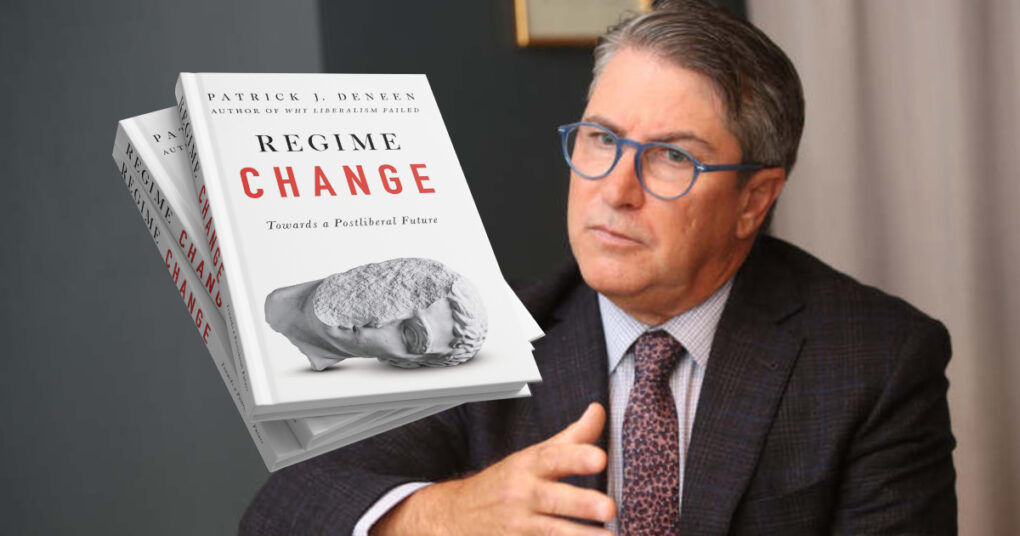

Regime Change: Toward a Postliberal Future

Patrick Deneen

Bantam Press

6 June 2023

256 pages

ISBN 9780593086902

Regime Change: Toward a Postliberal Future by Patrick Deneen is the follow-up work to the University of Notre Dame professor’s influential 2018 work, Why Liberalism Failed. In that book, Deneen had castigated the prevailing liberal political philosophy for placing too much emphasis on individual autonomy, thus sowing the seeds of its eventual decay amidst rising public discontent across the ‘liberal democracies.’

Along with other thinkers such as Sohrab Ahmari and the Israeli-American academic Yoram Hazony, Deneen has risen to ever greater prominence as one of the key figures within the post-liberal movement, whose leaders are particularly critical of the failure of the centre-right establishment to challenge liberal orthodoxies in the economic or social sphere.

Regime Change is more forward-looking and more prescriptive than Deneen’s last book. Having already laid out his case against the status quo, here Deneen argues in favour of what should replace it. “What is needed, in short, is regime change – the peaceful but vigorous overthrow of a corrupt and corrupting liberal ruling class and the creation of a postliberal order in which existing political forms can remain in place, as long as a fundamentally different ethos informs those institutions and the personnel who populate key offices and positions,” he writes, before specifying that the best hope for success in this project is what is generally labelled the ‘new right.’

Without needlessly retracing his steps in ‘Why Liberalism Failed,’ the author provides a succinct overview of his criticisms of liberalism. Of foremost relevance is his assertion that liberals are instinctively hostile to social institutions other than the state. According to Deneen, the advance of liberalism has entailed the “weakening, redefining, or overthrowing of many formative institutions and practices of human life, whether family, the community, a vast array of associations, schools and universities, architecture, the arts, and even the churches.” “In their place, a flattened world arose,” he writes, “the wide-open spaces of liberal freedom, a vast and widening playground for the project of self-creation.”

In addition to being hostile to autonomous social institutions, today’s liberals are also averse to tradition, not least of which are the customs and norms which have been disregarded and condemned in an era of greater social permissiveness.

