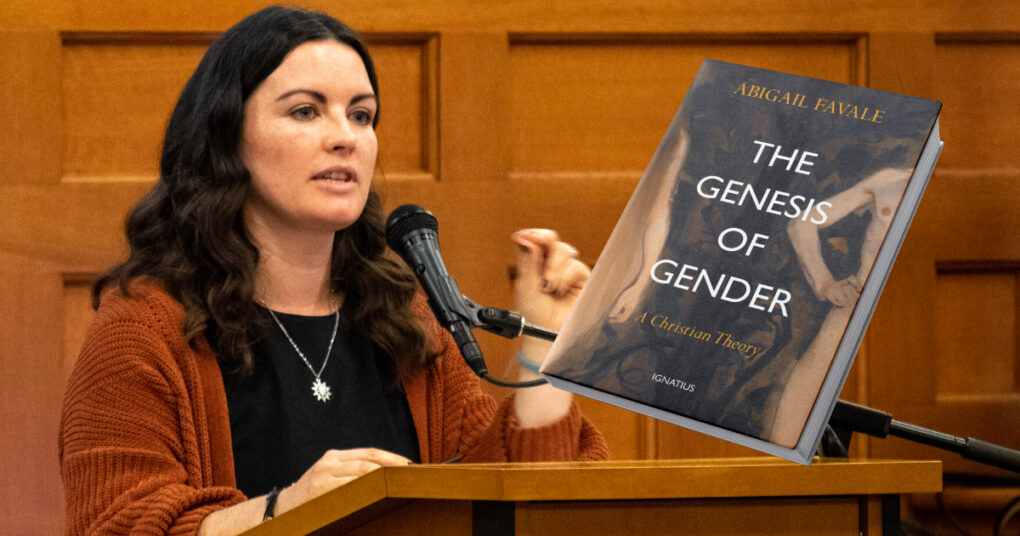

The Genesis of Gender:

A Christian Theory

Abigail Favale

Ignatius Press

June 2022

248 pages

ISBN: 9781621644088

Three particular areas of the author’s areas of expertise combine to make this book a unique contribution to the question of gender ideology: firstly the author’s academic background is in gender studies and she clearly knows it deeply “from within”; secondly she is a convert to Catholicism who has a profound grasp of her faith; and thirdly she is also a fiction writer with a deep artistic sensibility. The book she has written here is a forthright, profound and at the same time sensitive study of the issues surrounding what has become to be known as gender ideology. Not only is she able to explain a rather obtuse topic like gender in very attractive language, but she brings to the discussion the insights of an artist. Some of her observations left me quite stunned.

The book is composed of nine sections, and perhaps the best approach is to simply describe her journey through the course of these nine sections.

1. Heretic

She begins the book describing her realisation – through various “little epiphanies of horror” – that as a teacher of “orthodox” gender theory, albeit at a Christian university, that she had had become an ideologue.

She had begun her university studies as an Evangelical feminist, but gradually was drawn into radical feminist ideology and in particular the of the French postmodern feminist Luce Irigaray. She followed Irigaray faithfully into postmodernist feminism: “As a postmodernist, I focussed all my attention on the inability of human language and understanding to reach out and fully grasp a divine being…. Within this worldview, any claim to authoritative knowledge is simply an exercise in power.”

Importantly she notes that the postmodern rejection of claims to objective knowledge as exertions of power is key to understanding the radical feminist suspicion of the “patriarchy”. Favale, was drawn into this suspicion and found herself beginning to interpret everything, and especially Christian scripture, through a “hermeneutics of suspicion”. She had “become an ideologue without realising it”, and had, in the words of an honest and clear-mind colleague, been “giving students poison to drink”.

However Favale is careful not to engage in a simplistic demonisation of feminist theory. Indeed it was the nuggets of truth she found in postmodernist feminism which actually sent her on the road towards Catholicism. It was through her feminist studies that she discovered the work of Hildegard of Bingen, and at the recommendation of Irigay herself, began to focus on the very Catholic idea of incarnation.

Nevertheless she does point out that if you are an orthodox Christian you are by definition a heretical feminist: “I have to warn you: being a Christian feminist means being a heretic, one way or another. You have to make a choice. Embracing Christian orthodoxy means rejecting certain feminist dogmas.” In this book she seeks to show how the gender paradigm contrasts with the paradigm of Catholic Christianity. The former “affirms a radically constructivist view of reality” – a reality which has no creator, and so no intrinsic meaning; meaning must be imposed on it by man. This of course is especially applicable to the human body itself – its meaning is only what is imposed on it.

2. Cosmos

She contrasts the Genesis account of the origin of the sexes with that of gender theory. The Genesis account is firmly based on the reality of the created order which is produced by God’s love, whereas the gender theories see reality as a “construction” of the mind and human language.

