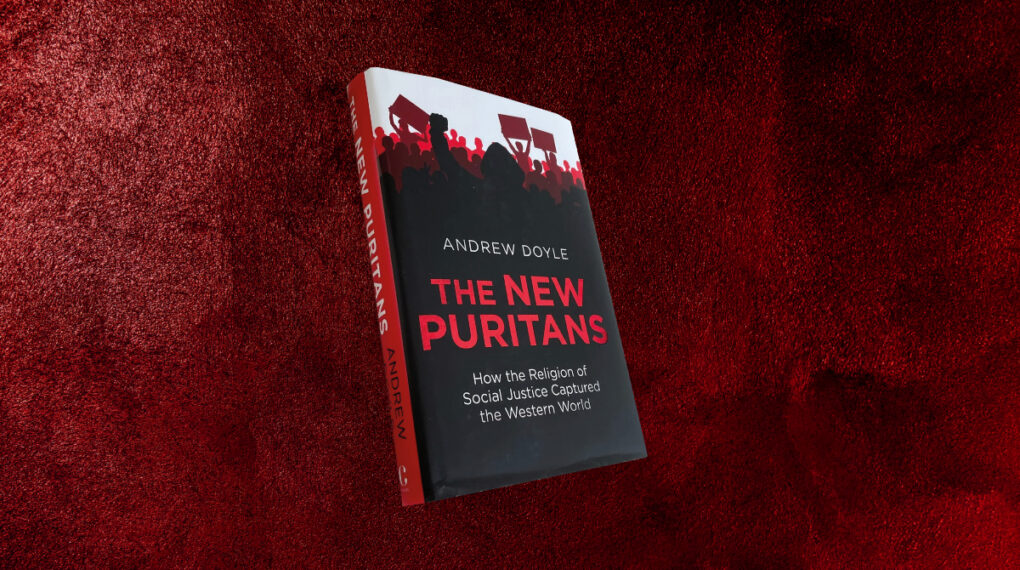

The New Puritans: How the Religion of Social Justice Captured the Western World

Andrew Doyle

Constable

Sept. 2022

384 pages

ISBN 978-0349135328

Once upon a time a “dog whistle” was an object used for training man’s best friend. A “gaslight” illumined the streets of our cities. An intersection was American English for a crossroads. And the intricacies of pronouns were known only to linguists and language learners. Today these words, along with many others, have gained new and potent meanings. If you find yourself struggling to make sense of this new jargon then Andrew Doyle’s The New Puritans might be for you.

A comedian and journalist, Doyle currently hosts a weekly news analysis and commentary program on GB News. The variety of his own career to date bears apt witness to his book, as it defies any attempt at puritanical categorisation. Born in Derry, Northern Ireland, and hailing from an Irish Catholic background, Doyle completed most of his formal education in England, eventually gaining a doctorate in Renaissance literature from the University of Oxford. A vocal Brexit supporter and a “small-c” conservative on some issues, Doyle backed Jeremy Corbyn, the radically left-wing, Remainer, Labour leader in the 2017 general election. Doyle is gay and a long-time proponent of same-sex marriage, but is also strongly critical of the increasingly censorious and authoritarian LGBT+ movement. The many-sided nature of Doyle himself typifies quite well why our contemporary tendency toward reductive labelling is so unhelpful.

Doyle is probably best known for his alter ego, Titania McGrath, a parody social media persona that highlights and satirises the excesses of “woke” thinking. Indeed Doyle has published books under McGrath’s pseudonym and, prior to Elon Musk’s buyout, the account itself was banned by Twitter for hate speech on a number of occasions. However sometimes there is no such thing as bad publicity – Titania McGrath currently boasts over three-quarters of a million followers, and continues to post amusing takes on the culture wars.

The New Puritans opens by recounting the evening a friend left Doyle shaken when he turned on him and branded him a “Nazi”, among other, more indelicate expletives which I shall leave the reader to discover for themselves. This moment proved an awakening for Doyle. His friend was willing to forego their bond due to Doyle’s countercultural views on some issues.

That a difference of opinions should cause a friendship to break down highlighted to Doyle people’s growing implacability in their opinions, and how this was affecting the healthy relationships that a society needs in order to function properly. He identifies this group of culture war ideologues as “new puritans.” While the term does not exactly trip off the tongue, Doyle uses it to describe them throughout his book, and its use seems to have grown increasingly commonplace today.

The book’s opening chapter takes us back in time to the Salem witch trials, when the “old” puritans of seventeenth-century Massachusetts, goaded by a wave of popular hysteria in their community, condemned innocent women to their deaths. The unyielding, single-minded convictions and proto-activism of these censorious villagers casts its unhappy shadow over most of the The New Puritans. Over twelve chapters, Doyle takes the reader on a journey through the worst excesses of today’s culture wars.

Doyle leaves no stone unturned. Those seeking a primer on today’s cultural flashpoints need look no further – intersectionality, privilege, hate speech, pronouns, trans issues, critical race theory, cancel culture, cultural appropriation, memory-holing, censorship, lived experience, and gaslighting, among others, are covered. The book offers helpful historical context for many of these terms. This is valuable insofar as it shows that these phrases generally did not spring out of nowhere, or simply materialise from the voluminous churn of Twitter arguments. Rather, they often emerged from legitimate, though very niche, scholarly debates in recent decades.

For instance, Doyle describes how the term “woke” in fact began “in African-American vernacular during the early twentieth century to signify an alertness to injustice, particularly racism.” Since then, it has snowballed into a catch-all phrase including extreme views that many an African-American from a century ago would struggle to identify with their cause. The term “microaggressions” was coined by a psychiatrist in 1970. Critical race theory has its roots in postmodern legal theory. “Lived experience” stems from a phrase coined by Simone de Beauvoir in 1949. How all these obscure terms wriggled free from turgid and impenetrable academic prose and into the popular lexicon in the space of little more than a decade is a fascinating question and worthy of an anthropological study in itself. However Doyle does not go there, merely adding some context to their existence, and reporting the uses and scenarios that these words find themselves in today.

