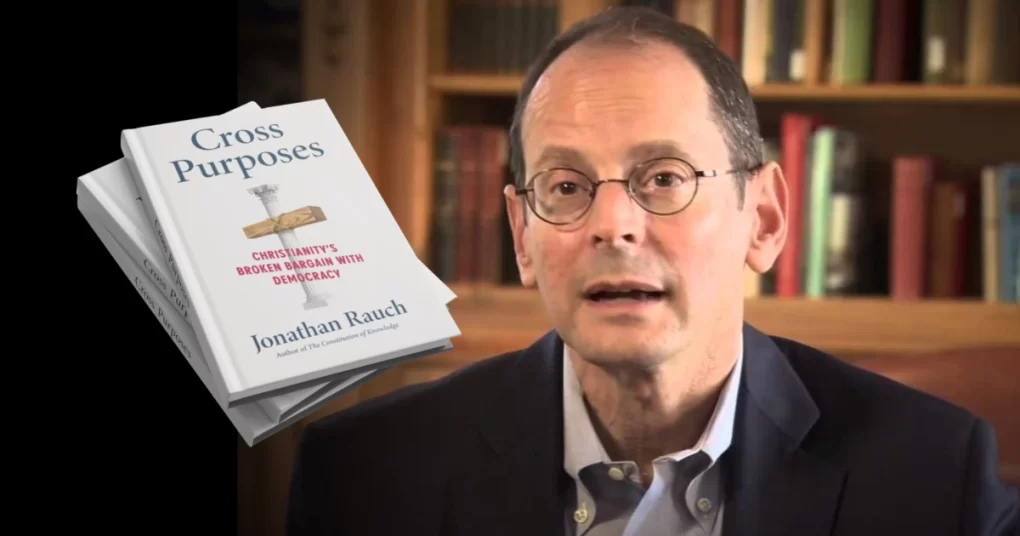

Cross Purposes: Christianity’s Broken Bargain with Democracy

Jonathan Rauch

Yale University Press

February, 2025

168 pages

ISBN: 9780-300273540

In 2003, the prominent journalist Jonathan Rauch wrote an article for The Atlantic which heralded the fact that more Americans were becoming “apatheists”: people who did not care about religion. Religion, Rauch wrote, was “the most divisive and volatile of social forces,” its decline in America and elsewhere was “to be celebrated as nothing less than a major civilisational advance.”

The article was not surprising, given that Rauch, ethnically Jewish, gay, and a convinced atheist from an early age, was one of the most influential campaigners for same-sex marriage in America. The era he was writing in saw the influence of “New Atheism” reach its cultural zenith.

More than two decades on, Rauch begins his new book, Cross Purposes: Christianity’s Broken Bargain with Democracy, with a frank admission: “The 2003 article was ‘The Dumbest Thing I Ever Wrote.’”

Much has changed in those twenty years in America, and by extension across much of the West as well. The United States is by any measure more politically and socially fragmented than it was. Political differences have become political hatreds. After decades of incremental progress after the granting of civil rights, race is now an obsession for much of the left and some on the right. Politics has been coarsened, media coverage has grown shallower and political candidates have become more narcissistic, with the new commander-in-chief being the prime exemplar.

Crucially, America has become significantly less religious.

This short and sharp book does not contain much primary research, but Rauch has clearly done his homework and he cites various works which have detailed the scale of America’s recent secularisation, such as Stephen Bullivant’s Nonverts, Bob Smietana’s Reorganized Religion and The Great Dechurching by Jim Davis and Michael Graham.

A few of the statistics which are included demonstrate the significance of this shift. Almost half of Americans self-identified as practicing Christians in 2000, but this has fallen to a quarter. Overall, there are about forty million American adults who used to go to church but now do not. Whereas 62% of Americans said that religion was “very important” to them in 1998, only 39% said the same in 2023.

America is a troubled society, and America is a secularising society.

Both of these statements would likely be recognised as true by the vast majority of observers, but Rauch breaks from many of his fellow secular liberals in his belief that these two developments are closely interlinked, and this book can be interpreted as an alarm bell sounded for the benefit of Rauch’s fellow non-believers.

“I came to realise that in American civic life, Christianity is a load-bearing wall. When it buckles, all the institutions around it come under stress, and some of them buckle, too,” he writes.

Examining the increasing social problems such as “deaths of despair,” Rauch refers to the social science evidence on the benefits of religious practice while writing that the communal functions of religion are proving hard to replace.

His core thesis is much broader and deeper in its scope. It is not so much a case that Christianity is vital for the overall health of many Americans, but that Christianity is vital to the health of the American democratic project itself.

According to Rauch, recent experiences of state failure overseas have demonstrated the difficulties involved in trying to embed democracy in nations which lack a supportive cultural underpinning.

With admirable self-reflection, he acknowledges that he previously “did not appreciate the implicit bargain between American democracy and American Christianity,” further adding that he “should have paid more attention to the American Founders who, while opposing the admixture of religion with government, warned that republicanism would rely in part on religious underpinnings.”

