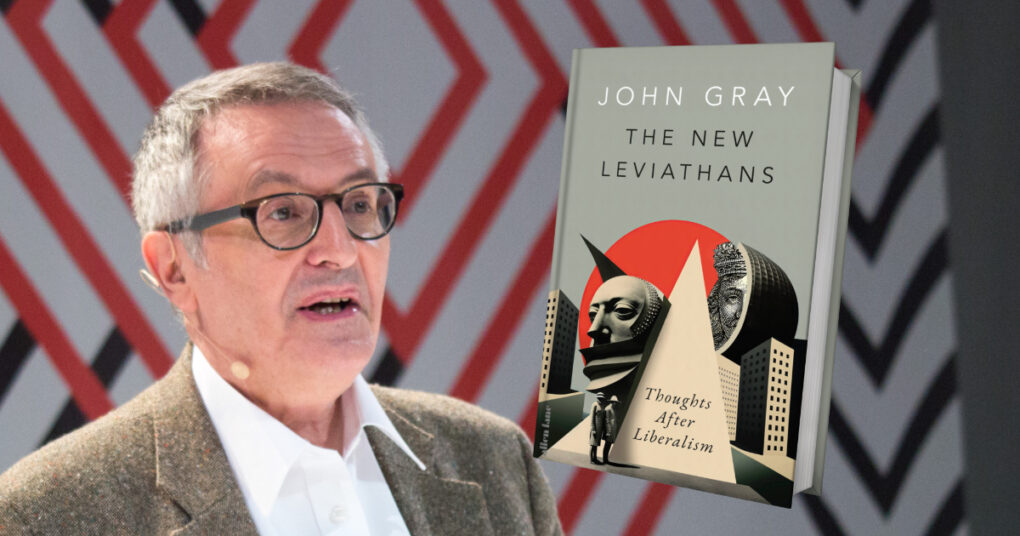

The New Leviathans: Thoughts After Liberalism

John Gray

Allen Lane

Sept, 2023

158 pages

ISBN: 978-0241554951

John Gray is one of a growing number of public intellectuals coming from a non-believing, left leaning background to take issue with woke liberalism. It is interesting that the analysis of such writers tends to be sharper and more scathing than anything that comes from religious, conservative pens. Perhaps, it is the disenchantment and sense of betrayal by those who should be in their ideological camp, but are letting the side down, that fuels their polemics?

It would be a mistake to think that all such dissenters are allies by default of conservatives and people of faith. Many of the heavyweight commentators we have become accustomed to hearing, despite eloquently deconstructing and ridiculing wokist follies, remain at best ambivalent about faith. Some indeed, like Jordan Peterson, Douglas Murray and Tom Holland, open-mindedly and respectfully engage with Judaeo-Christian thought and values and acknowledge its foundational role in western societal organisation as well as its rich legacy of thought and art. Others like Ayaan Hirsi Ali and Mary Harrington have connected or re-connected with the Christian faith.

John Gray, however, while acknowledging that liberal values are rooted in Christian thought, remains unswervingly mired in a nihilistic atheism. A widely published political philosopher, regular contributor to The Guardian and The New Statesman, he retired as professor of European Thought at the London School of Economics and Political Science in 2008. Since then he features in podcasts and public debates and is without doubt a force to be reckoned with. His erudition, as this book demonstrates, is extensive though selective. His eloquence is captivating which makes his writing both accessible and compelling and mitigates his profoundly bleak vision of human nature and its future.

The title of the book references Thomas Hobbes of course and the reader journeys simultaneously with the thought of both Hobbes and Gray through the book. In addition to Hobbes, numerous other prophets of gloom pop up over this content packed 158 pages. They mostly come from the erstwhile Soviet sphere. Others cited frequently include Dostoevsky and German philosophers, led by Nietzsche. Not infrequently, the gloomy, jaundiced accounts of our race darken into chilling anecdotes of horror and revulsion prompting the reader to conclude that while life may not be quite so “short” in today’s society, our existence is still as “nasty and brutish” as it was for Hobbes. We hear nothing from thinkers who challenge this portrayal of the human person as “an animal” distinguished only from other animals by an “awareness of mortality”. This dark portrayal simply does not align with human history in its totality, nor with the experience of, perhaps the majority of us, whether humble souls or great thinkers.

For Gray, like his many mentors and guides, there is no grace. Human nature as Hobbes depicted it is incorrigibly bent towards anarchic self-pursuit. Only a Leviathan, a powerful government be it monarchic or parliamentary can keep a degree of order sufficient for humankind to co-exist, not so much “in peace” as Gray puts it, but in a sort of “truce between the human animal and itself”. Gray, however, despite being a confirmed atheist, reserves his scathing denunciations for woke culture. In fact, in this book, he directs no attacks at religious tradition, something that distinguishes him from evangelising atheists like Richard Dawkins, Steven Pinker and others. He takes issue, incidentally, with Pinker for believing that human history follows an arc of progress, thanks to Enlightenment ideas, science and technology.

