Science fiction has a respectable pedigree stretching from, by general agreement, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, through Jules Verne, H.G. Wells, and into the mid-twentieth century with Isaac Asimov, Arthur C. Clarke, and others. It’s certainly a robust genre. While that mid-century flourishing may be considered a golden age, some now argue we are in a new golden age.

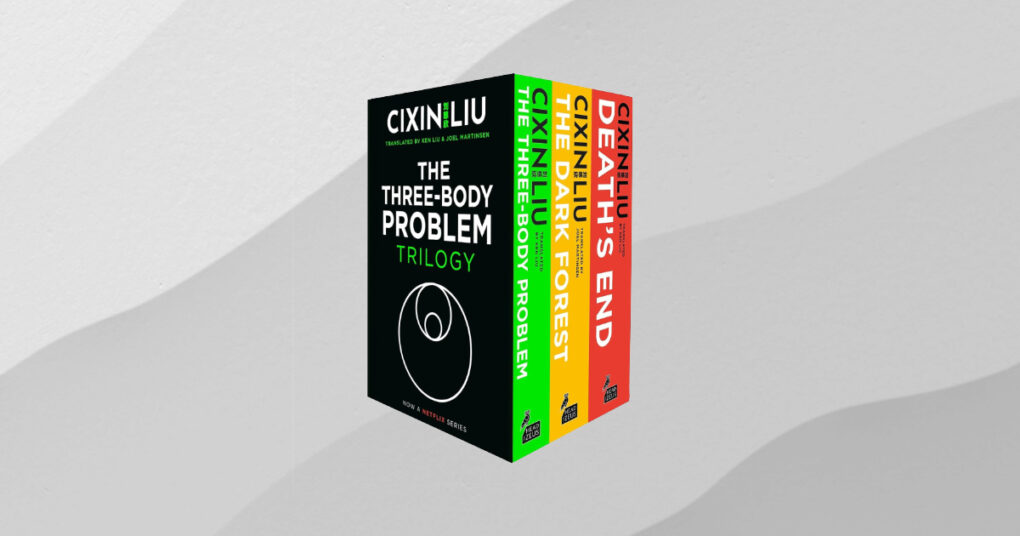

At the heart of this golden age is the Chinese writer Cixin Liu. His fascinating and bewildering – in the best possible sense – science fiction now occupies a sizeable amount of space in the sci-fi sections of most bookshops. His voluminous imaginative works, replete with scientific, cosmological, and astronomical detail, have been translated into more than twenty languages. His most famous work, the epic trilogy Remembrance of Earth’s Past, has sold some eight million copies worldwide.

The timeline of the trilogy spans the present and eighteen million years into the future. The London Review of Books has called the trilogy ‘one of the most ambitious works of science fiction ever written.’

The first volume, The Three-Body Problem, grapples with the threat to Earth from a rival civilization in the solar system on a planet called Trisolaris. This highly advanced civilization’s existence is threatened by the three-body problem, a classic issue in orbital mechanics caused by the unpredictable motion of three bodies under mutual gravitational pull, first posed by Isaac Newton. Cixin Liu vividly imagines the chaos this causes in the lives of Trisolarans, ultimately provoking their plans to conquer and destroy Earth’s civilization.

Earth temporarily copes with the threat, establishing a deterrent based on mutually assured destruction, forcing the Trisolarans to share their technology. This mirrors geopolitical strategies.

As the trilogy progresses, the threat from Trisolaris becomes a sideshow, and it emerges that a vast Dark Forest – the second volume’s title – of alien life threatens the existence of all the universe’s civilizations. The dénouement comes in the third volume, Death’s End.

Cixin Liu’s profile expanded exponentially in 2024 when Netflix launched its ten-episode series based on The Three-Body Problem (Netflix series). The second volume, The Dark Forest, is in production and will be streamed in 2026.

This event provoked speculation about the novel’s geopolitical significance. Does Trisolaris represent the United States and the threat it poses to China, or vice versa? Alternatively, it might be read as a battle between the technological giants of the twenty-first century. A more intriguing aspect of the trilogy, however, is what it reveals about the question of the existence of God within modern, supposedly atheistic Chinese culture.

Authors dislike their work being reduced to simplistic interpretations, and Cixin Liu is no exception. “The whole point is to escape the real world!” he said, not to comment on history or current affairs. He aims to tell a good story. He succeeds, but he also does more.

His story, despite his claims, is grounded in real events. The Three-Body Problem features the horrific murder by the Red Guards of the protagonist’s father, a reaction central to the plot.

