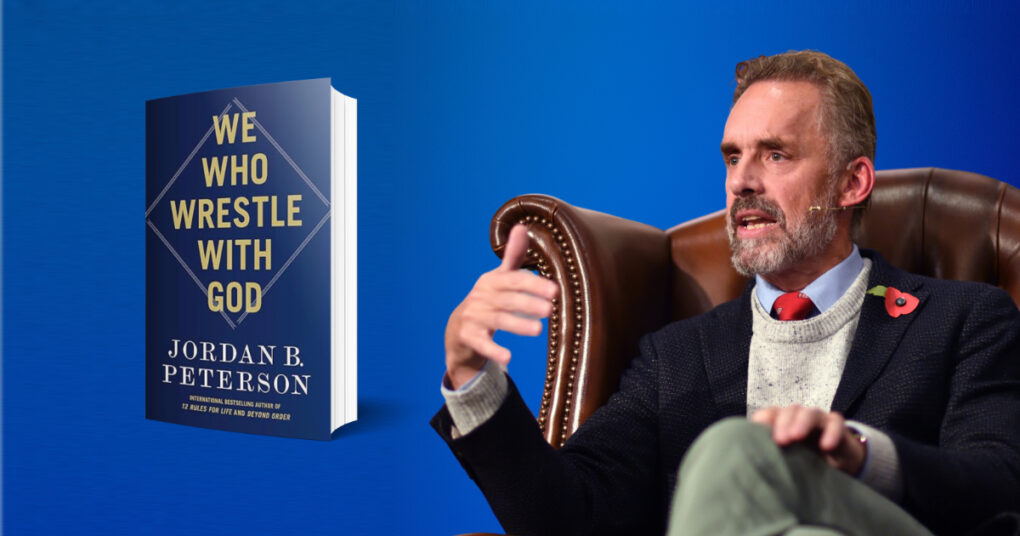

We Who Wrestle with God

Jordan B. Peterson

Allen Lane

Nov. 2024

576 pages

ISBN: 978-0241619612

We Who Wrestle with God is Jordan Peterson’s fourth book, succeeding the lesser known Maps of Meaning: The Architecture of Belief, (1999), and his two very successful works: 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos (2018) and Beyond Order: 12 More Rules for Life (2021). The genesis of the present work seems to be the 2017 series The Psychological Significance of the Biblical Stories which was delivered both live and as podcasts. The objective in this series was much the same as this book: to analyse archetypal narratives in the Book of Genesis as patterns of behaviour vital for personal, social and cultural stability. The present work is to be followed by a similar work based primarily on the New Testament.

The book however has not been well received. It has been panned by some critics, for example James Marriot in The Times (“Repetitive, rambling, hectoring and mad) and Helen Coffey in The Independent (“I gamely try to drag my brain kicking and screaming through the tangled mixture of waffle and bluster, needlessly archaic language and sweeping, unequivocal statements posing as absolute truths”), while receiving gentler but actually more pointed criticisms such as those of John Gray in the New Statesman (“Peterson’s self-made God is a symptom of the modern Western malady, rather than a cure for it.”) and Rowan Williams in the Guardian (“This is an odd book, whose effect is to make the resonant stories it discusses curiously abstract.”)

Over the course of the 500 pages of We Who Wrestle with God, Jordan Peterson looks at the Bible stories of Adam and Eve, Cain and Abel, Noah, Abraham, Moses and Jonah, and draws out the meaning or the moral of each story, the moral generally being that without moral rectitude one is doomed. These Bible stories are generally paralleled with ancient mythology, in particular the Babylonian Enuma Elish creation myth. The morals which Jordan Peterson draws from these stories are ones which Jordan Peterson has courageously defended, even at the cost of his own health, in the face of huge opposition: the damaging nature of porn and sexual licence, the good of monogamy, the need for society to be founded on some sacred principles, and that boys are boys and girls are girls.

Nevertheless, as one works ones way through the book it becomes clear that while the values he defends are quite Christian, his underlying worldview is certainly not.

Firstly he is a radical pragmatist. His fundamental guiding principle that “what is most deeply necessary to our survival is the very essence of ‘true’.” He recognises, for example, the uniqueness of the Bible, not on account of an intrinsic sacrality, but because it has produced the West.

Secondly he firmly adheres to the bizarre doctrine of the collective unconscious of Carl Jung, whereby the human mind is biologically hard-wired with a series of fundamental archetypes or primal symbols which act as “deep cultural coding” or “maps of meaning” (to use Jordan Peterson’s own phrases), presumably to assist with one’s survival and flourishing. These archetypes manifest themselves in all kinds of human artefacts: mythologies, literature and cinema … and the Bible.

