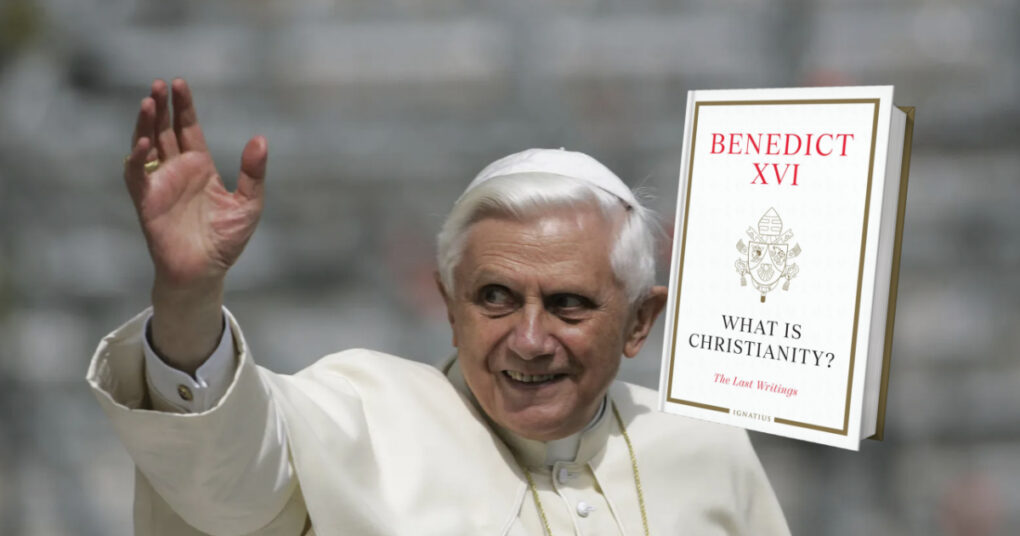

What is Christianity? The Last Writings

Benedict XVI

Elio Guerriero & Georg Ganswein (editors)

Ignatius Press

Aug. 2023

232 pages

ISBN: 978-1621646556

These last writings of Benedict XVI, written during the years of his retirement, show the same breath of erudition as characterise all his work and are composed of various genres. In total there are eighteen texts divided into six chapters. Among the variety of styles there is a scholarly article on the relationship between Christianity and Judaism, published in the theology journal Communio in 2018, which led to a constructive interchange of letters with the chief Rabbi of Vienna which is also included in this volume. There are essays on “Monotheism and Tolerance”, on “The Christian-Islamic Dialogue”, as well as two texts on the liturgy. There are two interviews, one on faith and justification, and the other on St Joseph, as well as several occasional speeches and essays, such as a reflection on the 75th anniversary of the execution by the Nazis of Fr Alfred Delp, S.J. (1907-1945).

The Pope Emeritus himself introduces each of the pieces that make up the volume in his preface, dated at the Mater Ecclesiae monastery on May 1st, 2022. He concludes the preface by saying he has entrusted these texts to Dr Elio Guerriero, to be published after his death. In the foreword, Elio Guerriero records that the Pope Emeritus had written to him: “For my part, I want to publish nothing more in my lifetime. The fury of the circles in Germany that are opposed to me is so strong that if anything I say appears in print, it immediately provokes a horrible uproar on their part. I want to spare myself this and to spare Christianity too” (p. 8).

The first text in these “Last Writings” of Ratzinger/Benedict XVI is: “Love at the Origin of Missionary Work” (pp. 17-23). This message was read on the occasion of the dedication of the renovated Aula Magna of the Pontifical Urbanian University, which was named after Benedict XVI on October 21st, 2014. Here Benedict was revisiting a frequent theme in his theological writings and in his pontifical teaching, and a fundamental question which is still very alive today: Why seek to spread the Gospel? In a pluralistic world does it still make sense to proclaim the Faith? Are not all religions basically the same? “The renunciation of truth seems realistic and useful for peace among religions in the world. Nevertheless, it is lethal for faith”, says Benedict XVI (p. 19). He goes on to observe that all religions in fact await Christ, and “Christ awaits them” (p. 20). Moreover, it is not the case that religions are all the same. There are also negative aspects in some religions (cf. p. 20). Beyond these reasons however, there is a simpler way to justify the task of evangelization: “Joy needs to be communicated. Love needs to be communicated. Truth needs to be communicated” (p. 22). (It might be useful to read this essay in conjunction with the weekly catechesis of Pope Francis on apostolic zeal during 2023 as an example of recent papal insistence on the urgency of evangelization).