Casting his eye across American Protestantism, Rauch sees how some of the more liberal churches have haemorrhaged membership while increasingly coming to adopt the values of the wider culture. He is much more critical of those Evangelical churches which have come to embrace Trumpism and a more confrontational and destructive form of politics.

In both these cases, the churches – be they liberal or conservative – are conforming to the world rather than seeking to transform it. Rauch perceptively identifies the degree to which this is a problem for non-believers living in a nominally Christian society. “[W]e secular atheists rely on Christianity to maintain a positive cultural balance of trade: we need it to export more moral values and spiritual authority to the surrounding culture than it imports. If, instead, the church is in cultural deficit – if it becomes a net importer of values from the secular world – then it becomes morally derivative instead of morally formative.”

As well as being a keen observer of American social trends, Rauch possesses a deep understanding of the philosophical origins of Western liberalism. He takes issue with the post-liberals on the American right by stating that various liberal theorists have long warned that “liberalism requires outside sources of support and stability,” given that the liberal system itself lacks a clear unifying vision of the right way to live.

Here he may well be right. Yet in his growing support for a religious contribution to civic life, he is surely (and regrettably) a minority among self-professed liberals or “progressives,” who often go to great lengths to drive religious people out of public life and public institutions: at least when their religious beliefs appear to influence their actions in any significant way.

Rauch’s assessment of the limitations of mainline Protestant churches in America is particularly interesting, given that their liberal views on social issues broadly conform with his own.

The second term of the Trump presidency began with a spectacular intervention by the Episcopal Bishop of Washington, Mariann Budde, who used her pulpit in the National Cathedral to denounce the President’s attitude to “gay, lesbian and transgender children” – a coded reference to Trump’s sensible opposition to gender transition treatments for those below eighteen.

Bishop Budde’s theatrically Woke sermons are not likely to bring about any revival in the fortunes of a religious institution which now has only around 1.5 million members.

Unlike other liberals, Rauch does not pretend that a more progressive approach will lead to the pews being filled once again. Instead, he explains that “the mainline church cast its lot with centre-left progressivism and let itself drift, or at least seem to drift, from scriptural moorings.”

Put more bluntly, there are many places in which someone in Washington could hear what Mariann Budde has to say about the world – why, then, should they venture into her church?

His criticism of Trump-supporting Evangelicals is much more vociferous, and to some extent justified.

Rauch quotes findings from the Public Religion Research Institute from 2011 which showed that only 30% of white Evangelicals believed that “an elected official who commits an immoral act in their personal life can still behave ethically and fulfil their duties in their public and professional life.” When Trump was running for president in 2016, that figure had very conveniently risen to 72%; once again, Christians were conforming to the world rather than seeking to transform it.

The author devotes a large section of the book to the manner in which the Mormon church has entered into various accommodations relating to gay rights without changing their own teaching on homosexuality or the definition of marriage.

This is interesting, but Rauch strangely bemoans the fact that the word “compromise” is not mentioned a sufficient number of times in a recent document on “Forming Consciences for Faithful Citizenship” issued by the Catholic bishops.

While the book is overwhelmingly about the Protestant Christianity which has shaped America, the failure to examine the Catholic Church’s record is a considerable deficiency in this work. American Catholicism contributes vastly more than the Mormons do to America’s civic life – not to mention in education, healthcare and social services sector.

Compromise in Church-State matters is a constant for Catholic bishops worldwide, and the American Church has been the victim of numerous instances where secular liberals have behaved egregiously: most notably when it comes to the secularist opposition which has prevented Catholic schools from receiving any significant level of public support (in spite of Catholic parents being taxpayers themselves).

That being said, Rauch does conclude by emphasising the need for American secularists like himself to be more open to religion generally.

“[E]fforts by secular groups and activists to police the landscape for religious incursions into the public sector seem to be equally misguided and counterproductive,” he admits, while adding that he supports the recent trend by the (much maligned, and majority Catholic) US Supreme Court in taking an expansive view of religious freedom.

He even goes as far as to label ongoing efforts to coerce Christian bakers into producing gay wedding cakes as “doctrinaire totalism.”

Jonathan Rauch has not abandoned his atheism or his commitment to a state separated from religious authority, but the discussion which he seeks to open with religious Americans is a reasonable one.

The book is dedicated in loving memory to Rauch’s Christian friend, who faced his awful death from ALS with a fearlessness which made Rauch embarrassed about his own “spiritual poverty.” Indeed, he writes that the book has been written in penitence for the 2003 article in The Atlantic and his earlier closed-mindedness.

“Too often, secular Americans have acted as if allergic to religious teaching. We should never, ever, pass a law because someone thinks Jesus said to; yet our laws might be better if we more often asked what Jesus might have said about them,” he writes.

This book deserves to be widely read by Christians and secularists alike. It should be a starting point for a broader conversation all across the post-Christian West, where the fading of Christianity has left prosperous and educated societies with a void which they have not filled and never will.

About the Author: James Bradshaw

James Bradshaw writes on topics including history, culture, film and literature.