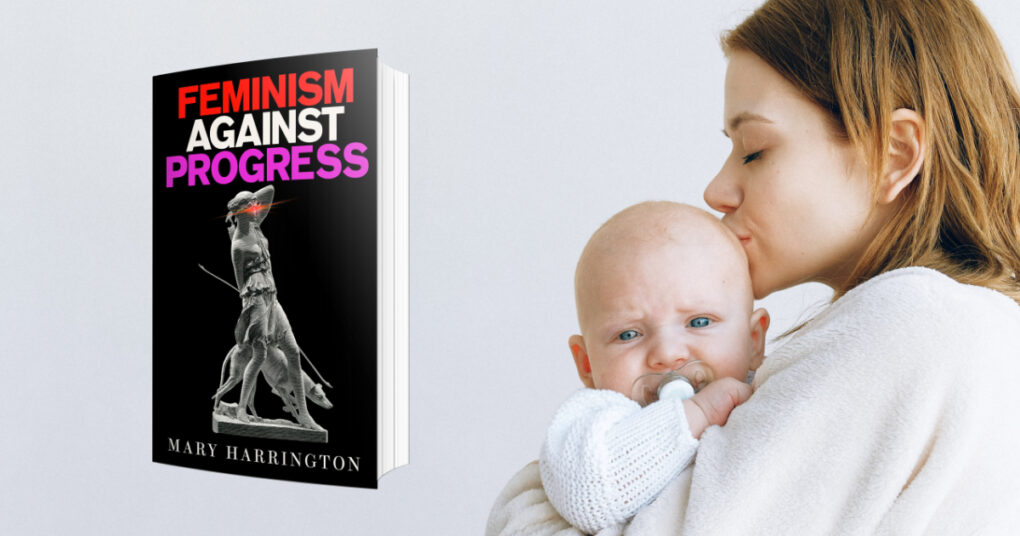

Feminism Against Progress

Mary Harrington

Forum-Swift Press

2023

224 pages

ISBN 978-1684514878

Anyone familiar with Mary Harrington’s columns in unherd.com will know her as a thinker of exceptional originality, acuity and freshness. Her first book does not disappoint her fans. In fact it is an eye popping analysis of what she calls “reality denying”, woke feminism as it has evolved since the 1960s. She describes herself as a “revisionist feminist” because she believes the stances of modern day, self-declared feminists are fundamentally inimical to the welfare and interests of most women and that people like herself have a better right to describe themselves as feminists.

Mary Harrington has come full circle from buying into and living the most extreme expressions of the feminist liberation creed. She was, as she acknowledges, woke and radically so before the term was coined. She experimented with “drugs, kink and non-monogamous relationships” in her twenties. She was committed to living in complete freedom and rejected all hierarchies. Her experience of living with the equally radically minded showed her that power dynamics are part of all human interactions and not, as she believed, the preserve of capitalism and patriarchy. That seems to have been her first reality check.

Harrington dates the degeneration of culture to the early sixties when the “first transhumanist technology” revolutionised the lives of both women and men. That “transhumanist technology” was of course the contraceptive pill. It disrupted women’s natural biorhythms and suppressed their fertility, the core and defining quality of femaleness. It was the first wave of what Harrington calls the cyborg revolution which gave women and later men the power to overwrite nature. The pill paved the way, in terms of both biotechnology and ideology, for the developments that now underpin transgenderism and reproductive technologies. Essentially, it all comes down to understanding human biology as something to be controlled and manipulated, something we define rather than something that defines us. The hormonal suppression of female fertility is on a continuum with transgender hormonal treatments. In both cases, the impact on both the mind and the body as a whole goes far beyond the immediate aims of the treatment. This is acknowledged and sometimes desired in the case of transgenderism but tends to be played down in relation to hormonal treatment

intended solely for contraceptive purposes. Harrington also maps the direct and inevitable link between the contraceptive pill and abortion. This suggests a similar parallel between transgender hormone treatments and surgical gender realignment. In both cases, nature suppressing chemicals need the backup and support of non-therapeutic, mutilating surgical procedures.

From the standard feminist perspective, it is about flattening the differences between the sexes and giving women the same degree of control over their reproductive capacity as men. Feminists, who are generally middle class professionals, support transgenderism because it affirms the idea that there is no fundamental, non-malleable difference between the sexes. Each can become the other with a cocktail of medical and surgical interventions. She uses the image of lego figures that can be taken apart and put back together according to personal choice.

None of this is progress in any positive sense for Harrington. The commodification and monetisation of the human body and sexuality has been disastrous for both sexes but particularly women, apart from arguably a small elite. It is, she says, “the extreme end of capitalisation”, the capitalisation of the human body. Poor women are exploited for prostitution, sanitised as “sex work”, and surrogacy to support the new freedoms of those with the power to purchase them. It is ironic, given that radical feminism leans politically left, that biotechnology, as Harrington points out, fuels a multi-billion industry where ethical, and perhaps medical considerations too, are sidelined as peoples’ insecurities and hubris are exploited without scruple.