Gray’s closed and jaundiced view of humanity makes an unusual contrast with the jaunty, pithy and astute observations he makes about so many of the hot topics of our time, views that will resonate with those who hold diametrically opposed positions to his on the question of faith, grace and redemption. He acknowledges that “Liberalism was a creation of Western monotheism and liberal freedoms part of the civilisation that monotheism engendered.” He goes on to add that “21st Century liberals reject this civilisation while continuing to assert the universal authority of a hollowed out vision of its values.” The American founding father, John Adams, had already followed Gray’s logic to its corollary and more satisfactory conclusion when he wrote “our Constitution was made only for a moral and religious people. It is wholly inadequate to the government of any other.”

Gray makes the interesting observation that “values unmoored from their theological matrix become inordinate and extreme”. He does not develop this insight but readers of faith will realise that the pivotal Christian values of mercy and forgiveness have broken loose from the ideological matrix of woke dogma. Gray also notes that the values of secular liberalism have become grotesque distortions, even contradictions, of their original expressions in religious teaching. “While gleefully conniving at the destruction of traditional morality, (they) are pitifully unprepared for the savagery that ensues when it breaks down.” “They don’t desire the good, the good is whatever they desire.” Is this not a tacit acknowledgement that objective good exists and is known to humanity? Here Gray has moved the dial somewhat on Hobbes’s statement, which Gray quotes, “their moral philosophy is but a description of their own passions”.

Gray identifies other factors at work in the misshaping of traditional values. Wokism is an enterprise as well as an ideology, “a career as well as a cult” and like any enterprise it must reinvent itself to stay relevant. Hence, the emergence of ever new classes of “oppressed” groups and sub-groups, all needing to be championed by an expanding network of agencies and services, underwritten by public funding. Gary succinctly describes these self-serving accretions on the body politic which we are so familiar with in Ireland, as “a swollen lumpen intelligentsia (which) has become a powerful political force”.

In a tangential observation, Gray names climate agencies in the context of vested interest and politically motivated activism. “Renewable energy” he writes “is a fossil fuel derivative. Transition (to clean energy) is a chimera.” It’s the carbon belching manufacturing hubs of China who make windmills, batteries and solar panels for the virtue signalling First World. He also points out that the energy needs of “the metaverse”, which we tend to think of as immaterial, is “intensive”.

For Gray, the ideology of individualism which evolved through the history of thought has reached its endpoint in our time in the politics of identity and choice. Quoting Dostoevsky, he writes, “the logic of unlimited freedom is unlimited despotism”. G.K. Chesterton framed the same point from a faith perspective when he wrote, “if men will not be governed by the Ten Commandments, they will be governed by ten thousand commandments.” Thinkers like Adams and Chesterton and so many more before and after them of similar outlook don’t engage the interest of John Gray whose extensive erudition is arguably directed by confirmation bias.

Within the sphere of his worldview however he is sharp and original. He is however not always open to following the pathways of his arguments beyond a certain point. In stating “the story of history is not one of progress”, he does does not acknowledge that it may actually be one of regression in our time, nor that the seedbed of that regression is the rejection of the traditions, values and beliefs that have led our western civilisation to a remarkable degree of civic stability, personal autonomy, collective optimism and artistic and intellectual flourishing, all of which are unravelling within a single generation.

As Gray sees it, every vista of advancement has been a chimera, one Utopia after another, a succession of false dawns. Only the Leviathan of absolute rule offers a solution for our ungovernable race. Over the vast murky, churning, chartless wastes of human existence the only hope is Leviathan. We are but advanced animals distinguished from others only by the “awareness of mortality that leads us to seek immortality in ideas.” “The moth eaten brocade of hope” as he puts it, is rolled out again and again as new ideologies spring into being. He misses the point that for those whose lives are faith centered, not only is there is no such futile searching, but there is a deep inner peace of being. Its source is not, as he postulates, our “awareness of mortality” but rather of immortality, intimations of which are pre-religious and in the very depths of what it is to be human.

There is a great deal more of interest to be drawn from this remarkably short and well written book that even a lengthy review can’t do full justice to. Gray speaks to our times in a thought provoking and challenging way and forces us to engage critically with our own convictions. He makes a lot of assumptions and claims that simply don’t hold up against a wider reading of human history as well as the personal experience of those who live within a culture of living faith.

Books like Gray’s are useful in strengthening and confirming our convictions and equally importantly arming us with better responses to wokist zealots, illiberal liberals, who would rob us of a voice in the public square and beyond, even in the privacy of personal communication and thought. For a Catholic book club this could be a very interesting and worthwhile reading choice.

About the Author: Margaret Hickey

Margaret Hickey is a regular contributor to Position Papers. She is a mother of three and lives with her husband in Blarney.