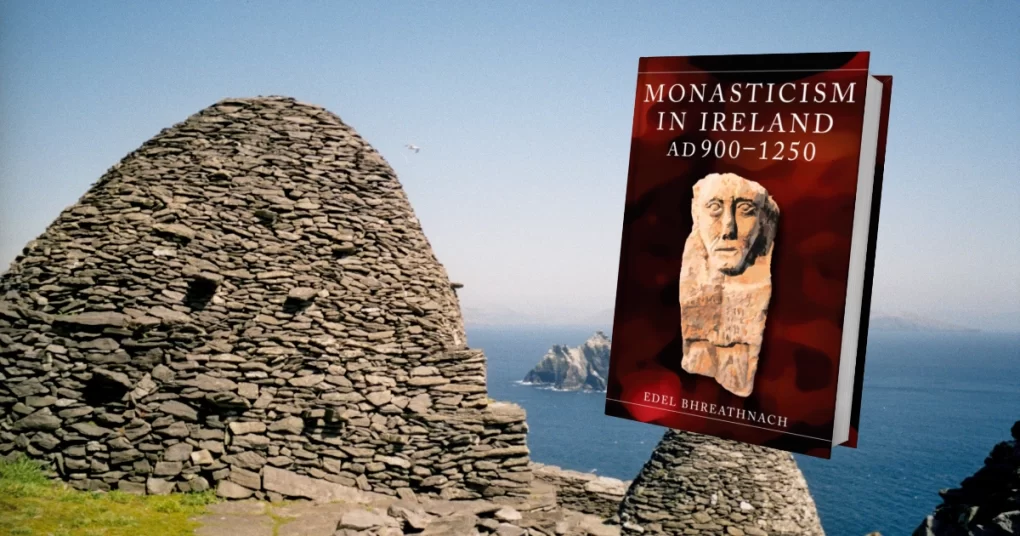

Monasticism in Ireland, AD 900-1250

Edel Bhreathnach

Four Courts Press

September 2024

540 pages

ISBN: 978-1801511179

Monasticism in Ireland, AD 900-1250 is the new prize-winning book by the medieval historian Edel Bhreathnach. The author previously served as the CEO for the Discovery Programme, the national archaeological research body. She has clearly brought a massive body of knowledge to bear while producing this engaging examination of an important aspect of the Irish Church’s history.

It is an indication of Bhreathnach’s thoroughness that more than a hundred pages are dedicated to the primary and secondary sources on the history of Irish monasteries, and the various (and often contending) schools of thought about them. It is certainly a complicated subject and one where a large amount of confusion exists. As the author states early on, it is an ingrained habit in Ireland to refer to medieval church ruins as “monasteries,” when many were nothing of the sort.

In the confused ecclesiastical structure of Gaelic Ireland, there were many hermitages present along with very small religious communities which were not truly monastic. Many Irish towns are thought of as being monastic in origin, but Bhreathnach writes that other scholars have often contended that Ireland was “uninfluenced by Roman urbanisation and [that] genuine nucleated settlements only appeared in Ireland with the growth of the Norse coastal towns.” She takes issue with this, affirming that monastic settlements like Armagh, Clonmacnoise, and Glendalough were indeed significant, being similar to the monasteries of continental Europe. In these towns, Irish monks “provided leadership, and material and spiritual guidance in return for economic supplies and the products of other skills, both artisan and intellectual.”

The existence of such communities creates a further difficulty when seeking to understand them. The word “manach” is generally taken to mean “monk,” and yet the author quotes an earlier academic suggesting that in early Irish texts at least, a “manach” could also be a tenant living on monastic land. With so many churches being mistaken for monasteries and so many laymen being mistaken for monks, it is easy to see why some have overemphasised the degree to which the Irish Church was monastic rather than diocesan in its structure. As Bhreathnach describes it, this was a mixed system: “Pastoral care functioned under the jurisdiction of bishops and a secular clergy, although diocesan and parish formation was organised to take account of a kin-based society and the interests of large corporate structures.”