Harrington’s book offers an interesting overview of social development through the ages. Up to the Industrial Revolution, work was shared by both sexes. The work of the woman, preparing food, weaving, spinning and other agrarian and artisanal craftwork combined well with the care of small children who would share the work once they were old enough. When work, including the textile industry, heretofore a domestic pursuit, became mechanised in factories, feminism emerged as a two way movement. What Harrington calls, “the feminism of freedom”, the kind that won out in the end, sought to secure an equal place in the world of work for women and promote their rights in the new order with its economic asymmetries. The second form of feminism was “the feminism of care” which placed a value on work outside the market. This produced the cult of domesticity that prevailed, more or less, until the legalisation of contraception in the early sixties.

It is, Mary Harrington concludes, the “feminism of care” that is needed today to promote in particular the welfare of the vast majority of women for whom the “feminism of freedom” has proved a dystopia. She gives careful and nuanced thought to how our society can re-set the lost balance and harmony in the relationships between men and women, women and children and fathers and their children. She maps three paths towards the restoration of a healthier society.

These paths are straight out of Christian, and in a specific way Catholic, teaching though Mary Harrington, unlike many other agnostic or atheist writers, like Jordan Peterson and Douglas Murray, does not join the dots quite so explicitly. She advocates, in the first place, supporting and promoting marriage. Harrington concludes that marriage, properly understood, is the most secure social unit humankind has ever known. We need to recover an understanding of marriage that goes beyond romance and is centred on an understanding of commitment and care within an indissoluble union that is “a covenant rather than a contract”.

The second path to undoing the harm of our current anthropological experimentation is to concede that the sexes develop differently and have separate needs. To this end, she advocates the validation of “men only” spaces where younger men are socialised because traditionally “men civilise men first”. This links up with the findings of other

conservative commentators that the lack of a father in a boy’s life produces feral teens. She also notes that denying such space to males undermines the case for separate spaces for women. She points out that young men, especially working class and divorced young men, are the loneliest people in the world today with the highest risk of psychic distress and suicide. Loss of a female partner can cut them abruptly from their social outlets. The traditional “men only” spaces, like mens’ clubs, which are edging back in the shape of men’s sheds, traditionally offered friendly, intimidating places for unattached men of all ages, places of male to male mentoring and solidarity.

The third way to societal recovery Harrington proposes is what she terms “rewilding sex”. Non contracepted sex means “less real opportunities for bad sex”, a “robust reason to say no” and a greater imperative to choose carefully “who you sleep with”. It means less pressure on young women to engage in casual sex. In marriage, she says, “sex recovers the seriousness it is meant to have”. She says the “intensity, beauty and mystery of sex” cannot be realised in transient relationships when a woman’s fertility is suppressed and she is suffering the mind, mood and body altering effects of hormonal drugs. The inbuilt “risk” or possibility of procreation is an inherent part of the “intensity, beauty and mystery” of sex for Harrington.

This book is charged with the zeal of a writer whose research is grounded most of all in the lived experience of a feminist dystopia, its pain, hollowness and disillusion. Her awakening to the truth of her nature as a woman came through marriage and motherhood in her thirties. Motherhood was deeply transformative for her and rendered irrelevant the values of “freedom and autonomy” her feminism had instilled in her as fundamental to any notion of self worth. One wonders, however, if her new found convictions can be sufficiently supported by self-belief alone without some buy-in to the faith culture that developed and promoted them and without which ultimately their rationale lacks a secure foundation?

Harrington touches base with the foundations of Christian thought on marriage with penetrating insight and a forthrightness that would be hard to find in many a pastor up against the headwinds of the current zeitgeist. Writing of mediaeval women as portrayed by Geoffrey Chaucer in his Canterbury Tales, she says “the world (was understood) as a set of nested hierarchies in which God governed mankind as the king governed his subjects and a paterfamilias governed his household. Within that world view, Christian teaching held that higher rank implied not simply a relation of domination and control, but one of service and sacrifice.” She says “this idea of mutual love coexisting with hierarchy is alien to a modern perspective in which all such asymmetries are treated as exploitative by definition.”

Mary Harrington is a compelling writer and speaker; reading and listening to her is time very well spent indeed. For Catholics, she joins a growing list of allies who find their way to the truths of religious tradition via the “steep and thorny path” of testing emerging orthodoxies to destruction. Feminism Against Progress is essential reading for all who battle at any level with the hard dogmas of today’s secular liberals. I cannot

recommend it highly enough.