Favale also contrasts the Genesis account with the great ancient creation myth found in the Babylonian epic of Enuma Elish, and also with the Platonic understanding of sexual diversity found in Plato’s Timaeus. Where Plato sees woman as a defective man, the Genesis account shows why sexual difference really matters: through it man and woman bear the image of God, they have a capacity for self-gift, and also exercise a shared governance over creation. This is the plan written into creation by God himself – it is not a human construct.

The original sin is truly a dramatic “fall” from this initial dignity into mortality and shame. In hiding their nakedness, Adam and Eve seek to hide, as Saint John Paul II put it, the sacramental symbolism of the body. The rupture introduced by the sin of our first parents has, through the introduction of concupiscence, problematised our relationship with our own bodies, and with the bodies of others. As Edith Stein observed, Original Sin introduced a master-slave dialectic into our relationship with our own bodies. Hence redemption must include the healing of the relationship between the sexes. The wound of male domination cannot be healed except with divine grace – something that feminists fail to recognise.

3. Waves

Favale summarises the history of the evolution of modern feminism through its three “waves”: from the first-wave feminists of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries who, “for the most part, were not radicals or revolutionaries. Most were middle-class wives and mothers, committed Christians who opposed abortion. Their aim was not to overthrow or subvert the system but to gain legal representation within it.” The second wave is ignited in large part by Betty Friedan’s 1963 The Feminine Mystique – a withering critique of the stereotypical gender roles of the preceding decades. The demand for both contraception and abortion eventually became central goals for second-wave feminists. The third wave of feminism from the 1990s was focussed on uninhibited sexual freedom for men (against that weaker stream of feminism which opposed pornography and prostitution as forces of female oppression) while around 2012 a fourth-wave feminism was less sanguine about unrestrained sexual licence, seeing this, along with racism and sexism as forms of oppression, and – more radically – fourth wave feminism “took the unprecedented step of rejecting the idea that a “woman”, by definition, is a biological female. ”

4. Control

Favale shows how the goals of the feminist movement shifted radically under the influence of Margaret Sanger (1879-1966). Initially the focus of these first-wave feminists was above all on reforming the legal system in favour of women’s rights; they were not proponents of contraception. But Sanger – motivated by her own radical eugenicist goal of purging the world of so many “meaningless, aimless lives” – founded the birth control movement in America. For her, and feminists like Simone de Beauvoir who followed her, a woman’s potential for pregnancy came to be seen as an almost pathological condition to be medically controlled, in particular through contraception and (in de Beauvoir’s case) abortion – and this has become the current medical paradigm.

Ironically and sadly this suppression of female fertility has facilitated the presentation of women as objects of male gratification. Of course for men the notion of depersonalised sex devoid of lasting ties and consequences is facilitated by the fact that men cannot become pregnant. For women things are different: “When freedom-as-choice becomes the open-ended telos of human existence, the body quickly becomes a problem, particularly for women, because our fertile physiology ties us intimately to other bodies and to the rest of creation.” For this reason the contraceptive pill (researched, funded and promoted by Sanger) holds the promise of giving women a share in this masculine autonomy: “‘Take this pill’, says the serpent of the new millennium, ‘and ye shall be as men.’”

5. Sex

Favale analyses the crooked thinking underlying the key theory in gender ideology: that gender is a “social construct”, assigned to a baby at birth (by agents of the patriarchy). To believe that there are in reality two quite different sexes: male and female is, for gender theorists, the heresy of “essentialism”. Thus a schism is created between body and identity, and “Instead of body-identity integration, we are left with fragmentation, a picture of the human person like a Potato Head doll: a hollow, neuter shell that comes with an assortment of rearrangeable parts.”

She compares embracing this ideology to falling down the proverbial rabbit hole: swallowing the notion that sex is not binary but a spectrum leads one invariably to the idea of sex as a social construct “projected” onto a body, and from there to the possibility of changing one’s sex. The extremely rare condition of “intersex” babies: those born with a genuine sexual ambiguity, has been unjustly co-opted to attempt to undermine the essential categories of male and female.

6. Gender

The widespread embrace of contraception during the mid-twentieth century has been instrumental in impoverishing our view of sexuality. Sexuality has been reduced from a substantive procreative function – our generative potential as males or females – to mere sexual appearances. As a result the sexual organs are seen as purely ornamental with no function beyond mere pleasure-making and so can be removed or added at will to match the nebulous “gender” a person claims to experience. It is anyone’s guess what now is meant by gender: “Pop narratives about gender often speak as if gender is something real, even though the concept itself resists the slightest hint of realism – or consistency. Gender is a spectrum! Gender is fluid! Gender is innate! Gender is in the brain! Gender is a construct!”

Ironically, “Now, unmoored from the body altogether, gender is defined by the very cultural stereotypes that feminism sought to undo.” We see this in the extreme, insultingly stereotypical, caricature of women that transsexual men often like to flaunt: all bouffant hair, busty, high heels … the works. The new gender orthodoxy is so inherently fragile that thought and language around gender need heavy policing to ensure the “correct” use of gender pronouns, the avoidance of “misgendering” etc.

