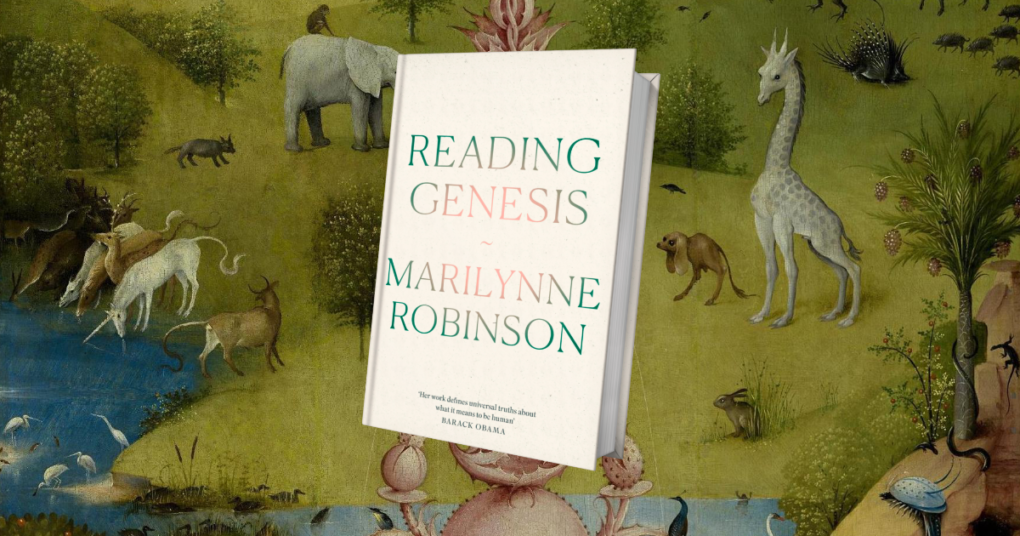

Reading Genesis

Marilynne Robinson

Virago

March, 2024

352 pages

ISBN: 978-0349018744

“Sacred Scripture must be read and interpreted in the same Spirit in whom it was written.” This puzzling phrase from Dei Verbum, the Second Vatican Council’s keynote document about Sacred Scripture, seems to apply to Reading Genesis by Marilynne Robinson. It is a book filled with closely observed facts and insights about the first book of the Bible but beyond that, it allows the Spirit to breathe over it all.

Genesis And Pagan Myths

Marilynne Robinson obviously brings her novelist’s mind to bear on Genesis, and this permits her to bring the characters to life in a very strong way. She is able to combine a theological approach with a keen eye for narrative and many parts of the story come through with a new freshness in her telling.

As she points out, writers on the Old Testament tend to compare the biblical narratives of Creation with the myths of the surrounding cultures. Similarities among them are generally taken to indicate borrowing, and the borrowing to be proof that the biblical texts are derivative, the early chapters of Genesis, as the younger literature, being derived from these pagan tales.

Robinson joins the exegetes in comparing Genesis with two great Babylonian narratives, the Epic of Gilgamesh and the Enuma Elish and she agrees that there are common points between Genesis and these and other Middle Eastern mythologies and stories of creation.

And It Was Good

But the more similarities there are, the more crucial the differences: she points out that the gods of the Enuma Elish suffer hunger, terror and loss of sleep; disasters, battles, pettiness, revenge, etc. It is almost like a heavenly – or hellish – soap opera. Against this background, to say that the God of the Hebrews is the good creator of a good creation is not, she remarks, a trivial statement. The insistence of Genesis on this point, even the mention of goodness as an attribute of the creation, is unique to Genesis. “A Babylonian, drawing on the account of things made in the narratives of his or her religion … might beg to differ. Their gods are fickle, engrossed in conflicts and resentments, indifferent or hostile to humankind” (p.12).

Where she asks, did the relative benignity of the Hebrew cosmos come from? It does not depend on a denial of the reality of evil, which is never far from the surface. Where the God of Genesis is unique, she claims, is in His having not a use for men but a mysterious benign intention for them: “A Babylonian might console herself with the thought that the gods must do as they must do. A Hebrew could say that her God had a great purpose unfolding in time” (p.18). Mercy and forgiveness have a role to play in the emergence of this destiny.

The action of creation is unified by the recurrent phrase “and it was so”, a kind of reverent amazement on the part of the original writer, at the emergence of being out of a formless void. “It is the world we know – the sun giving light to the earth, sea creatures swarming, birds in flight across the heavens; all seen in their wondrous singularity, yet made one in the seven iterations of the word good” (p. 25).

In another interesting parallel to the Second Vatican Council’s document on scripture, she has no hesitation in turning to the unity of scripture, quoting for instance St Paul’s speech in the Areopagus about the “unknown” creator God, in contrast again to the mythical figures abounding in the Athenian temples, and his commentary in Romans on the faith of Abraham.

The Centre Of Creation

The centrality of humankind in the creation myth of Genesis is from the beginning an immeasurable elevation of status, made meaningful in the fact of our interrelating with God even at the level of sacred history. This is unique to the Bible and central to both Testaments. It doesn’t make her gloss over the treachery, murder and intrigue which come to the fore right through the book.

Genesis, however, acknowledges a crucial variable that is not present in the Babylonian ethics: human freedom and culpability. If we could do only those things that God wills, we would not be truly free, though to discern the will of God and act on it is freedom. This is the drama which is played out before us in Noah, the patriarchs, and particularly in the stories of Jacob and Joseph.

Concluding

Reading Genesis is not an easy read: no chapter headings, no concessions to the reader beyond her clear writing style and obvious affection for the Book. In conjuring up the authorship of this and other books of Moses, she imagines a circle of the “pious learned, rabbis before the word, remembering together what their grandmothers had told them, finding the loveliness of old memory in an odd turn of phrase, realizing together that these strange tales sustained a sense of the presence of God that was richly renewed for them in their reverent deliberations…. I take it, that in a wholly exceptional degree, their deliberations found their way to truth” (p.5). This is not far from the spirit which she brings to reading Genesis herself.

About the Author: Rev. Patrick Gorevan

Rev. Patrick Gorevan is a priest of the Opus Dei Prelature. He lectures in philosophy in St Patrick’s College Maynooth and is academic tutor at Maryvale Institute. He has written on the early phenomenological movement, virtue ethics and the role of emotion in moral action.