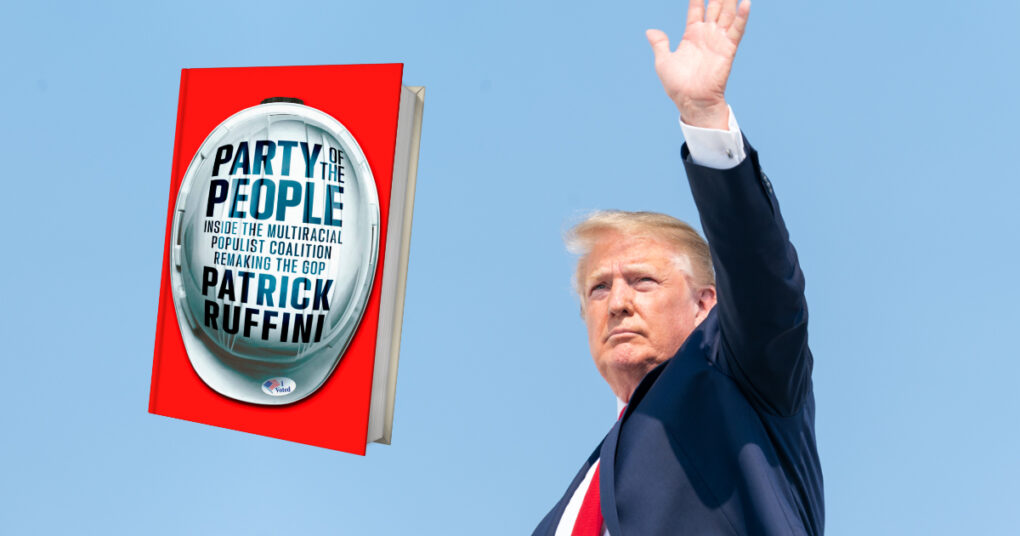

Party of the People: Inside the Multiracial Populist Coalition Remaking the GOP

Patrick Ruffini

Simon & Schuster

Nov. 2023

336 pages

ISBN: 978-1982198626

Donald Trump’s stunning victory has not yet resulted in a renewed and thorough examination of political trends in America. Some have commented on the growing support which Trump’s Republicans are receiving from minority voters. The results were truly remarkable. Trump apparently carried 46% of Hispanic votes along with 39% of Asian votes, and serious inroads were also made with younger African-American males. Considering that Trump had already significantly increased his support among minorities in 2020, an important trend has now emerged.

In 2023, a book titled Party of the People: Inside the Multiracial Populist Coalition Remaking the GOP was released. Though the author Patrick Ruffini’s credentials as a Republican pollster and commentator were never in doubt, the Republican Party’s relatively poor performance in the 2022 midterms likely meant that not enough attention was dedicated to this book at the time.

Ruffini freely admits that he is nobody’s idea of a standard Trump populist. His educational and professional background shows him to be the embodiment of what is meant by “Establishment Republican.” Yet unlike many, Ruffini did not let his initial dislike of Donald Trump prevent him from trying to understand his political appeal.

He was shaken by his experience and that of many of his fellow Washington DC Republicans who did not foresee that Trump would attract so many non-college educated voters to their party in 2016. Not only did their life experiences not allow them to see what was happening, it actually prevented them from seeing it. “[M]yself and those in my peer group were unable to see objectively what was happening because the trend was happening to us. Virtually no one in our group possessed the demographic characteristics that would let them see the appeal of Trump’s blunt-talking style,” he admits.

Years later, Ruffini embarked on a detailed study of what has been happening, and his book is an effortless blend of psephology, modern political history and sociological analysis (drawing upon essential works by Charles Murray, Tim Carney and others).

Dispensing with the antiquated concept of “working-class” which revolves around industrial employment, Ruffini posits that the fundamental socio-economic divide in today’s America is between those who possess a college degree and those who do not – including the tens of millions of Americans who have some college education, but who never graduated.

He divides the American electorate into three broad groupings: whites with a college degree, whites without a college degree and non-whites. Examining the evidence of recent elections and looking at the raw numbers in terms of educational status, Ruffini shows that although college-educated whites have moved to the left politically, the other two groupings have moved significantly to the right, to the great benefit of Trump and his Republican Party.

This new coalition, he writes, includes a “supermajority of workers across white-collar, blue-collar, and service industries who hold positions where a college diploma is not a requirement, didn’t work from home during the pandemic, and aren’t agitating for their employer to take a stand politically.”

Ruffini’s findings suggest that college-educated professionals are further to the left than those without a college degree. Non-graduates tend to be more conservative socially, and liberalism is only strong as an ideology among that category of “college whites” – oddly, there is not the same cultural and political divide between Hispanics with college degrees and those without them, or between black Americans with college degrees and those without them. This political polarisation between American college graduates and non-graduates only began to appear in the social science data from the late 1990s onwards.

College graduates tend to concentrate in large cities where the prevailing culture is socially progressive. Americans of higher socio-economic and educational status tend to live in similar areas and tend to marry people of a similar background – all of which has helped to create a country which is more politically and economically segregated.

One consequence of this can be seen in today’s Democratic Party. At the time of writing, Democrats in the US Congress represented 65% of taxpayers making $500,000 or more. They are the party of the rich now. Ruffini describes driving through the leafy Washington DC suburbs during the 2020 election and seeing a yard sign reading: “In this house we believe / Black lives matter / Women’s rights are human rights / No human is illegal / Science is real / Love is love / Kindness is everything.” He points out that not one of these slogans related to economic disadvantage. The sign belonged to a lifestyle liberal of the Kamala Harris variety, of which there are now tens of millions.

