The final years of the nineteen hundreds and the early years of the succeeding century produced two thinkers whose ideas had an enormous influence on our culture over the twentieth century, extending even into the present age.

Both were effectively enemies of religion, even virulently so. One will be familiar to us, his name even having a byword status in our language. The other is not so familiar but, regardless of that, they both left a mark on our culture which did much to transform it from an essentially Christian one into a post Christian atheistic one.

The first of these is Sigmund Freud. The second is the anthropologist, Sir James Frazer. Freud’s legacy is a vastly more extensive one than that of Frazer – and not malign in all its aspects. But his reading of man’s nature and his emphasis on sexual appetite as the root of our desires has been both a determinant of the under-belly of our popular culture and a potent force destroying many of the noble values which have characterised our civilisation for millennia.

Sir James Frazer’s seminal work is The Golden Bough, famous enough and influential enough to be very meaningfully referenced in Francis Ford Coppola’s film, Apocalypse Now. Frazer is not taken very seriously by professional anthropologists but that does not diminish his influence on our culture. Frazer’s destructive idea helped sow the seeds of twentieth century agnosticism and atheism.

Frazer presented The Golden Bough as an exhaustive study of human mythology and how it reveals to us the deeper aspects of anthropology. In particular he focused on the pervasive phenomenon of scapegoating as the cathartic agent which rescued human societies from one catastrophe after another. Think of the myth of Oedipus here. Frazer’s grave and destructive error, however, was to include the scapegoating, suffering and death of Jesus as just one more myth in the long catalogue which he assembled. He failed to see the radical difference between the scapegoating of Christ and all the others in his list – remember, Caiphas did present Christ to the Sanhedrin as such.

“Nor do you understand that it is expedient and politically advantageous for you that one man die for the people, and that the whole nation not perish” (John 11:50).

But neither Caiphas nor Frazer understood the true meaning of Christ’s voluntary sacrifice for the redemption of mankind.

There is one twentieth century thinker who many regard as one who by the end of this century will be regarded as one of the greatest influences on our time and whose thought will explode the fallacies perpetrated by, among others, both Frazer and Freud. His reading of man as man and our relationship with God and the world will tower head and shoulders over all others. He will do so because he directly confronts Freud’s corrupt reading of the roots of human desire. He also demolishes Frazer’s simplistic confusion of the phenomenon of mythological scapegoating with Christ’s truly salvific sacrifice on the Cross.

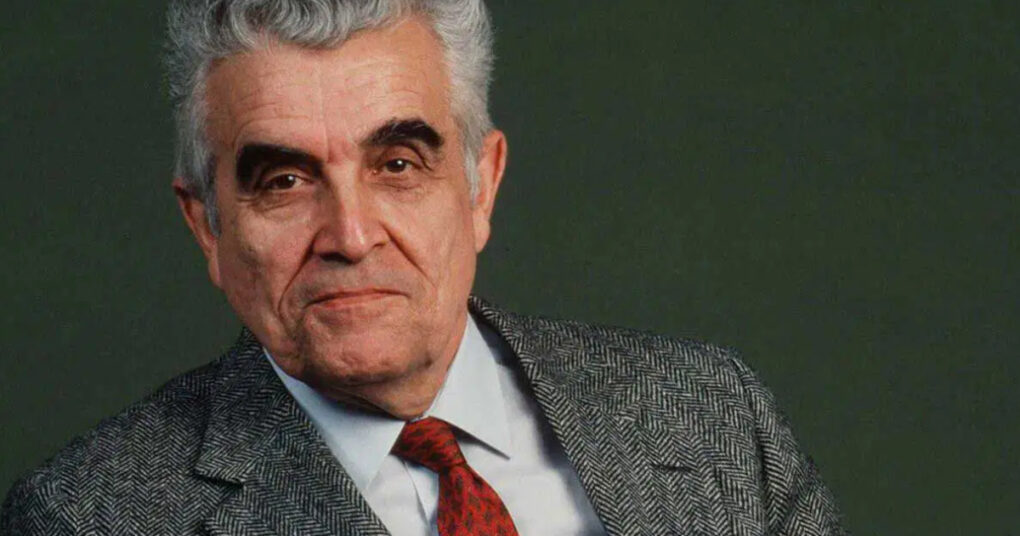

This man was René Girard (1923-2014). Girard was a man whom Bishop Robert Barron describes as one of the great Catholic philosophers of our time and predicts that in the future his influence will be regarded as that of a modern Church Father. Girard was a member of the Académie Française, taught in the universities of Indiana, Johns Hopkins and finally in Stanford. Barron classifies two types of academics, those who beguile you with brilliant ideas and those who will shake our world. Girard, he says, was one of the latter. The Canadian sociologist, Charles Taylor, writes of the “ground-breaking work” of Girard. In reading contemporary attempts of our efforts to confront our society’s problems it is not unusual to find writers talk of ‘Girardian’ approaches to these.

