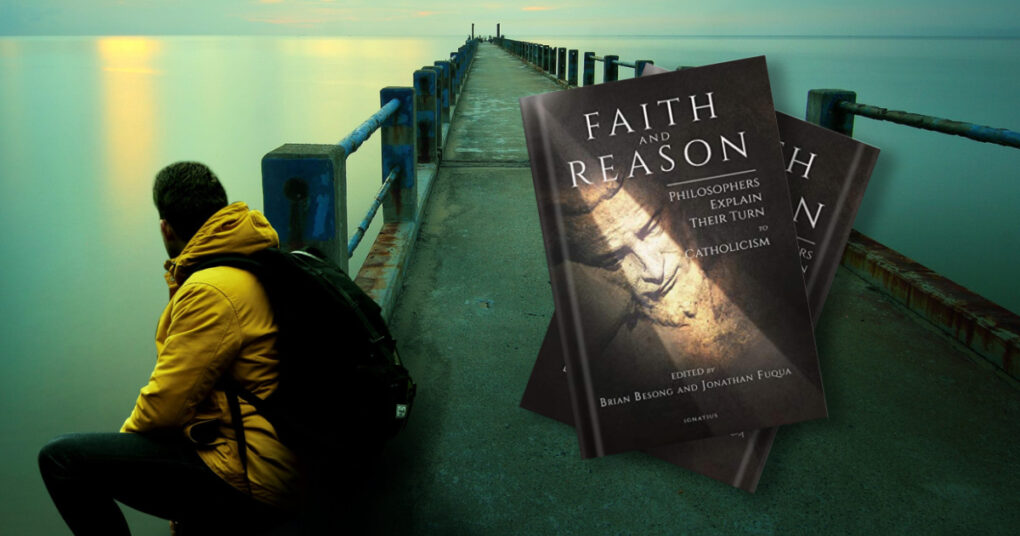

Faith and Reason: Philosophers Explain Their Return to Catholicism

Brian Besong and Jonathan Fuqua (eds.)

Ignatius Press, San Francisco: 2019)

2019

289 pages

ISBN: 9781621642015

Faith and Reason consists of ten chapters, written by ten different philosophers, plus an Introduction by the editors and a foreword by Francis Beckwith, Professor of Philosophy at Baylor University. Each chapter is an account by the author of his or her conversion (or reversion, in the case of Edward Feser) to the Catholic Church. As indicated, all of the authors are professional philosophers very active in their field, and therefore, one might be led to expect a certain sameness in the chapters. However, they are strikingly distinct: there are many paths to Rome, it would appear, and it is a city with many gates. Each chapter richly repays careful reading, and issues of interest to any and all Catholics emerge in all of them. Clearly, some will be more or less engaging to certain readers, depending on the background and circumstances of the individual reader, but none are negligible.

Certain factors do emerge as common characteristics, of course: every chapter is tightly argued, and reasoned argument is clearly a factor in all of these stories. Almost all of the authors come from Protestant backgrounds, predominantly (although not exclusively) Baptist and Lutheran, and in some of the chapters (Koons, Gage, Kreeft and Judisch), reasoned argument is used more in examination of the claims of the differing strands of the Reformed tradition rather than in exploration of any philosophical school of thought. Others, notably Feser, Budziszewski and Cutter, demonstrate how an extended engagement with certain schools of philosophy actually led them to Christianity more generally, to begin with (C. S. Lewis’s “mere Christianity”), and eventually to the Catholic Church. The final chapter, “A Spiritual Autobiography” by Candace Vogler tells a different story again: Prof. Vogler suffered the most appalling abuse at the hands of her father from a very early age (she does not go into details, but the hints are sufficient) and subsequently had to cope with a very dysfunctional family, and the story of how she worked through all of this with the help of her studies in Philosophy makes for compelling reading. In many ways, this is the least technical of all the chapters, and may well have the widest appeal.

All of the individual chapters are extremely well written, which in itself is a testimony to the value of philosophy as an aid to clarifying one’s ideas. Some are quite technical, especially those of Budziszewski and Cutter, which may make them something of a challenge to non-philosopher readers: the technicality in Busziszewski’s case consists of a stringent examination of the claims of “science” – not real science, but the materialist goddess erected by contemporary culture and media. In order to make that distinction clear, Budziszewski has to delve into some actual physics, and pose the question as to why this should work against religious belief: in fact, of course, there is nothing inherently contrary to the possibility of religious belief in actual scientific work. This is a point that has been made repeatedly, of course, in various ways: the quasi-religious dimension of certain contemporary scientific theories such as the Big Bang has been pointed out; the active religious belief of notable scientists such as the cosmologist Georges Lemaitre and the geneticist Jerome Lejeune, which in no way contradicted their scientific work, has been highlighted, and yet an awful lot of people remain convinced that science and religion are opposed. Budziszewski brings out an aspect of the debate which may do a lot to explain this, and that is the commitment of certain scientists to philosophical materialism as an assumption from which they begin rather than as a conclusion that they have eventually reached. The popular assumption is that scientists begin with a blank slate, and eventually come to the conclusion that materialism or naturalism or physicalism (the belief that there is nothing at all in existence beyond material entities) is true. In fact, there is no blank slate, as the well-chosen quotation from Lewontin (Harvard scientist) makes abundantly clear: Lewontin defiantly declares that he would remain a materialist even if the evidence pointed in the opposite direction. This conviction on the part of some, but by no means all, scientists, amplified to an enormous extent by prestigious organs of the media, does much to explain the ongoing popular conviction that religious belief is something one holds in the teeth of scientific evidence to the contrary. There is no scientific evidence for the non-existence of God. There couldn’t be: you cannot prove a negative.

