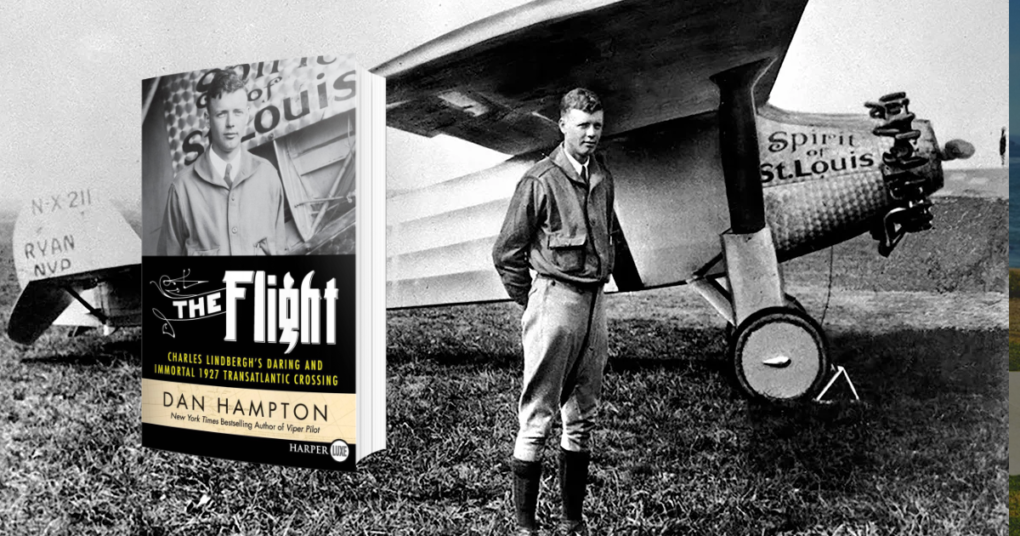

The Flight: Charles Lindbergh’s Daring and Immortal 1927 Transatlantic Crossing

Dan Hampton

Harper Collins

2018

317 pages

ISBN 978-0062464408

This book gives an extraordinarily detailed reconstruction of Charles Lindbergh’s epic flight from New York to Paris in 1927, providing the reader with a view from the cockpit of one of the most daring flights ever undertaken. Because Lindbergh made copious notes describing every possible detail of the flight and kept detailed diaries, the author Dan Hampton (himself a decorated fighter pilot) is able to provide us with an account of the flight and of Lindbergh’s roller coaster of emotions throughout.

Hampton also weaves a lot of personal and social history into the story. From a distance of nearly a century, and from a world where thousands of planes fill the skies, it is hard to imagine the sensation that the early flying machines must have caused. After all the Wright brothers flight took place less than a quarter of a century before Lindbergh’s, and while aviation had developed during World War I and on a smaller scale subsequently (Alcock and Brown notwithstanding), spotting planes flying overhead was still a rarity for most people.

In 1919, French-American hotelier Raymond Orteig offered a prize of $25,000 for the first flight between Paris and New York or vice versa. Unclaimed for eight years, less than a fortnight before Lindbergh’s flight, two of France’s leading aviators, Jules Marie Nungesser and François Coli, took up the challenge. Alas, the Prologue of Hampton’s book ends on an extremely evocative, poignant note when it describes the flight of their plane L’Oiseau Blanc (The White Bird) which started from Paris and flew over Normandy, the south of England and then southern parts of Ireland. Several sightings of their plane were recorded over England and Ireland: the last one at 11 a.m. by an eight year old boy climbing Knocknagaroon Hill near Carrigaholt in West Clare: “The boy watched, transfixed as a large white biplane serenely crossed the shoreline, chasing the sun to the west out over the Atlantic. It was never seen again.”

In the days that followed, Lindbergh finished preparations for his flight and took off in The Spirit of St Louis on his own from Roosevelt Field, Long Island in front of 500 onlookers on Friday 20th May 1927 at 7.52 a.m.

As well as describing in great detail his flight over the eastern States of the USA, Nova Scotia and Newfoundland, the author gives details which the more technically minded reader will relish. One could actually imagine being in the cockpit alongside Lindbergh and privy to his thoughts, and sharing the highs and lows of the journey. It’s amazing that having been unable to sleep the night before, he could summon the reserves to stay awake for the whole thirty-three hour flight. For the first eleven hours he flew over land, but as darkness fell he was flying out over the North Atlantic, and he had never before flown over the ocean.

Despite detailed maps and the most assiduous navigation work he was clearly uncertain as to the location of The Spirit. Having flown through the night, as day broke, Lindbergh – confident he was on course and that Ireland lay several hundred miles ahead – was shocked to see signs of life below and he wondered had he been blown off course to the south or north. He soon discovered that what he had seen were fishermen off the coast of Kerry, in the south west of Ireland.

Unknown to Lindbergh his voyage was being tracked in several countries, so that by the time he flew over the English Channel a crowd, which eventually numbered 100,000, was gathering at Le Bourget Air field, north east of Paris. This made for a very precarious touch down, and death and injury to spectators were only narrowly avoided. In the aftermath of the flight Lindbergh became a hero, a worldwide celebrity and the first person to be honoured by Time magazine as its “Man of the Year.” Tragedy struck later when Lindbergh’s baby son was kidnapped and murdered. He continued to make his contribution to aviation for several decades, though not without a controversial falling out with President F.D.Roosevelt. The book makes no reference to Lindbergh’s extra marital affairs, some of which only came to light after his and his wife’s deaths.

Lindbergh was an honoured guest at the launch of Apollo 11 in 1969, – indeed just forty-two years separated his epic flight and the first moon landing. He developed cancer in 1972 and died in 1974. He was a man of real determination, a loner, single minded like his father and other ancestors. Sometimes it takes single-minded determined people to push back the barriers to progress in science, aviation and other walks of life.

I haven’t flown across the Atlantic since before Covid 19. If I ever do so again, on the flight home I will certainly be re-imagining Lindbergh’s progress over the eastern United States and Canada in his extraordinary flight, and thanking him for paving the way for millions of others to do so.