7. Artifice

Favale looks at the mushrooming phenomenon of gender dysphoria amongst children, and girls in particular: in less than a decade, gender referrals had increased by almost 2,000% – with this increase being predominantly among girls. And so, “Here is the difficult truth: we are living in an era when our young women are increasingly deciding they would be better off as men.” This, she thinks, is in part “a rebellion, a protest, against the hyper-sexualization of the female body” since our hyper-sexualised culture has “degraded, dominated, depersonalized” women to be level of objects of sexual gratification. And so, “Is it any wonder that our girls are in revolt?” she asks.

The web has played a big part in the phenomenal leap in transitioning, in large part because it facilitates a leap into a fantasy world: “Self-invention in the realm of the internet is limitless. Our online selves are avatars, unbounded by physical circumstances that become inescapable in the world offline.”

In a section entitled “Medicalizing the Body” she describes the really distressing medical realities of transitioning and in some cases subsequent attempts to de-transition. She points to the astronomical costs involved (a million dollars in the case of one transitioner), the grossly irresponsible use of what amounts to experimental hormone therapy on children, and the inconvenient and sometimes devastating effects of transitioning on boys and girls. It all makes for very grim reading.

8. Wholeness

Favale recounts her own harrowing experience of postpartum body dysmorphia and wonders what would have happened had she received the kind of “affirmative” therapy that is de rigueur for sufferers of gender dysphoria:

Why yes, you should be hypervigilant at all times, especially during Mass, just in case a gunman shows up. You are in constant danger; your baby could die at any moment. Yes, your breasts aren’t really part of you since you feel so disconnected from them. In fact, you might consider amputating them, so your reflection doesn’t bother you anymore. And yes, if you feel like you are a terrible mother, I’m sure that you are.

And yet transgender care is a madhouse “which is shaped by ideology rather than sound evidence”. Favale though evidently full of compassion for those experiencing gender dysphoria, is clear that she will not bow to the pressure to use preferred (sex-based) pronouns:

Using sex-based pronouns, rather than gender-based pronouns, is undoubtedly disruptive and likely offensive to most trans-identified people. Such a move could close the door to a relationship with that person from the outset. Yet, if I use pronouns that conflict with sex, I am assenting to an untruth. More than assenting, in fact; through my own words I am actively participating in a lie…. To call a male “she” is a lie, an inversion of the reality that that word names, a reality I happen to belong to, one that I have not chosen, but that has chosen me.

At the same time Favale warns Christians about the danger of coolness towards the individuals who have transitioned and even de-transitioned. She tells the story of a transitioner, Addy, who has developed a great love for the Mass, but has received mixed-messages from Catholics. Favale points out that “It is possible to judge whether an ideology is true or false—but we cannot judge persons; we have not been granted access to the inner chambers of the human heart. Each person’s status before God is a mystery that cannot be known from without.”

9. Gift

In the final chapter Favale recounts the story of Daisy, a teenager who profoundly regretted transitioning and whose choice to detransition coincided with a growing interest in God. Daisy tells her story not as a simplistic moral tale but as the story of something much more profound:

She no longer saw herself as her own creator, responsible for the work of self-fabrication. Once understood as created, selfhood, including one’s sex, becomes a gift that can be accepted, rather than something that must be constructed. This initiates a different orientation to all of reality, even one’s own body: a shift from control to receptivity.

Favale shows how Daisy’s movement from control to receptivity reflects the two divergent conceptions of freedom which dominate our time, and are reflected in the gender debate: “on the one hand, freedom according to postmodernity, an open-ended process of self-definition whose only limit is death; on the other, freedom as an ever-deepening sense of belonging and wholeness, not only within oneself, but in relation to all that is.”

Favale shows how the issues underlying gender ideology are essentially theological, and how the final answer is the Christian conception of one’s place in God’s creation. How one relates to that part of creation which is one’s own body is inseparable from the relation to all of creation, and in particular embodied man: “This book has been largely concerned with the erasure of sexed embodiment and the triumph of disincarnate gender, but that is only one symptom of a broader disease: divesting the human body of intrinsic dignity and worth – forgetting the body as gift.”

•••

I think this book is essential reading for those wishing to understand gender ideology more deeply and from a Christian standpoint. Unfortunately the social contagion of gender dysphoria and request for sex transitioning does not look like abating any time soon. A quick Google search for “gender dysphoria in Ireland” throws up a rake of gender dysphoria treatments available, always “gender affirming”. Sadly many young lives are yet to be ruined before – somehow – this madness abates. Favale’s book is a terrific contribution to a restoration of sanity.

About the Author: Rev. Gavan Jennings

Rev. Gavan Jennings is a priest of the Opus Dei Prelature. He studied philosophy at University College Dublin, Ireland and the Pontifical University of the Holy Cross, Rome and is currently the editor of Position Papers.