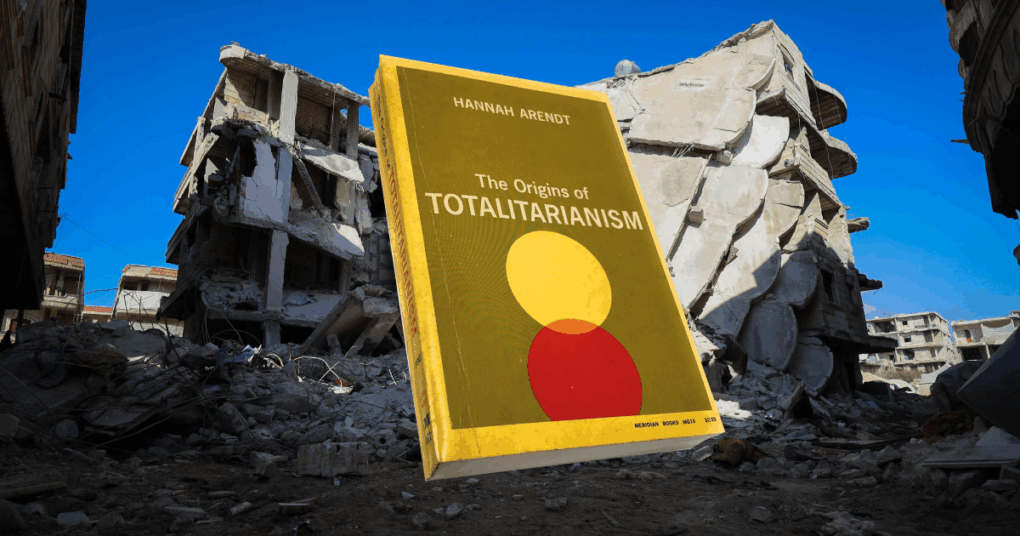

Undoubtedly, one of the most important books written in, and left to us from, the twentieth century was and is Hannah Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism. Why? It is a thorough and spellbinding work on the two-century unfolding of that nightmare of butchery and twisted deceit. It is also a deep and penetrating work of political philosophy which serves as a frightening and lasting reminder that humanity is permanently threatened by the destructive seeds from which that cancer grew. She reminds us that it could happen again.

Predictions are of little avail and less consolation, she writes, but goes on to say that there remains the fact that the crisis of our time and its central experience have brought forth an entirely new form of government – totalitarianism. In 1966 she held that this, as a potentiality and an ever-present danger, is only too likely to stay with us from now on, just as other forms of government which came about at different historical moments and rested on different fundamental experiences have stayed with mankind regardless of temporary defeats – monarchies, republics, tyrannies, dictatorships and despotism.

Nearly sixty years later, with the evidence we have of totalitarian tendencies in our public life, we are hardly in a position to dispute her assertion.

Arendt began writing her study of the origins of totalitarianism as early as 1945. One incarnation of that catastrophic horror had just been eliminated at the cost of a terrible war. Another was still exercising the full force of its tyranny, while the third was about to begin its reign of terror in the far east. The first to be vanquished was that which had spread across Europe from Nazi Germany; the second was Stalin’s soviet empire with its multiple puppet satellites in eastern Europe; the third was the People’s Republic of China with its overcooked clones, North Korea and Vietnam. That one is still with us, carefully camouflaging itself in an attempt to make us think that it is not what it really is.

We think of all these aberrations as twentieth-century phenomena. Arendt’s great and prophetic work shows us, however, that their origins go back through a century and a half of mankind’s confused reading of our world, human society and the many deadly turnings which political thought took over that period.

Yuval Levin’s book, The Great Debate: Edmund Burke, Thomas Paine, and the birth of right and left, is a study of the arguments between Edmund Burke and Tom Paine in the 1790s. In it he showed how the critical divergence in Western political thought in our own time dates from then. That debate was essentially over the foundations on which the rights of man are based. In many ways it matches Arendt’s own vision of where our twentieth-century nightmare started. If we want a dramatic symbol for the turning point which led us to the disasters of our time, we might take the enthronement of the goddess of reason on the high altar of Notre Dame de Paris. This was the symbolic and fatal moment when man was declared to be the centre of all things.

I could not hope and would not dare to try to offer a succinct summary of Arendt’s masterpiece, all six hundred and ten pages of it. The best I can do is explain that in the three parts of her study – the first edition was published in 1951, later revisions in 1966 – the phenomena she holds to account for the world’s greatest catastrophes and the political impasse she saw in the cold war in the 1960s are antisemitism, imperialism and totalitarianism which they spawned.

