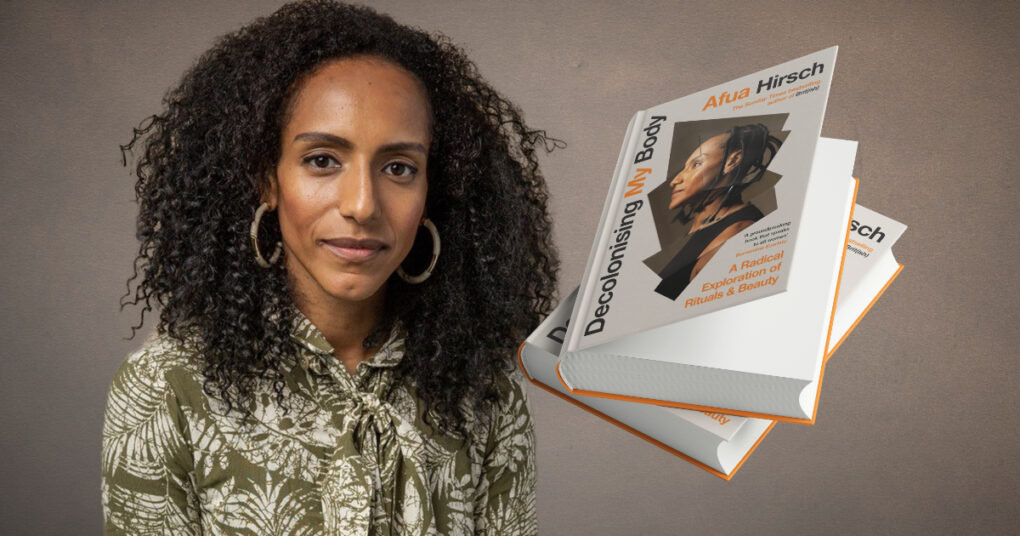

Decolonising My Body: A radical exploration of rituals and beauty

Afua Hirsch

Square Peg

October 2023

184 Pages

ISBN: 978-1529908664

Afua Hirsch is an Oxford graduate, broadcaster, Guardian columnist and Wallis Annenberg Professor of Journalism at the University of Southern California. This is her second book. Her first Brit(ish) was an acclaimed bestseller. My guess is that her second will be a similar success. It weaves the appeal of a personal story around the perennial, mostly female, obsession with how we look to others and how we are judged as a consequence. Because the book is the work of a public commentator and media personality, it also carries the promise of some definitive insights on the subject.

Not surprisingly, Hirsch’s book eagerly taps into the current controversies around identity, marginalization and multiculturalism. Her personal story grants an insider’s view of some of the emotional dynamics driving this charged aspect of our current culture wars. According to her narrative, Hirsch always felt an outsider in the country of her birth because of her African looks. Growing up in Britain as the mixed-race daughter of successful professionals, she enjoyed private schooling and a comfortable middle-class home life in leafy London suburbs. Yet she felt alienated. Acceptance was only possible when her friends could overlook the colour of her skin. “We don’t think of you as black,” was the comment of one friend in her private school in Wimbledon.

Heard through Hirsch’s ears, we can see how the well-intentioned compliment was back-handed, affirming and undermining at the same time, accepting her personally while rejecting her ethnicity and ancestry. The message for her was that she would never pass in her country unless people could look beyond her skin, and transcend their inbuilt attitudes to people categorized broadly and collectively as “black.”

It is easy to imagine how a question like “where are you from?” can demoralize a young person who is immersed in the culture of their country of birth, has never visited their ancestral country, and may know very little about it. Hirsch acknowledges her parents were and are very “westernized.” One suspects that her maternal grandparents, who fled Ghana after its independence in 1957, were even then westernized (or colonized, as she might prefer to say), to the point that life in Britain promised to be more comfortable for them than in their newly independent homeland. She does not delve into this part of her backstory enough to answer this interesting question.

Afua Hirsch has a daughter, who wears “hoodies and jeans” and is reluctant to wear the tribal jewellery her mother offers her. Hirsch appears to be sandwiched between two generations who, unlike her, do not resent assimilation, to whatever degree, into western ways. In fact, Hirsch herself seems to feel racialized in the Ghana of her maternal ancestors, perhaps as much as she does in the country of her birth and upbringing. This is something that strikes one from the start of this book where Hirsch kicks off with a gush of admiration for the phenomenally successful US broadcaster Oprah, who shares her sense of having to struggle against “racialization” as a woman with African roots.

Besides Oprah, Hirsch name checks the pop star Rihanna, another black icon of resistance to “white supremacy.” One could argue that her self-belief as a descendent of the African diaspora would be better bolstered by female public figures with intellectual heft who share her heritage though not her experience of marginalization. One thinks of prominent British politicians like Kemi Badenoch and Suella Braverman, and the woman dubbed by Christopher Hitchens as “the most important public intellectual ever to come out of Africa,” Ayaan Hirsi Ali. She overlooks these women, who share a similar backstory, to identify instead with an American-inflected discourse that is heavily invested in divisive, recriminatory identity politics. In America too, of course, she could have found articulate, influential public female figures like Candace Owens who do not perceive their racial identity as any sort of hindrance to inclusion and advancement.

