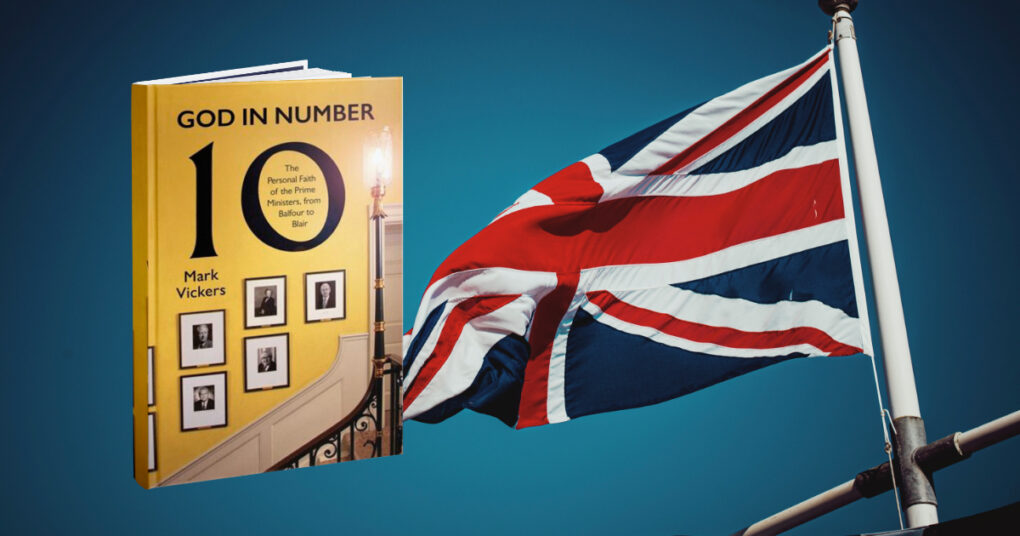

God in Number 10: The Personal Faith of the Prime Ministers, from Balfour to Blair

Mark Vickers

SPCK Publishing

481 pages

ISBN 9780281087280

The faith, or lack of it, of the Prime Ministers of the United Kingdom has been an area that has suffered from widespread neglect by historians. Mark Vickers rectifies this omission in his well-researched and richly detailed volume which casts a very personal light upon the inhabitants of one of the most famous residences in the United Kingdom: Number 10 Downing Street.

The author, Mark Vickers, read history at Durham University and practised law in London before studying for the priesthood at the English College, Rome. He was ordained for the Diocese of Westminster in 2003 and is currently a parish priest in West London. God in Number 10 is his fourth published title.

The book follows a basic chronological order, starting with Arthur Balfour (PM from 1902 to 1905) and ending with Tony Blair (PM from 1997 to 2007), attributing a chapter to each PM. These do not comprise standard mini biographies, but you do learn a great deal about the personal lives of each of the Prime Ministers – details which often doesn’t reach the public sphere. More so, you get a taste of the political landscape of the UK throughout the 20th century, as well as the changing role that Christianity played in British life over the course of that century, the relationship between Church and State and the reasons for the declining influence of faith based perspectives in public discourse.

At the beginning of the 20th Century, British society was in the midst of spiritual turmoil. The educated classes were suffering from a spiritual crisis as a result of modern biblical criticism and recent scientific discovers. Charles Darwin’s, On the Origin of Species, coupled with the horrors of war had prompted much doubt in the existence of an all-powerful and loving God and the credibility of the Bible had been greatly damaged. The corridors of Cambridge and Oxford were very much hostile to the voice of faith. Yet, in spite of all this, Stanley Baldwin (PM 1923-1924, 1924-1929 and 1935-1937), a mystic of sorts, still believed himself to be ‘God’s instrument for the work of the healing of the nation.’

In the early part of the century, Ramsay MacDonald (PM 1924 and 1929-1935) dabbled in palmistry and horoscopes. The mother of Anthony Eden (PM from 1955 to 1957) used a medium to speak to his brother, Jack, who was killed in the trenches during WWI. Arthur Balfour, who struggled to accept the Christian teaching on the afterlife, regarded talking to ghosts as a more rational alternative. As Vickers writes, the spirits he met were ‘not politically neutral’ as they informed him that ‘the return of a Conservative government under Balfour was essential to save the Crown from revolution.’

As Britons became richer, swapping the hardships of wartime rationing for package holidays and indoor toilets, Alec Douglas-Hume (PM from 1963-1964) hosted Billy Graham and Cliff Richard and warned that prosperity was no substitute for ‘service and sacrifice.’ He regarded faith as the ‘basic if subconscious influence in the life of the British people,’ which he demonstrated through his loyalty to Christian teaching.

