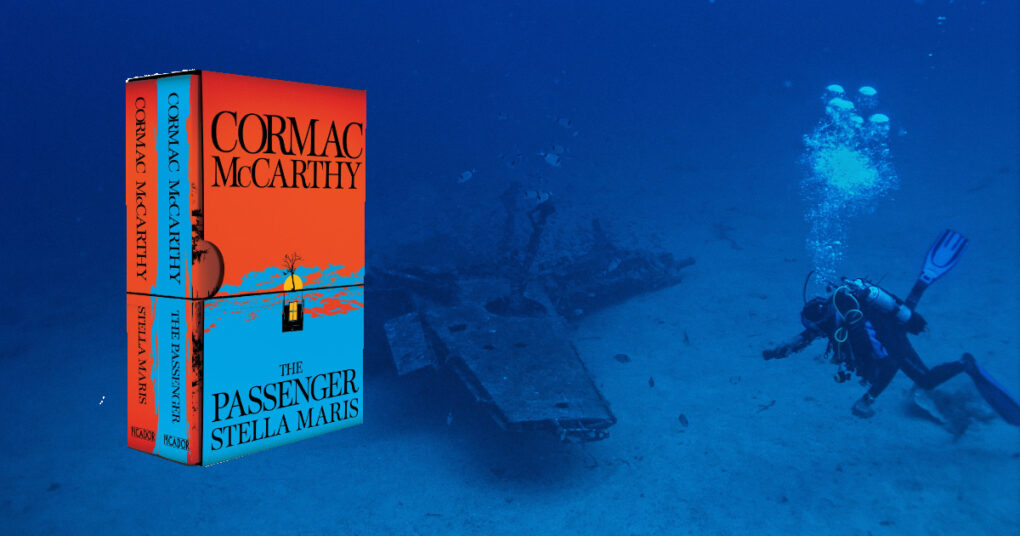

The Passenger

Comrac McCarthy

Knopf Publishers

2022

383 pages

ISBN 9780307268990

Stella Maris

Comrac McCarthy

Knopf Publishers

2022

208 pages

ISBN 9780307269003

Before October, Cormac McCarthy’s legion of fans had been waiting sixteen years since the publication of his last book, The Road. As McCarthy approached his tenth decade, many had given up hope that the promised books would materialise. Thankfully, in October, The Passenger was finally published, soon followed by its companion novel, Stella Maris.

The books are not alike. The Passenger is centred around Bobby Western, a salvage diver in Louisiana who investigates a submerged aeroplane and discovers that one passenger who had been on board is not accounted for among the victims. The mystery of the eponymous passenger sets off a chain of events where Western, still mourning his sister’s suicide years earlier, comes to the attention of unknown and sinister forces.

In what first appears to be the beginning of a classic McCarthyesque battle for survival, Bobby tries to evade his pursuers while still appearing more interested in learning about his deceased sister than in finding out why he has become the quarry of a hidden pursuer.

Stella Maris is set almost a decade earlier in the psychiatric facility where the brilliant and troubled Alicia Western is being treated. It is written in the form of dialogue between the beautiful 20-year-old mathematician and her psychiatrist. Like Bobby, Alicia has fled her previous life grief-stricken. Her brother has been in a car accident and is now in a coma. Rather than give her consent to switch off the life support machine, she has returned to the mental institution where she was previously treated.

Their family’s backstory is gradually revealed, particularly the details of their late father’s role in the Manhattan Project. Both are haunted by the implications of this, especially Alicia, whose mental illness manifests itself with hallucinations involving characters led by a limbless deformed creature, The Thalidomide Kid. “I have clandestine conversations with supposedly nonexistent personages,” as she puts it. The inclusion of a female protagonist represents a new departure for McCarthy, who said in 2009 that he had long planned on writing about a woman but that he would “never be competent enough to do so.”

Both books feel different to most of his other work, Stella Maris in particular, and some readers may be surprised at the lack of violence. McCarthy’s magnum opus is Blood Meridian, a tale about psychotic nineteenth century scalp hunters preying on the weak, and the No Country for Old Men novel and the outstanding film adaptation by the Coen brothers cemented his reputation as a writer with an extraordinary capacity to depict true evil. Man’s frequent inhumanity was but one commonly occurring theme in a literary career that stretches back to the mid-1960s, and he still has the ability to startle readers with his descriptive prose.