Arendt died fifty years ago (1975). The chilling thing about everything in her work is that she speaks to our world today in so many ways. One of the great evils which she saw in her time and which, in her view, contributed to the despair on which totalitarianism nurtured itself, was loneliness. She noted that totalitarian regimes fostered the atomisation of individuals in society. Loneliness accompanied this, which, along with distrust of others, fostered the semi-worship of the all-powerful deadly state systems which the twentieth century had to suffer.

What is one of the tragic human maladies of which twenty-first-century men and women have again become painfully conscious? Loneliness.

She wrote in 1966, reflecting on the deadly attraction of the so-called intelligentsia to this new state system, “What’s more disturbing to our peace of mind than the unconditional loyalty of members of totalitarian movements, and the popular support of totalitarian regimes, is the unquestionable attraction these movements exert on the elite, and not only on the mob elements in society. It would be rash indeed to discount, because of artistic vagaries or scholarly naïveté, the terrifying roster of distinguished men whom totalitarianism can count among its sympathizers, fellow-travellers, and inscribed party members.”

The dominant elites of the past thirty years may not have been consciously totalitarian, but the antisemitic mobs which occupied university campuses or London’s streets over the past two years did not come out of thin air. Do her reflections on the power and influence of the elites of her own time not sound familiar to us relative to the cancellations, no-platforming, silencing and destruction of freedom of speech in our time – not to mention their insane efforts to redefine and obliterate our very understanding of human nature?

Furthermore, she explained, this attraction for the elite is as important a clue to the understanding of totalitarian movements as their more obvious connection with the mob. It indicates the specific atmosphere, the general climate in which the rise of totalitarianism takes place. It should be remembered that the leaders of totalitarian movements and their sympathizers are, so to speak, older than the masses which they organize, so that chronologically speaking the masses do not have to wait helplessly for the rise of their own leaders in the midst of a decaying class society of which they are the most outstanding product.

The ultra-progressive capture of our academic institutions is now providing the elders of the movement. Over a few decades, this is what has generated the mobs of young people who in the past decade have torn apart whole city districts and occupied campuses today.

Reflecting on what prepares men for totalitarian domination in the non-totalitarian world, she argues, “The fact that loneliness, once a borderline experience usually suffered in certain marginal social conditions like old age, has become an everyday experience of the ever-growing masses of our century.”

The merciless process into which totalitarianism drives and organizes the masses looks like a suicidal escape from this reality. The “ice-cold reasoning” and the “mighty tentacle” of dialectics which “seizes you as in a vise” appears like a last support in a world where nobody is reliable and nothing can be relied upon. It is the inner coercion whose only content is the strict avoidance of contradictions that seems to confirm a man’s identity outside all relationships with others. It fits him into the iron band of terror even when he is alone, and totalitarian domination tries never to leave him alone except in the extreme situation of solitary confinement.

She explains how the process works by destroying all space between men and pressing men against each other; even the productive potentialities of isolation are annihilated; by teaching and glorifying the logical reasoning of loneliness where man knows that he will be utterly lost if ever he lets go of the first premise from which the whole process is being started, even the slim chances that loneliness may be transformed into solitude and logic into thought are obliterated.

If this practice is compared with that of tyranny, it seems as if a way had been found to set the desert itself in motion, to let loose a sand storm that could cover all parts of the inhabited earth. The conditions under which we exist today in the field of politics are indeed threatened by these devastating sand storms.

But sand storms are not permanent phenomena. They are destructive but temporary. Their danger, she says, is not that they might establish a permanent world. Totalitarian domination, like tyranny, bears the germs of its own destruction.

The first part of her study deals with the growth of secular antisemitism. The second part deals with the nature, legacy and corrupting nature of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century imperialism. In the third part she shows how the combined and intertwining legacy of these two fatal realities morph into the horror of totalitarianism.

The flawed notions of the rights of man which were championed by Thomas Paine and others flourished over the nineteenth century. Add to that the plague of antisemitism and imperialism which spawned what she describes as “race-thinking.” This in turn undermined the historic model of the nation state and the sense of community which it nourished. The replacement of the old stabilising notion of the nation state generated pan-ethnic consciousness (Germanic, Slav and Russian) which in turn created stateless populations – including Jews – which found no home in those entities. Those entities themselves were partly driven by a desire for conquest and to create new empires. Out of all this emerged classless mobs worshipping a new notion of political power. These became easy fodder to nourish the central and eastern European totalitarian regimes of the twentieth century.