Jordan Peterson is in essence subjecting these iconic Bible stories to a Jungian reading. Virtually all the characters, actions and things which appear here become “mythological tropes” which can be interpreted with breath-taking ease. We are told that the six days of creations “means” that life “will constantly move from good to very good”; that “created in the image of God” “means” the human spirit is “the mediator of becoming and being”; and so on. There is virtually nothing which is immediately transparent to his powers of Jungian interpretation: why the ground is cursed, why Adam and Eve clothe themselves, why they are expelled from paradise, why the cherubim have flaming swords, why Abel kept sheep, who are the mysterious Nephilim of Genesis 6:4, what the rainbow represents (“it represents the ideally subdued community” in case you were wondering); what is the significance of Lot’s backward glance, of David fighting Goliath, of the burning bush, of the staff of Moses…. The Jungian gaze can also penetrate the meaning of extra-biblical human productions: the Pietà, Harry Potter, Superman, Cinderella’s glass slippers, Obi-wan Kenobi’s light saber and so on, and so on.

And so one is left with the impression that the original text will mean “whatever he wants it to mean” as one critic has put it. Jordan Peterson gives scant importance to the literal meaning of the texts he examines. In approaching the Bible in this way he violates the first classic rule of scriptural exegesis: that the literal meaning of the text is foundational and primary. Subsequent “spiritual” meanings, such as morals to be drawn, or allegories to be identified must be firmly founded on the literal meaning. And this is where the hard work of exegesis begins. This requires a knowledge of things like the original language of the text, historical context, parallel texts, the genre being used, etc. None of this is to be found in We Who Wrestle with God.

In his zeal to uncover Jungian archetypes, Jordan Peterson pays little attention to the scholarly task of unearthing the literal meaning of the texts in question. No bibliography is provided but a cursory look at the table of notes at the end of the book is quite revealing. Of the almost 600 reference notes at the end of the book, only are handful are to works of scriptural exegesis, and virtually none of these would appear in a work of serious scriptural investigation. Most of the commentaries he references date from the nineteenth century and happen to be available on biblehub.com. Where it comes to matters psychological on the other hand, the references are abundant and scholarly, being taken from academic works and journals. This just reinforces the impression that the scriptural texts and stories serve as mere cyphers – nothing in themselves but deriving their importance as a code for some stoic moral tale or cultural symbol.

But what is more serious, his rush to allegorise the texts means that he misses some of the fundamental lessons they convey. Perhaps the most egregious case is in his interpretation of the Genesis account of the creation of the world, which he repeatedly treats as equivalent to other ancient creation myths, such as that in Babylonian Enuma Elish, or from Chinese Taoism, leading him to render the Hebrew term for “the deep” or “the waters” (tohu wa bohu) in Genesis 1:1 as “The Dragon of Chaos”, when, according to the Jewish scripture scholar Umberto Cassuto, it simply means the “chaos of unformed matter”.

For Jordan Peterson all these creation accounts tell the same story: creation involves a never-ending battle between a spirit of order and a sinister spirit of chaos, between good and evil. While the good spirit generally has the upper hand, the spirit of chaos is always lurking at the root of things, waiting to attack. The problem with this is that the Genesis account says no such thing, in fact far from echoing other creation myths Genesis is attacking them! It presents a vision of creation profoundly at odds with all other creation myths. In the words of the great Umberto Cassuto:

Then came the Torah and soared aloft, as on eagles’ wings, above all these notions. Not many gods but One God; not theogony, for a god has no family tree; not wars nor strife nor the clash of wills, but only One Will, which rules over everything, without the slightest let or hindrance; not a deity associated with nature and identified with it wholly or in part, but a God who stands absolutely above nature, and outside of it (Umberto Cassuto, A Commentary on the Book of Genesis: from Adam to Noah).

How wrong Jordan Peterson is to draw an equivalence between these competing accounts of creation. In Genesis there is anything but “… the eternal dynamic of order and chaos …”. But this is not a merely technical error. Ideas have consequences, and ideas about the constitution of all of creation have very far reaching consequences. Jordan Peterson’s conception of creation is closer to the Manichean than the Judeo-Christian. Throughout the entire book looms the spectre of “hell” (it receives 117 mentions in the book), “the abyss”, “existential catastrophe”, “an endless wasteland”; creation and life is a burden that we have to “hoist … on our shoulders”; our relationship with God who “calls us out into the terrible world” is – as the book’s title suggests – a titanic struggle.

One finishes the book drained. God here is the depersonalised “eternal spirit of Being and Becoming”, “the unity that exists at the foundation or stands at the pinnacle” and is real “insofar as its pursuit makes pain bearable”. It is pragmatic to follow the dictates of this “God” (“the best strategy of defence”) but utterly absent is the sense that God might love us, and that we might even be able to requite this love. Anything that might suggest such a relationship is always sanitised through the use of scare quotes; there can be no belief, faith and religion but only “belief”, “faith”, and “religion”. Sadly, for a book whose subtitle is “Perceptions of the Divine” one is struck by the sheer absence of God.

About the Author: Rev. Gavan Jennings

Rev. Gavan Jennings is a priest of the Opus Dei Prelature. He studied philosophy at University College Dublin, Ireland and the Pontifical University of the Holy Cross, Rome and is currently the editor of Position Papers.