictis does not merely dwell on Pell’s suffering. It offers a rich account of his contributions to Catholic education, seminary formation, and doctrinal clarity. Livingstone devotes significant space to his often-overlooked achievements in educational reform, showing that Pell was far more than the caricature of a reactionary culture warrior. He was imaginative, effective, and deeply committed to the formation of future Catholic leaders. When it came to seminaries, he was bold and sometimes divisive – but his divisiveness arose from principle, not ego. Divisiveness, as the Gospel reminds us, is not in itself a vice.

His concerns about the state and direction of the Church were no secret. In Pax Invictis, Livingstone unpacks the famous ‘Demos’ memorandum, published in March 2022, that was highly critical of Pope Francis and the Pontificate in general. She reveals it was partly composed by him but was a group effort, adding that his beloved uncle, Harry Burke, used to write to newspapers using the Demos pseudonym.

The legal saga that consumed the final years of Pell’s life is, inevitably, a central theme of the book. Livingstone devotes the attention it deserves to the grotesque miscarriage of justice he suffered. The prosecution’s case was thin to the point of incoherence, and the eventual unanimous decision of the High Court of Australia to quash his conviction was not only a personal vindication but a moment of institutional redemption – for the High Court, at least. The same cannot be said for the Victoria Police, the Crown prosecutors, or the majority of the Victorian Court of Appeal, whose errors Justice Mark Weinberg, in his lone dissent, exposed with clarity and courage.

Victims of clerical sexual abuse were among the collateral victims of this debacle. The Pell prosecution, far from honouring them, used their suffering as a pretext to scapegoat a man who had long worked to strengthen safeguarding measures and address past wrongs. The legal machinery became fixated not on justice, but on vengeance – or perhaps optics. As Livingstone makes clear, the determination to ‘get Pell’ ultimately undermined public trust in due process.

A helpful companion to Livingstone’s biography is Fr Frank Brennan SJ’s Observations on the Pell Proceedings (2021), a concise but devastating critique of the legal case brought against Pell. Brennan, a lawyer, Jesuit priest and a sterling social justice advocate with a long record of disagreement with Pell, offers a model of principled dissent. His analysis, grounded in both legal rigour and Christian charity, confirms the central insights of Livingstone’s work. Brennan reminds readers that justice must be blind to partisanship and immune to mob pressure – lessons that were ignored to tragic effect in the Pell affair.

Livingstone recounts an observation made in 2010 by Pell’s old friend Cardinal Francis George of Chicago: ‘I expect to die in bed, my successor will die in prison and his successor will die a martyr in the public square. His successor will pick up the shards of a ruined society and slowly help rebuild civilization, as the church has done so often in human history.’

It was that rebuilding, of Church and civil society, to which Pell heavily devoted his life.

Livingstone’s admiration for Pell is clear throughout, and while the biography occasionally borders on the hagiographic, it serves as a much needed corrective to the malicious and partisan portrayals that have dominated much of Australian media coverage – most notably the 2018 hatchet-job, Cardinal: The Rise and Fall of George Pell by Louise Milligan which itself was made redundant when Pell was acquitted.

Ultimately, the Pell who emerges from Pax Invictis is a figure both lion-hearted and lamb-like: courageous, steadfast and willing to suffer rather than betray his conscience. His life, as Livingstone presents it, is a vivid reminder to all of us of the cost of Christian fidelity in a world that often rewards compromise and punishes clarity.

The biography does not claim to be definitive, nor does it pretend to perfect objectivity – but it does something perhaps more important. It bears honest witness to a man who stood firm in the face of hostility, who bore injustice with dignity, and whose legacy demands to be taken seriously. At times, I found myself genuinely moved and thinking to myself, why and how could this great man suffer so much? Yet, much like his close friend, the late Pope Benedict XVI – he was an extraordinary but totally misunderstood man.

For all his achievements, of which there are many, Cardinal Pell’s greatest triumph will be that he kept his faith, in circumstances which he must have felt like screaming ‘Eloi Eloi lama sabachthani!’, not to succumb to anger, self pity or despair – when almost any other human would – but instead to have accepted this modern day crucifixion, walking humbly in the footsteps of Our Lord. That’s the heroic virtue that makes him, to me and so many others, a saint for our times.

About the Author: Gerard Scullion

Gerard Scullion studied law at Queen’s University Belfast and Trinity College Dublin and is a trainee solicitor based in Belfast. He writes periodically on the role of religion within law and diplomacy.