The way Hirsch positions herself here is just one of the many things in this book that point to deep personal insecurity rooted in a sense of grievance and thwarted entitlement. Why this is so relates more to her personal story and the ideological influences that shape her, rather than the systemic “brutal discrimination” she cites but never details. It explains the appeal of some contemporary black commentators who, like her, identify with the narrative of exclusion and victimization.

Hirsch’s sense of grievance stretches in many directions. Her attack on cultural appropriation is frankly ridiculous. It extends to taking issue with white Europeans buying Moroccan rugs without due appreciation of the stories and symbols woven into their patterns or the hours of manual work involved. One might say the same thing about Aran sweaters and any number of other ethnic-inspired products. In a multicultural world, intercultural appropriation can only be one way for her. Hirsch may resent and sometimes reject western norms of dress, grooming and beauty, but she has embraced the opportunities and freedoms that living in western culture has brought her. Her path to relative affluence and influence was paved by an Oxford education, something she never once mentions in her book. She chooses to live in the western world while purposefully exploring and adopting styles of dress and adornment, which include tattoos, body piercings and scarification, as well as religious rituals and rites of passage practiced by her Ghanaian ancestors.

Hirsch considers that everything the European powers brought to Europe, including Christianity, were without exception bad and often malign. She ignores, but presumably cannot be oblivious of, the legacy of healthcare and education established by religious foundations which continues to this day throughout Africa. In her pursuit of ancestral ritual and belief – “ancient knowledge systems” – she believes she has opened a more congenial portal to the numinous. For her, the moral code of Christianity is repressive. She downplays things like child marriage, bride purchase and female genital mutilation in African culture and never considers how Christianity brought a positive influence to bear in challenging such practices, along with polygamy which she never even mentions.

Everywhere Christianity encountered paganism from its place of origin in the Middle East to the far-flung lands of Asia, western Europe, and South America, it disrupted the very same kinds of cultic practices. Africa’s progress from a pagan past to Abrahamic faiths is far from unique. The continuing growth of Christian churches in Africa and Asia, and among their diaspora elsewhere, suggests religious belief is as good a fit for the African psyche as for any other people it won from paganism.

Everything negative in human development is laid at the door of “white supremacy.” Now the former colonizers are bringing the evils of capitalism, globalization, rampant consumerism, and the attendant climate crisis to Africa and the rest of the world. Strangely and naively, Hirsch welcomes the expanding role of China in African development because it “breaks the stranglehold” of Europeans. The fact that China is the main driver of carbon emissions and mass production of consumer goods does not seem to register with her. Similarly, the tendency of economic, political and social systems, and the discoveries of science and medicine, to emerge first in developed societies, before advancing nations appropriate them, is overlooked.

Hirsch follows the woke doctrine that mainstream culture must cede its space to minorities whether ethnic or sexual. It’s the idea behind the rainbow logo. All bands are the same width irrespective of how populous the groups they represent may be in the real world. The point in woke thinking is that there are no norms. Well not quite. That doctrine itself is the one norm you cannot gainsay without being branded exclusionary under one heading or another.

Hirsch offers a striking example of her understanding of how exclusion works. On a hiking trek to Norfolk with two other women of colour, she resents the deeply embedded Englishness of the area. We should note the part of Norfolk she visited is close to one of the royal residences at Sandringham. It has historic links to England’s, as opposed to Britain’s, past, which place names such as Bury St Edmunds and King’s Lynn attest to. Hirsch takes this Englishness as a personal affront. “The pastoral image of Britain is rife with exclusion.” The problem for her is that Britain is just too British, or more correctly in this context, that England is too English. She does not consider how all minorities feel more or less as she does in countries where their culture is not mainstream. It would be the same, no doubt, for a person of British or any other origin in today’s Ghana. It even appears to be so for herself with her Ghanaian heritage.

Hirsch is oblivious to the fact that her woke mindset places her very much in the ideological mainstream in the western world. One can just as easily be part of a minority for ideological as much as for cultural or ethnic reasons. The place of Christians in their own heartlands is increasingly uncomfortable, even dangerous – not just in terms of the prevailing ethos of non-belief, but also more tangibly in the restraints that a hostile ruling class is prepared to apply through force of law.

Like it or not, there is always a dominant culture, whether of opinion, belief, language or custom. The most any minority can demand is that society does not discriminate against them or purposefully undermine their sense of identity. It is also imperative in a developed society that minorities are made to feel welcome.

This book is written in a chatty and lively style and draws the reader into taking a view of the world through the eyes of a highly educated and intelligent woman who genuinely feels systemically disadvantaged because of her race. It is also somewhat irritatingly smug and self-justifying in tone, and walks blithely by the many questions and counter-arguments that come readily to mind as Hirsch ploughs on, blinkered by the bias of a well-nurtured sense of victimhood. The other half of her personal family story is scarcely alluded to. As the daughter of a German Jewish father, whose gifted family were welcomed to Britain from pre-war Germany, surely there is a very different narrative of immigration and integration to be told? Her scientist granduncle, Sir Peter Hirsch, was honoured by the British government. That story is one we are unlikely to hear from a woman so deeply saturated in the politics of exclusion.

About the Author: Margaret Hickey

Margaret Hickey is a regular contributor to Position Papers. She is a mother of three and lives with her husband in Blarney.