If not anarchic in its political structure, Gaelic Ireland was at the very least complicated, with its clans, túatha, and many kings. As pastoral farming was a crucial part of the people’s lives and livelihoods, large-scale movement of people and livestock was a constant source of instability. In this environment, it is no surprise that the Church was less well structured than it was on the continent, and what order did exist in Ireland came in large part from the efforts of the clergy.

“Like many modern monasteries, which run schools, third-level institutions, farms, health-care, and social-care institutions with the assistance of government and community support, early Irish monasteries operated on a similar basis,” she writes. “Not only did they own large estates, but the larger monasteries also had guesthouses, hospices, and libraries and were centres of ecclesiastical and vernacular learning. Most large and middle-sized foundations housed coenobitic communities who followed an ascetic lifestyle based on universal monastic precepts, and on occasion either individuals or groups of monks lived more eremitical lives in specially designated hermitages, some close to their monasteries, others quite a distance away.”

The solitudinous nature of some Irish monasteries is shown by how many Irish place names include “díseart,” often followed by a personal name. Some of the best examples of monastic settlements in isolated environments are those on islands off the southern and western coasts. Skellig Michael and other monastic ruins certainly make the harsh realities of monastic life clear. In comparing the Irish monastic experience with that which existed in other parts of Europe, Bhreathnach suggests that the Irish monks favoured a comparatively “more severe asceticism,” more akin to the original eastern and north African traditions.

Following the Reformation, Protestant revisionists writing in the service of their British masters frequently sought to downplay the historical connection between the early Irish Church and Rome. Historical examinations of the monastic tradition in Ireland have been coloured by such charges, and by the attempts of zealous Catholic historians to right the historical record. On this issue, Bhreathnach appears to lean towards the Catholic counter-argument, noting that scholars have emphasised “the complex nature of Christian liturgy and the plurality of Christian experience, similar to diverse monastic traditions, of which Irish practices were but one of a myriad.”

The author’s account ends at the beginning of the thirteenth century, by which time the Normans were expanding their influence on both the Irish Church and Irish society. This cut-off point is also shortly before the arrival of the mendicant orders – particularly the Dominicans and the Franciscans – who would play such a crucial role in the subsequent history of Irish Catholicism, not least in the successful battle to preserve the Faith against foreign persecution. Bhreathnach’s book is a scholarly work rather than one aimed at the general reader. That being said, it offers valuable insights into the aforementioned historical disputes and complexities.

The monastic tradition has been important throughout Ireland’s history, and it was well-suited to the social realities of life in Gaelic Ireland: arguably more so than the diocesan structure which eventually succeeded it. More importantly, the monastic structure is one which Irish Catholics may have to turn to again in the coming decades. The parish model can only truly work if two conditions are in place: the presence of an adequate number of practising Catholics in each parish, and the availability of at least one priest to serve each parish. Soon, neither of these conditions will be in place, and a system consisting of more than 1,300 parishes in Ireland will be in danger of collapse.

Conversely, some thriving religious communities are being established in various places across this secular landscape. Some of these are fully monastic (witness the success of the Dominicans) whereas some are only quasi-monastic, if at all so. Few are full monks; most are visiting pilgrims who come to pray, to learn, to break bread, and then go back out into the world. In a more interconnected modern age, people are able to travel more freely, while also benefiting from other forms of virtual contact. The loss of parish churches in the coming years will be traumatic on many levels, but it need not be a major blow in terms of functionality.

Rather than looking at this as a battle to sustain thousands of churches, we need to consider how best to ensure that a much smaller number of religious communities can serve as focal points for a re-evangelisation. The witness these communities give will be much more important than the presence of empty buildings. What will exist in the future will not be the same as what served us in the past. But learning from our past is vital before considering the best course to take.

About the Author: James Bradshaw

James Bradshaw writes on topics including history, culture, film and literature.