She makes an interesting observation on how the Mediterranean nations somehow partially escaped the frenzy:

“The only countries where to all appearances state idolatry and nation worship were not yet outmoded and where nationalist slogans against the ‘suprastate’ forces were still a serious concern of the people were those Latin-European countries like Italy and, to a lesser degree, Spain and Portugal, which had actually suffered a definite hindrance to their full national development through the power of the church. It was partly due to this authentic element of belated national development and partly to the wisdom of the church, which very sagely recognized that fascism was neither anti-Christian nor totalitarian in principle.”

The real seed-bed of totalitarianism was central and eastern Europe. In the 1920s and 1930s, after the first world war, the chaos among the displaced populations, the ethnic majorities and the corresponding minorities, produced all sorts of conflicts, requiring the setting of new state boundaries. Ireland’s border predicament was a side show in comparison with what mainland Europe was experiencing. But the growth of race-thinking added more poison to the mix. Europe was awash with masses of stateless people. The League of Nations tried to institute what were called “minority treaties” to establish some kind of human rights for these people. They can only be seen as dismal failures.

Add to this confusion the flawed notion of human rights without any philosophical or anthropological foundation – who has them, and on what basis? In principle, the right to have rights, or the right of every individual to belong to humanity, should be guaranteed by humanity itself. But in practice this abstract notion of humanity guaranteed nothing.

The crimes against human rights, which have become a speciality of totalitarian regimes, can always be justified by the pretext that right is equivalent to being good or useful for the whole in distinction to its parts. A conception of law which identifies what is right with the notion of what is good for – the individual, or the family, or the people, or the largest number – becomes inevitable once the absolute and transcendent measurements of religion or the law of nature have lost their authority.

Here, in the problems of factual reality, we are confronted with one of the oldest perplexities of political philosophy, which could remain undetected only so long as a stable Christian theology provided the framework for all political and philosophical problems, but which long ago caused Plato to say: “Not man, but a god, must be the measure of all things.”

She concludes that these facts and reflections offer what seems an ironical, bitter and belated confirmation of the famous arguments with which Edmund Burke opposed the French Revolution’s declaration of the rights of man. They appear to buttress his assertion that human rights were an abstraction, that it was much wiser to rely on an entailed inheritance of rights which one transmits to one’s children like life itself, and to claim one’s rights to be the “rights of an Englishman” rather than the inalienable rights of man (Edmund Burke, Reflections on the Revolution in France). According to Burke, the rights which we enjoy spring from within the nation, so that neither natural law, nor divine command, nor any concept of mankind such as Robespierre’s “human race,” the sovereign of the earth, are needed as a source of law (Robespierre, Speeches, speech of 24 April 1793).

She asserts that the pragmatic soundness of Burke’s concept seems to be beyond doubt in the light of our manifold experiences. Not only did loss of national rights in all instances entail the loss of human rights. The world found nothing sacred in the abstract nakedness of being human. And in view of objective political conditions, it is hard to say how the concepts of man upon which human rights are based – that he is created in the image of God (in the American formula), or that he is the representative of mankind, or that he harbors within himself the sacred demands of natural law (in the French formula) – could have helped to find a solution to the problem.

The survivors of the extermination camps, the inmates of concentration and internment camps, and even the comparatively happy stateless people could see without Burke’s arguments that the abstract nakedness of being nothing but human was their greatest danger.

But Arendt is not a pessimist. Her final judgement echoes – but in a more Judaeo-Christian way – the final frames of Stanley Kubrick’s masterpiece imagining of the future of humanity, “2001: A Space Odyssey”, where the “star child” enters the edge of the screen suggesting a new beginning for mankind.

She reminds us that there remains also the truth that every end in history necessarily contains a new beginning; this beginning is the promise, the only “message” which the end can ever produce. Beginning, before it becomes a historical event, is the supreme capacity of man; politically, it is identical with man’s freedom. Initium ut esset homo creatus est – “that a beginning be made man was created,” said Augustine. This beginning is guaranteed by each new birth; it is indeed every man.

About the Author: Michael Kirke

Michael Kirke is a freelance writer, a regular contributor to Position Papers, and a widely read blogger at Garvan Hill (garvan.wordpress.com). His views can be responded to at mjgkirke@gmail.com.