Physicalism, or materialism, emerges again in Cutter’s article. However, here we are concerned with Anglo-American analytic philosophy. Cutter hones in on philosophical anthropology as his particular field of concern, and the phenomenon of human consciousness in particular, and notes that the attempt to explain certain human phenomena (classically believed to be the fruit of human reason) in materialist terms ultimately fails. Materialist philosophical anthropology set out to demonstrate that such things as free will, the capacity for reflection and so on were simply epiphenomena (i.e., highly developed instances) of material processes, and that consequently, there was no reason to believe in any kind of spiritual dimension to human existence, nor would the hypothesis of God make any sense. Cutter demonstrates that these kinds of arguments simply do not stand up to scrutiny: an intense examination of the human capacity for cognitive development and a consideration of the horrible moral implications of a materialist anthropology lead him to conclude that it is simply impossible. At that point, he notes, and taking several other elements into consideration, he “began to find Christianity plausible”. This is a difficult chapter because he packs a great deal into a few pages – the reader has to go very slowly in order to keep up – but it is extremely clear and well written.

Feser begins from the perspective of the teacher of philosophy: having convinced himself, as he thought, of the validity of Nietzsche’s claims, he obtained a job teaching Philosophy of Religion to undergraduates, and in the effort to make the classes more interesting, ended up arguing himself back into the Catholic Church. Feser is known for his work on the arguments for the existence of God, and his account of how he went from teaching a dull, anthologised, ultimately falsified version of these to engaging with them more seriously until eventually he realised that he had to accept them if he was to remain a philosopher at all is very engaging. Philosophy of Religion is very often taught as a means of assuring students that religion is every bit as stupid as the general culture tells them it is, so Feser’s account of his increasing interest and conviction of the merit of classical theistic arguments is very refreshing. He also generously gives the names of several books which he himself found helpful in his research, which is useful to the reader wanting to know more.

As mentioned, every article highlights something of concern to contemporary Catholics. In his discussion of his move to Catholicism, the noted contemporary apologist Peter Kreeft engages with literary sources in an entertaining way, and gives a list of classic Catholic works in an extensive footnote. Logan Paul Gage takes up the question of the Canon of Scripture: why do Catholics and Protestants have different Bibles? What is the explanation of the Protestant rejection of the Deutero-Canonical books of the Old Testament, and is it justified? Cradle Catholics, who tend to feel inferior to Protestants in Scriptural matters will be pleasantly surprised by this discussion of Scriptural matters, in which Gage sees the Catholic Canon of Scripture as valid. Robert C. Koons takes up the question of justification by faith, a most important element in Luther’s rejection of Catholicism, and provides an ample discussion of the 1999 Lutheran-Catholic Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification, and on the debate that followed. The joint article by Lindsay K. Cleveland and W. Scott Cleveland treads the path mapped out by Scott and Kimberly Hahn in Rome Sweet Home: each recounts his/her story of conversion, weaving it into the story of their married life and careers. How a serious engagement with religious faith affects the lives and family lives of those who engage in it is a key theme here, and this will be of compelling interest to several readers.

Certain key themes run through all the articles: reason obviously, and, in most cases, an engagement with the thought of St Thomas Aquinas eventually. This is interesting, because none of these people start out from a perspective where Aeterni Patris (Leo XIII’s encyclical recommending the study of St Thomas to all Catholics) would have been a reason to pick up Aquinas, and yet they do. All authors note the hostility of contemporary culture to religion in general and Catholicism in particular, and all recount how they managed to escape from that. In the Introduction, the Editors note the particular manifestation of this hostility in professional Departments of Philosophy in particular, but in fact it runs through everything, literature, history and the sciences as much as through philosophy. The difference lies between those subjects which have enough internal coherence and integrity to allow for a dispute with this, and those areas where perhaps the idea that there is a discussion to be had is definitively buried.

In conclusion, this book is a wonderful read for anyone interested in the issues of religion, philosophy, science and intellectual activity generally. It is demanding – the authors are really determined to give value for money but, unlike many contemporary books which are equally demanding because they are deliberately obscurantist, this will repay the patience and effort it will take to read it. Philosophers may have an easier time in some respects, but this is not merely a book for professional philosophers. There is something here for everyone.