Whereas the Democratic Party used to be a coalition of various groups (including union workers, African-Americans, white ethnic groups like the Irish and so forth) in which left-wing beliefs were common but not predominant, this has now changed. What now exists in America is a broad segment of voters who hold moderately conservative views on cultural issues (without being outright social conservatives) while also being supportive of economically interventionist measures. In the 1980s, many such voters could have been classified as “Reagan Democrats.” In subsequent decades, they veered between the parties, often being won over by skilful Democratic candidates like Bill Clinton and Barack Obama who knew how to appeal to the white working-class. Gradually, whites without college degrees became a core component of the Republican coalition. What has truly revolutionised American politics is the more recent shift in which non-white groups have followed them in abandoning the Democrats.

Ruffini shows that there are many historical parallels where previously loyal Democrats shifted allegiances. For example, when Kennedy was elected in 1960, he carried more than 70% of white Catholic votes, but Republicans had almost half the white Catholic vote by the Reagan era and now hold a commanding lead in this demographic.

Hispanic Americans are now travelling the same road as the Irish and Italians did. This process is multi-faceted, as there is no standard or uniform Hispanic/Latino community. Some Cuban, Colombians and Venezuelan Americans have been appalled by the rise of socialism within the Democratic Party, and have voted Republican as a result, turning a former purple state like Florida deep red. Puerto Ricans and Mexican-Americans living in the Rio Grande Valley in Texas lack a shared experience of seeing their ancestral homelands ruined by leftism, and yet they too have moved towards the Republicans. Overwhelmingly Hispanic counties in Texas which voted Democratic until recently have now gone over to the Republicans.

Why is this? As average Hispanic income levels rise, sympathy for the Republicans increases. Many are deeply turned off by Woke culture or the use of ‘Latinx’ (an ungrammatical but gender-neutral term for Latinos which has been promoted relentlessly by white progressives). Some also find Trump’s blunt speaking style and machismo attractive; Ruffini makes the point that Trump’s strongman persona and his approach of positioning himself as a businessman seeking to clean up politics, closely mirrors how political campaigns often work in Latin America.

Social issues like abortion, on the other hand, seem not to be a major factor in Hispanics moving rightwards. The new Republican coalition is conservative in its opposition to a progressive ideology focused on perceived power structures and inequities, but in the more unchurched America of today, this new type of conservatism is not especially religious. Many Asian-Americans (often from non-Christian backgrounds) have also moved into the Republican camp due to Democratic assaults on merit-based admissions in education.

Whatever the reason for these shifts, they are not slowing down. Voters from minority backgrounds are becoming more likely to vote Republican the longer they live in America, with younger minority voters abandoning their parents’ filial loyalty to the Democratic Party.

The exception to this rule is the African-American community, where the movement to the Republicans is much less noticeable, and generally involves younger men only. Ruffini points out that African-Americans still have not seen the same intergenerational progress in incomes as their Hispanic or Asian neighbours, while also pointing to research showing that the enduring strength of black social spaces (such as the African-American churches) is part of what has kept blacks within the Democratic fold.

In one of the strangest situations in modern America, it now appears that a decline in church attendance by blacks could aid the Republicans; while 48% of black Christians consider themselves to be “strong Democrats,” only 31% of secular blacks do. This demonstrates the complexity of American society, where social atomisation generally benefits the left but can occasionally be a boon to the populist right.

Regardless of what happens when it comes to immigration policy, America is on its way to becoming a majority-minority country where whites are less than 50% of the population. Will this doom the Republican Party? Certainly not given the evidence about voting patterns, and given the fact that the Republican Party still remains extremely dominant in Texas, which is already majority-minority.

Ruffini’s overall case is highly compelling. What it means for American politics is that, for the moment, the Republicans are in a far better position. The college graduation rate has not increased significantly over the last forty years and there are simply more votes available to the Republicans. With the structure of the Electoral College and the Senate favouring the GOP, it will be a long road back for the Democrats even if they manage to tame their overzealous Woke activist wing and start broadening their tent again.

It is worth pondering what it is about a modern university education which makes graduates so much more left-wing than the population writ large, what it is that narrows the mind rather than broadening it. Ruffini does not dwell on this question. What he does is make a persuasive case for policymakers – particularly those of a conservative viewpoint – to focus on the desperate need for more non-college options when it comes to giving people the tools they need to prosper in the modern economy.

His policy prescriptions are commendable: more apprenticeships; the elimination of unnecessary degree requirements and the need for more recruitment efforts aimed at people from working-class backgrounds; among other proposals. Steps such as these, he writes, would boost social mobility, thus “reversing the economic calcification and social division that came about as a result of the college sorting machine in postwar America.”

Much of this can be applied to address similar problems which exist in other countries also, where a similar divide has grown up between the working-class in forgotten communities (usually native-born, and sometimes wary of large-scale immigration) and the new socio-economic elite concentrated in the larger cities and more affluent areas.

“Party of the People” is uniquely valuable as an explainer for how Donald Trump built a coalition to allow him to return to the White House, but it has a vastly wider relevance. It should be looked upon as one of the true “must-read” politics books of recent years.

About the Author: James Bradshaw

James Bradshaw writes on topics including history, culture, film and literature.