After a disturbed Bobby has surveyed the contents of the crashed plane, an experienced old hand describes a previous episode involving the removal of victims of another air accident: “They keep wantin to put their arms around you… They were all swollen in their clothes and you had to cut them out of their seatbelts. Quick as you did they’d start to rise up with their arms out. Sort of like circus balloons.”

Both Bobby and Alicia experience the profound social isolation which is so commonly felt by McCarthy’s characters. “They ain’t a soul in this world but what is a stranger to me,” laments the grieving mother in one of McCarthy’s earliest books, Outer Dark.

The Border Trilogy books that earned McCarthy global fame in the 1990s after decades of relative obscurity feature characters venturing alone through the lawless borderlands between America and Mexico, as does Blood Meridian, while The Road depicts a mostly deserted, apocalyptic America in which a father and son do everything they can to avoid being detected by other survivors.

Bobby and Alicia’s aloneness is of an altogether different variety, stemming from the deep unconsummated love affair which exists “[i]n spite of the laws of Heaven.” Incest too is a recurring feature of McCarthy’s work, though never to the extent it is explored here. Years after Alicia’s death, the lawyer who aids Bobby knows with immediate certainty that the deceased prodigy must have been a great beauty, for “beauty has power to call forth a grief that is beyond the reach of other tragedies.” Neither Western sibling can cope without the other, and the flight of each comes in the wake of the other’s apparent loss.

There is another way in which the combined story is classic McCarthy. Even at his darkest – especially at his darkest – questions of religious faith pervade much of his work, which has rightly been described as God-haunted. Born to a brilliant Jewish scientist who caused their Catholic mother to doubt her faith, both Alicia and Bobby ponder ceaselessly the purpose of their lives. There is a clear nihilistic strain within Alicia’s psychological make-up, and her views are similar to those expressed by the atheist professor in The Sunset Limited the 2006 play (and 2011 film) which is McCarthy’s deepest examination of religious belief and human existence.

When asked by her doctor what she would change if she could change anything, Alicia responds that she would “elect not to be here. In this consultation. On this planet.” Like the mother in The Road, her only hope is for “eternal nothingness;” not only does she not want to be, she wishes “never to have been.”

The former altar boy is too serious a moral thinker to leave it at that. Hiding in faraway exile, Bobby hears the cautionary words of an unbeliever who could not adequately respond to the warning that a “Godless life would not prepare one for a Godless death.” There is no final resolution in the books, and after a promising start, The Passenger wanes in narrative terms as the echoes of the great pursuit in No Country for Old Men grow more faint.

Ultimately, both books are about Alicia. She is undoubtedly an intriguing character, especially the enchanting and distant being depicted in the short snapshots contained in The Passenger. But McCarthy’s female protagonist is completely unrelatable: a socially detached mathematical genius who claims to have read 10,000 books and remembered everything in them.

No living writer can match the great American’s prose. But even at the height of his powers, such as the frightening philosophical monologues of the murderous giant Judge Holden, his writing sometimes tended to be overwrought at times. The problem is more obvious here, particularly when it comes to Alicia. As noted by Park MacDougald in his Unherd review, some of Alicia’s dialogue strongly resembles a 2017 non-fiction essay on the origin of language.

Likewise, the mental patient’s criticisms of the moral shortcomings of the philosopher Martin Heidegger closely resemble what McCarthy expressed in a recently broadcast interview, also recorded five years ago. The sloppiness can readily be forgiven. Cormac McCarthy will be ninety next summer, and a newly released video of the reclusive writer shows he has aged significantly in the last five years.

As he has declined physically, so too has his writing. These companion novels are not failures, but they do not come close to reaching the dizzying heights of his greatest works, and it would be unreasonable to have expected that they ever would. “What could I ask of you that you’ve not already given?” utters the Judge in Blood Meridian, perhaps the most captivating villain in literature. Grateful McCarthy fans reflecting on his career could say the same today.