Labour leaders, on the other hand, sought to translate piety into social action. Clement Attlee (PM from 1945 to 1951) believed in the ‘ethics of Christianity,’ but not the rest of ‘the mumbo jumbo.’ I wonder what he thought of his wife’s dabbling in clairvoyance? For an atheist, Attlee took a surprising interest in ecclesiastical affairs, being of the view that the Church of England needed a serious overhaul. Many politicians despaired of the Church’s obsession with personal morality and feared it was out of touch. Yet, much of the Left retained a streak of nonconformist puritanism. One of the very few things Harold Wilson (PM from 1964 to 1970 and 1974 to 1976) is praised for today is the liberalisation of abortion and homosexuality, but Vickers speculates that he found both distasteful. Perhaps he was sensitive to the views of his Huyton constituency, which contained many Catholics? By contrast, when James Callaghan (PM from 1976 to 1979), was seeking to represent Cardiff South, he had to reassure the locals that his name might be Irish but he had been raised a Baptist.

Of all the Prime Ministers of the 20th Century, two names are remembered (for better or worse) above all others: Winston Churchill (PM from 1940 to 1945 and 1951 to 1955) and Margaret Thatcher (PM from 1979 to 1990). Their religious convictions will be of particular interests to readers. Churchill appears to have held ever shifting beliefs about the existence of God, the nature of the afterlife, and the genuineness of Scripture. For some time, he had a personal astrologer, who advised him on government policy relating to industrial disputes and diplomatic crises. Yet, when the free world was facing the horrors of the Nazi war machine, Churchill repeatedly invoked God’s blessing upon the Allied cause. When Churchill met with David Ben-Gurion, the first Prime Minister of Israel, the two men debated who was the greater: Moses or Christ? Ben-Gurion said Jesus. Churchill favoured Moses.

Margaret Thatcher was raised as a Methodist and even preached as such during her years at Oxford, before later becoming a member of the Church of England. Her Christian faith was personally important and, more significantly, it moulded her political policies and decisions. However, as Prime Minister, she repeatedly found herself in conflict with the Churches, not least in regard to her ‘Sermon on the Mound’ address to the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland in 1988, where she shared some controversial thoughts on her religious and political thinking. Thatcher blamed some of the loss in Christian zeal on the Church of England becoming more political, than religious. She didn’t hold back in reprimanding a ‘socialist CND-promoting vicar’ that his views were the cause of his ‘lack of a congregation.’

The book contains many episodes of anti-Catholic prejudice. Vickers writes that Catholicism was viewed ‘as restrictive of intellectual freedom and scientific inquiry.’ Henry Campbell-Bannerman (PM from 1905 to 1908) regarded the Papal Mass as merely ‘uncommonly fine’ and Pope Pius IX was ‘a kindly pleasant looking old gentlemen’- quite an endearing remark from a spiritual son of John Knox! However, there was no danger of conversion to Catholicism as Campbell-Bannerman discovered not ‘the smallest particle of devotion’ among the congregation at the Pontifical High Mass and regarded the sight of pilgrims ascending the Scala Santa on their knees as ‘degrading.’ Anthony Eden appears to have loathed Rome and Harold Macmillan’s (PM from 1957 to 1963) mingling with Anglo-Catholicism nearly sent his mother to an early grave. Over time, sectarianism disappeared. James Callaghan, who never personally harboured hostility to Catholics, came closer to the Church when his wife was cared for in a home run by nuns. Tony Blair converted to Rome under the influence of someone more indomitable than the Holy Spirit: his wife, Cherie Booth. ‘This all began with my wife,’ he explained.

Vickers concludes that PMs overwhelmingly ‘derived their sense of identity from party politics’ not from Church-allegiance, and even though he ranks Blair as perhaps the most religious Prime Minister, it’s striking that when Pope John Paul II personally advised him against the Iraq War, Blair ignored him. Protestants long warned that a Catholic PM would take his orders from the Pope. On the one occasion when this might have been for the greater good, it sadly did not materialise.

The concluding chapter is of particular note as it draws attention to an unusual trend. For one of the most striking features of God in Number 10 is that as the Christian faith declined in influence in society as the century progressed, particularly from 1960 onwards, Britain’s Prime Ministers became more believing. Of the final eight PMs of the 20th Century, only Callaghan professed not to be a believing Christian. In comparison to the first period of the 20th Century, Vickers suggests that only Baldwin was an ‘uncomplicated orthodox Christian.’

In 2003, Tony Blair was asked during an interview about his faith and the extent to which it bonded him to President George W. Bush. At that point, Alastair Campbell, famously interrupted and declared ‘we don’t do God.’ Recent research from the think-tank Theos, found that people are increasingly suspicious of those with religious views holding high office, especially those they consider to be ‘old fashioned’ from a moral perspective. The relationship between religion and political discourse remains ‘complicated.’ However, with God in Number 10, Mark Vickers has produced a magnus opus which shows the extent to which Prime Ministers ‘have done God’ and how the Christian faith shaped political thinking during the 20th Century.