But his influence is multifaceted and penetrates into the secular world in a remarkable way. He has influenced some of the leading movers and shakers in Silicon Valley – people like Peter Theil and Mark Andriessen. J.D. Vance has attributed his conversion to Catholicism to reading Girard. Thiel, founder of PayPal and now one of the West’s leading public intellectuals studied under Girard at Stanford. He has said that Girard has had a tremendous impact on his life, and considers the author’s book Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World to be Girard’s masterpiece.

Theil says “Girard ranges over everything: every book, every myth, every culture — and he always argues boldly. That made him stand out against the rest of academia, which was and still is divided between two approaches: specialized research on trivial questions and grandiose but nihilistic claims that knowledge is impossible. Girard is the opposite of both: He makes sweeping arguments about big questions based on a view of the whole world. So even when you set aside the scandalous fact that Girard takes Christianity seriously, there is already something heroic and subversive about his work.”

Bari Weis, former Wall Street Journal and New York Times writer, and now upsetting mainstream media’s applecart as founder-editor of The Free Press, published a series recently listing nine twentieth century prophets. Girard was one of them. The piece on Girard was by one of his recent biographers, Cynthia Haven.

Haven reflected on how “Today, a single tweet could wreck a career. It could even bring down a government, if the stars are aligned. Mobs gather online instantly, ideologies form seemingly overnight, and cancel culture punishes those who dare dissent. This precarious, pernicious world is the one we live in now. But decades before anyone had heard of “doxxing” or “downvoting” or “dragging,” a French literary scholar at Stanford, born more than 100 years ago, warned of what was to come. He foresaw the perils of combining human nature with a globally connected world.”

“When the whole world is globalized, you’re going to be able to set fire to the whole thing with a single match,” predicted Girard.

In Girard’s deep and penetrating study of the nature of human desire – forget Freud’s blinkered sexual preoccupations – he explored envy, imitation, crowd behaviour, and reciprocal violence. Starting in the 1950s, he first developed his insights not by poring through datasets or running a social science lab but, surprisingly, from a deep study of great literature. Great novels tell us the truth, he said. In them we see the truest reflections of men and women’s inner being.

Girard was not a superficial optimist. Neither was he a grim pessimist. He was a man of Faith and Hope but he did take the apocalyptic passages of Sacred Scripture seriously. He looked at the point at which we have now arrived in human history and worried deeply about what he saw unfolding. He takes very seriously the apocalyptic passages in the New Testament. For example the second letter of St Peter:

“Since all these things are thus to be dissolved, what sort of persons ought you to be in lives of holiness and godliness, waiting for and hastening the coming of the day of God, because of which the heavens will be kindled and dissolved, and the elements will melt with fire! But according to his promise we wait for new heavens and a new earth in which righteousness dwells.

“Therefore, beloved, since you wait for these, be zealous to be found by him without spot or blemish, and at peace. And count the forbearance of our Lord as salvation. ”

Girard has written, “History you might say is a test for mankind but we know very well that mankind is failing that test.” (quote from his book, Battling To The End). He explains what he means by this: “Mankind is failing that test because mankind has the truth in the reality of Christianity, which is there. This truth has been there for 2000 years, and instead of moving ahead and becoming more widespread it is becoming more restricted.”

But he goes on to say that when the anti-religious are attacking Christianity, it is not the essence pf Christianity they are attacking but their own false reading of it. What is really going on is an effort to restore a mythical pagan world.

Girard reflects that when he was a child, before the invention of the atom bomb priests always talked in church of the apocalyptic texts, particularly before Advent, the last Sunday of Pentecost time. He speaks of how they impressed him. “In a way the inspiration of my whole work is there. I have been talking about these texts all the time.”

“In some way the gospels and scripture are predicting that mankind will fail the test of history since they end with an eschatological theme, literally the end of the world”.

Girard’s calm rational vision of the ‘end times” are reminiscent of what Romano Guardini wrote about the Book of Revelation

“The apocalyptical is that which reveals temporality’s true face when it has been demasked by the eternal. It was given to St. John to behold this. No pleasurable favour, this gift of the visionary eye. He who has it can no longer look upon the things of existence without trembling at sight of ‘the hair’ by which they hang. He lives under the awful pressure of constant uncertainty. Nothing is safe. The borders between time and eternity melt away. From all sides eternity’s overwhelming reality closes in upon him, mounting from the depths, plunging from the heights. For the visionary life ceases to be peaceful and simple. He is required to live under duress, that others may sense how things really stand with them; that they not only learn that this or that is to take place—still less the futile details of the time and circumstances—but that they may possess the essential knowledge of what all existence undergoes at the approach of the eternal. Only he reads the Apocalypse properly who leaves it with some sense of this.”

In exploring the errors of our time and in presenting his interpretation of our true nature Girard seems to be offering us a way out of our contemporary self-destructive maze. What that way is, based on the twin pillars of his study of the process of human desiring and the truly redemptive sacrifice of Jesus Christ which Frazer denied, will be approached in part two of this article.

About the Author: Michael Kirke

Michael Kirke is a freelance writer, a regular contributor to Position Papers, and a widely read blogger at Garvan Hill (garvan.wordpress.com). His views can be responded to at mjgkirke@gmail.com.