Doyle devotes an early chapter to exploring the hegemonic status of Marxism, the Frankfurt School, and postmodernism in our educational institutions, which have inevitably spilled over into other fields as graduates have entered the world of work. “Although the new puritans prefer to trace their lineage to the postmodernists,” he argues, “the cultural emphasis of the Frankfurt School is of great significance when considering the development of these ideals. […] Critical Social Justice bears the DNA of Marxism, most notably the utopian belief that equality of outcome is both desirable and possible, even though its realisation would take the implementation of totalitarian measures.” Doyle is clear that there is no great conspiracy motivating today’s institutional and cultural consensus: “most of those who have contributed to the climate of intellectual conformity in higher education have done so unwittingly.” Rather, Doyle finds a Foucauldian desire for power and influence: “What we are seeing is not so much a coordinated march through the institutions as evidence of the appeal of authoritarianism.”

In a later chapter Doyle explores how woke culture has interacted with, and ultimately distorted, the application of law, particularly in the form of opaque “hate speech” legislation and the Orwellian concept of a “non-crime hate incident.” This will be of particular interest to readers in Ireland, whose parliament is currently attempting to pass an extensive and controversial hate crimes bill. Doyle teases out the intricacies, highlighting “the false premise that defending the speech rights of unpleasant people amounts to an endorsement of their words.” He likens modern hate speech legislation to once-prevalent blasphemy laws.

Focusing on the potentially far-reaching nature of Scotland’s 2021 Hate Crime and Public Order Act, Doyle contends that in today’s paradigm, in which words are unduly powerful yet infinitely malleable, “our complicity [in a possible hate crime] does not depend upon our consciousness; our words, ideas, thoughts and actions are products of an unjust system, one that we cannot therefore help but unwittingly reproduce. In this schema, intention is irrelevant.” Ultimately the danger of such legislation is that “hatred is a matter of perception and not intent.” Doyle turns to Solzhenitsyn to warn us of the dangers of censorious overreaching by government and police. The survivor of the Soviet gulags urges the reader that “the simple act of an ordinary brave man is not to participate in lies.”

The New Puritans offers many more descriptions, insights, and anecdotes into the increasingly complex lexicon of modern life. Doyle is far from a non-partisan spectator here. The new puritans, as he calls them, “deserve to be laughed out of existence.” His straight-talking tone is probably rooted in his own background as a comedian and television pundit – neither of these fields indulge subtlety. Unfortunately one drawback of the book’s polemical tone is that it sets inevitable limits on the scope of its argument: no chapter gets particularly deep. Far from transcending contemporary narratives in order to critique their philosophical and sociological underpinnings and motives, Doyle wades right in and presents fascinating and alarming snapshots of life from the trenches of the culture wars.

Furthermore, while the book highlights some of the absurdities and downright alarming developments of woke culture’s worst excesses, it would be a mistake to assume that Doyle is a friend of faith and tradition either. At one point he argues that “the right to criticise and ridicule religion has been increasingly under threat.” Elsewhere, he likens the whole “woke” movement to faith, arguing that “Critical Social Justice is every bit as mirthless as the Christianity it has usurped.” These throwaway moments throughout the book offer glimpses of Doyle’s own outlook: Christian values have been replaced, unprecedentedly rapidly, by an entirely different set of values. But Doyle, one suspects, would rather have neither.

In some (albeit unintended) ways, the book offers an interesting foil to Francis Fukuyama’s 1992 classic, The End of History and the Last Man. Admittedly the two are very different: one is a work of political science, the other a commentary on contemporary culture. Looking back on the three decades since its publication, however, Fukuyama’s presumption that human progress had reached its pinnacle and endpoint with the triumph of Western liberal democracy seems rather naive today. By 1992 the Soviet Union had fallen and contented citizens across the West slumbered in the drowsy indolence of the pax Americana. Life was good in the nineties. But the intervening years have not been kind to this worldview: the rise of China, increasing Russian aggression, collapsing birth rates in Western nations, stagnating working and middle class incomes, and the sting of inflation in recent years suggest that history definitely has not ended.

Doyle’s book betrays a certain naiveté in this regard. At times, while reading it, one is left with the impression that he would like the Western liberal consensus of the nineties and noughties back – that history should have ended then. This period seems to represent the peak of societal attainment for Doyle: socio-economic inequalities of opportunity were being addressed, race relations seemed relatively calm by today’s standards, and many Western nations were on the cusp of making gay marriage a legal reality. But the plates have shifted, and the one-time alignment that found the West’s political, media, and social establishments in a mutually understood liberal synchrony is no more today.

So who is this book written for? The New Puritans offers an exhaustively thorough primer on our current cultural condition. For those with an interest in the culture wars, or who simply want to get up to speed with the latest jargon, Doyle’s book is a great place to start. It is commendably comprehensive in this regard, its vignettes of some of the culture war’s excesses at times alarming, but always engaging.

On the other hand, clocking in just shy of 400 pages, including extensive and commendably thorough endnotes, some readers may find themselves asking existential questions of their own. Like how important is it to know about “dog whistling” or “gaslighting” or “cultural appropriation” or the many other terms that comprise this ever-growing and ungovernable lexicon? Knowledge is power, yes. But equally, ignorance is bliss.

About the Author: David Gibney

David Gibney is a school teacher in Dublin. He holds a Ph.D. in English literature.