In another passage in Death’s End, Liu seems to be potentially commenting on his country’s history. The death sentence of a character deemed responsible for the pragmatic destruction of an outlying planet and its population is debated, prompting a discussion on the morality of capital punishment:

“What about more than that? A few hundred thousand? The death penalty, right? Yet, those of you who know some history are starting to hesitate. What if he killed millions? I can guarantee you such a person would not be considered a murderer. Indeed, such a person may not even be thought to have broken any law. If you don’t believe me, just study history! Anyone who has killed millions is deemed a ‘great’ man, a hero.”

We might ask who Liu has in mind.

A young scientist, Cheng Xin, becomes pivotal in Death’s End and represents the moral heart of the story. Jiayang Fan, a staff writer at The New Yorker (TNY), met Liu in Washington during his receipt of the Arthur C. Clarke Award. Her interview, published in TNY’s print edition of June 24, 2019, titled “The War of the Worlds,” describes an episode where Earth faces destruction. Cheng Xin encounters schoolchildren as she and an assistant prepare to flee. The spaceship can carry only three children, and Cheng, embodying Western liberal values, is paralyzed by the choice. Her assistant poses three math problems, ushering the quickest three children aboard. Cheng stares in horror, but the assistant says, “Don’t look at me like that. I gave them a chance. Competition is necessary for survival.”

The crisis is averted, and all children survive. The episode underscores the trilogy’s moral dilemma. As Fan notes, characters employ Machiavellian game theory and bleak consequentialism. Idealism is fatal, and kindness an exorbitant luxury. A general states, “In a time of war, we can’t afford to be too scrupulous. Indeed, it is usually when people do not play by the rules of Realpolitik that the most lives are lost.”

Cheng rejects this ethic, dodging actions with lethal consequences. Her sense of responsibility dominates. Near the end of Death’s End, she writes her apologia pro vita sua:

Later, my responsibilities became more complicated: I wanted to endow humans with lightspeed wings, but I also had to thwart that goal to prevent a war…

And now, I’ve climbed to the apex of responsibility…

I want to tell all those who believe in God that I am not the Chosen One. I also want to tell all the atheists that I am not a history-maker. I am but an ordinary person. Unfortunately, I have not been able to walk the ordinary person’s path. My path is, in reality, the journey of a civilization.

This is the final reference to God, but not the first. Several atheist characters, in crises, wish they weren’t atheists. Luo Ji, in The Dark Forest, tearfully hates his atheism after parting with Shi Qiang. Dongfang Yanxu, in a low voice, prays despite her atheism, saying, “No, this can’t be happening,” in response to her earlier “god” exclamation. A scientist opts for Pascal’s wager:

“I believe, not because I have any proof, but because it’s relatively safe: If there really is a God, then it’s right to believe in him. If there isn’t, then we don’t have anything to lose…”

When a spaceship seeks a habitable planet, envisioned as a new Garden of Eden, rivalry emerges. An occupant asks, “Will what happened in the first Garden of Eden be repeated in the second?” Another replies, “The snakes of the second Garden of Eden are even now climbing up people’s souls.”

Long-term hibernation enables scientists to work across centuries. Civilizations experience decadence, provoked by hopelessness. Luo Ji and Shi Qiang emerge from hibernation into a licentious orgy:

“Are those people?” Luo Ji asked in wonder.

“Naked people. It’s a tremendous sex party, with more than a hundred thousand people, and it’s still growing.”

Acceptance of diverse relations shocks them, reminiscent of biblical dissolution before the Ten Commandments. Shi Qiang asks why the government doesn’t intervene, but the mayor notes it’s legal, and police are powerless.

Liu seems to reference contemporary mores. In a climactic sequence, Luo Ji digs his grave as doomsday looms, feeling an enormous hand pressing down, then withdrawing as a missile veers toward the sun, averting destruction. This may evoke Ps. 143:7: “Put forth thy hand from on high, take me out, and deliver me from many waters: from the hand of strange children.”

In Death’s End, Cheng Xin faces a mission critical to humanity’s survival. Crowds urge her to accept. A young mother hands her a baby, saying, “Look, she’s like Saint Mary, the mother of Jesus! Oh, beautiful, kind Madonna, protect this world! Do not let those bloodthirsty and savage men destroy all the beauty here.”

About the Author: Michael Kirke

Michael Kirke is a freelance writer, a regular contributor to Position Papers, and a widely read blogger at Garvan Hill (garvan.wordpress.com). His views can be responded to at mjgkirke@gmail.com.