Deneen notes the groundbreaking work of Charles Murray which demonstrated how a vast chasm now exists between the lifestyles enjoyed by wealthier Americans and those endured by those in lower income brackets.

Today’s political and social power elite is different, the reader is told, due to its “studied placelessness” in a world which is more technologically interconnected and where the powerful base themselves in communities which are fiercely economically stratified. In such an environment, members of one country’s elite are more similar to their counterparts overseas than they are to their own compatriots. This social distance can also give rise to an authoritarian instinct to enforce various (and often ill-informed) diktats, as experienced during the pandemic. The goal of breaking down the barriers within national communities – the realisation of “an alignment of the elite and the people, not the domination of one by the other” – is a core theme throughout.

Before he describes the cure to the ailment, the political philosopher diagnoses some of the root causes. To him, classical (or centre-right) liberalism, progressive (or centre-left) liberalism and Marxism all share the belief in advancing transformative progress, which is often directed against traditionalism. He singles out John Stuart Mill’s opposition to “the despotism of Custom” as an example of the liberal mindset, and contrasts this approach with the cautious attitude to social change demonstrated by iconic conservative thinkers like Edmund Burke and Benjamin Disraeli. Casting his analytical eye back to the ancients, he notes Aristotle’s concerns about the consequences of a concentration of wealth and power among an elite class.

Classical liberalism (which in the modern context can be understood to refer to most centre-right political parties, such as the Republican Party in the US or the British Tories) stands for little except a slower pace of social change in Deneen’s view, and so a new political framework is required.

Though he is clearly aware of the flaws of Donald Trump, he holds out hope that new emerging forces on the right will allow for “the application of Machiavellian means to achieve Aristotelian ends.” To bring about ‘regime change,’ Deneen proposes an ambitious package of political, economic, educational and social reforms. Much of this sounds admirable, including the introduction of German-style workers’ councils to increase the influence of employees and the refocusing of the economy towards a model where a family can be supported on one income.

As an American college professor, he is well-placed to observe that far too many young adults are being channelled towards the university route, and he argues instead for a major expansion of vocational education. Other policy suggestions appear to be inspired somewhat by nostalgia, as with his emphasis on the need to support domestic manufacturing – where nationalist conservatives often confuse a decline in employment numbers to a decline in actual output.

Even more unrealistic in the current cultural context is his call for pornography to be banned. Indeed, Deneen hits upon a key problem confronting his own analysis when noting that in the calmer 1950s, the “ethos of the ruling class itself was broadly in line with the values and ethos of a broad working and middle class.” While there is certainly evidence of a divide between the upper and lower-classes in America and Europe on issues such as mass immigration, it remains the case that the moral values (or lack thereof) of the elite are sadly reflected by those occupying the lower rungs of the socioeconomic ladder.

Religious practice and community participation rates generally reach their nadir here, and the working-class does not deserve false romanticisation by the postliberals any more than they deserve condescension or scorn from the ruling class. Absent a cross-sectoral religious revival in the post-Christian West, there will be no societal return to conservative social mores, something which populist conservatives like those within the Italian government appear to recognise themselves.

Deneen is on safer ground when it comes to his proposals for a mixed constitution and mixed society, calling for the decentralisation of government institutions from Washington DC, the development of satellite elite college campuses in poorer communities and the introduction of national service programmes to force the better off to encounter social communities outside the limited number of areas where they usually tend to converge to live, work and study.

Patrick Deneen is a brilliant political thinker, and Regime Change provides observers of current political upheavals with a compelling philosophical insight into the origins of these tumultuous developments. In America (which Deneen focuses on strongly) the emergence of new right-wing forces has not led to “a rediscovery of early-modern forms of conservatism” which the author hoped for. Nor has the track record of similar European movements been particularly impressive.

Rather than being a roadmap for achieving the unachievable, Regime Change could best be looked at as a prescient warning to established political forces which seem intent on alienating their voters by embracing a misguided progressivism and accelerating down the pathway to societal decay.