Chapter Four (“Topics from Dogmatic Theology”) contains a deep reflection on the Catholic priesthood. Here Benedict sets out to address a wound open since the sixteenth century denial by Martin Luther of the priestly nature of the New Testament ministry. Vatican II did not address this question, and in the years after the council the issue “turned into a crisis of the priesthood which has lasted to this day” (p. 136). Luther’s rejection of the priesthood is predicated on the rejection of the notion of sacrifice, since in his view, “sacrifice is an institution that belongs to the Law, and therefore must be judged negatively” (p. 167). Ratzinger undertakes a detailed analysis of three scriptural texts, each of which held a special place in his own personal meditation in preparation for ordination (Ps 16:5-6, Dt 10:8, Jn 17:17). On this basis he concludes that “a Christological reading of the Old Testament shows that Jesus Christ is also a priest in the proper sense” (p. 140).

“The Church and the Scandal of Sexual Abuse” which comprises Chapter Five (“Topics from Moral Theology”) was a contribution from the Pope Emeritus on the occasion of the gathering of bishops called by Pope Francis in February 2019 to address this crisis. This is a lucid analysis in three parts. The first is a survey of the sexual revolution of the 1960s and its consequences on social life. The second looks on the impact of this upheaval on seminary formation. (In this context he remarks: “Perhaps it is worth mentioning that, in not a few seminaries, students caught reading my books were considered unsuitable for the priesthood. My books were hidden away like naughty literature and read only surreptitiously, so to speak” (p. 185)). The third part is an attempt to plot a way forward. For Benedict the key problem in the abuse crisis is the issue of faith and of the absence of God. He emphasises “one central issue, the celebration of the Holy Eucharist” and adds that “our relation to the Eucharist can only cause concern” (p. 191). Benedict asserts that “if we reflect on what should be done, it is clear that we do not need another Church of our own design. Rather, what is necessary is a renewal of faith in the reality of Jesus Christ given to us in the Blessed Sacrament” (p. 192).

Benedict XVI’s characteristic concern with the priority of God expressed in the proper understanding of the liturgy is present also in “The Meaning of Communion” (pp. 155-174). In analysing the essence of the Mass, he observes that in recent decades “with the disappearance of the sacrament of penance, a functional concept of the Eucharist spread” and that “the understanding of the Eucharist has been protestantized to a great extent” (p. 159). “The most profound reason for the crisis that upset the Church lies in the eclipse of God’s priority in the liturgy”, he states in the Preface to the Russian-language edition of Volume IX: Theology of the Liturgy, of the Collected Works of Joseph Ratzinger-Benedict XVI (p. 57). At the same time, the Pope Emeritus rejoices at the rediscovery of Eucharistic Adoration and of the Lord’s real presence at World Youth Days (cf. p. 159).

St John Paul II appears at various points throughout this book. In a speech expressing his gratitude for the conferral on him of a doctor honoris causa by the Pontifical University of John Paul II in Krakow and the Krakow Academy of Music, Benedict XVI observes that without John Paul II, “my spiritual and theological journey is not even imaginable” (p. 52). In his essay marking 100 years since the birth of his predecessor, Benedict dwelt on the Polish Pope’s focus on the Second Vatican Council: “Vatican Council II was the school of his whole life and of his work” (p. 208). From the start of his pontificate John Paul II had “the ability to awaken a renewed admiration for Christ and for his Church”, because he came from a country where the council had been received in a positive way: “The decisive factor was not doubting everything but rather renewing everything with joy” (p. 209). The central thrust of this reflection however is Divine Mercy, which Benedict identifies as “the real core” and “the essence of the conduct of this Pope” who died on the eve of Divine Mercy Sunday (p. 210).

The final text in this volume is a short interview about St Joseph in the German newspaper Die Tagespost. “His silence is at the same time his message” says Benedict (p. 218). This interview epitomises Benedict XVI. It is sublime and simple at the same time, erudite and full of humanity. In the one breath he offers precise scriptural insights and also recalls how the feast of St Joseph was celebrated in his family home: “Most times my mother, with her savings somehow managed to buy an important book (for example, Der kleine Herder [a small reference book]). Then there was a table-cloth specifically for the feast day, which made the breakfast festive. We would drink fresh-ground coffee, which my father liked very much, although usually we could not afford it. Finally on the table there was always a primrose as a sign of spring, which St Joseph brings with him. And to top it off, Mother would bake a cake with icing, which completely expressed the extraordinary character of the feast. In this way, the special quality of the Feast of St Joseph was tangible from early morning on.” (p. 222).

The assessment of this final book of Benedict XVI by its editor Elio Guerriero seems right: “In short, this present volume is not just a collection of previously published texts with a few new ones added, but rather a kind of spiritual testament written in a spirit of wisdom by a fatherly heart that was always attentive to the expectations and hopes of the faithful and of all mankind” (p. 9).