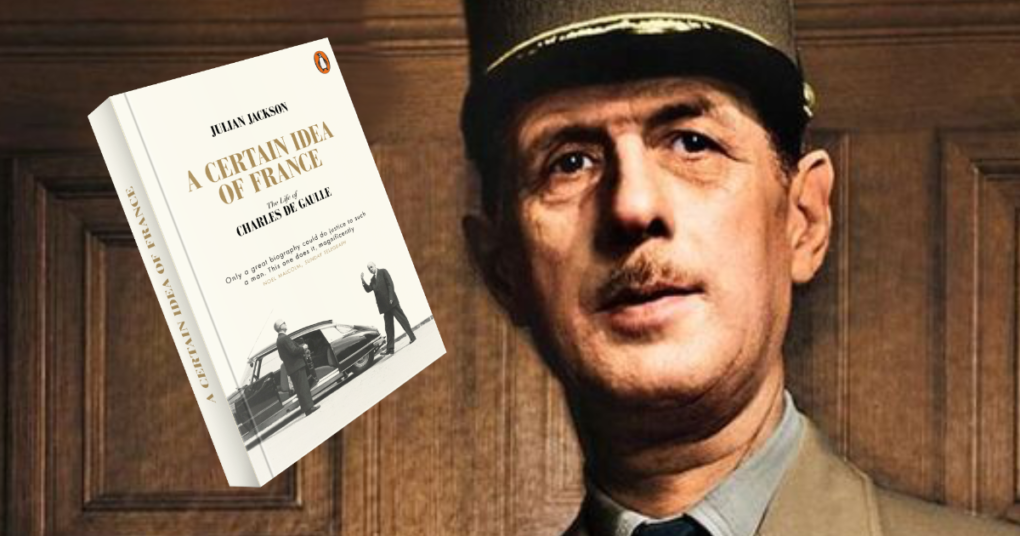

A Certain Idea of France: The Life of Charles de Gaulle

Julian Jackson

Penguin

2019

944 pages

The greatest leaders demand the greatest attention from any would-be biographer.

Charles de Gaulle belongs to the highest echelons of history’s statesmen. For writing the acclaimed biography A Certain Idea of France published in 2019, Julian Jackson deserves recognition in the highest echelons of historians, in the company of Robert Caro, Andrew Roberts and few others.

His subject’s life spanned eighty years, which encapsulated heroic service in the First World War, intense historic study and extraordinary prescience in the decades following it, a rise to the position of national saviour in the wake of France’s collapse in 1940, the country’s liberation from the Nazis, de Gaulle’s self-imposed exile and triumphant return, not to mention the creation of the Fifth (and still enduring) French Republic.

De Gaulle opened his memoirs by writing that he had “always had a certain idea of France,” and over the course of 944 pages, Jackson brilliantly describes what this idea was, and how the deeply conservative de Gaulle managed to steer the nation through periods of rapid change, while still holding to this vision.

Jackson’s book contributes enormously to our understanding of a captivating figure. One of the many accomplishments is building on the work of earlier writers by demolishing the view that the General’s Catholicism was incidental to his character and actions.

A throwaway remark by de Gaulle that he was “Catholic by history and geography,” coupled with a tendency to appear distracted during Mass, has occasionally been taken to imply that de Gaulle’s Catholicism was merely cultural.

Jackson tears this viewpoint apart. Of his family background, there can be no doubt. As a teenager, de Gaulle served as a stretcher bearer in Lourdes, and after the Great War, the entire de Gaulle family returned together in pilgrimage to honour a promise Madame de Gaulle had made if all four of her sons were to survive the conflict.

Both of Charles’s parents were devout. In one illuminating anecdote, the scholarly monarchist Henri de Gaulle chastised his officer son for praising the skills of a general of the French Revolution.

One of the many secrets of de Gaulle’s extraordinary rise lay in his cultivation of a broader sense of French patriotism which could include those who did not share his family’s religion and monarchism, but there can be no doubting de Gaulle’s lifelong commitments to those beliefs. Again and again, Jackson shows this side of him to the reader.

Writing to the philosopher Jacques Maritain about how some Catholics had embraced the Vichy regime, de Gaulle acknowledged that “the bishops have behaved badly, but there are good curés, simple priests, who are saving us.”

In the 1960s, like many French conservatives, de Gaulle expressed suspicion about the reforms underway in the Church. “There are always people who want to go so fast that they destroy everything. I’m not sure that the Church was right to suppress processions and the Latin service. It is always wrong to give the impression of denying oneself and being ashamed of what one is. How can you expect others to believe in you when you do not believe in yourself?” he asked.

The clearest example of de Gaulle’s piety was not shown in words however, but in how he responded to the birth of his daughter Anne, who had Down Syndrome. At the time when societal prejudice led most families to place such children in institutions, the de Gaulles would not hear of this, in spite of the severity of her condition which meant she could not speak, and only learned to walk at the age of 10.

Instead, the taciturn military man developed a uniquely strong relationship with his youngest child, walking slowly hand in hand with her in the botanical garden after finishing work and spending hours speaking to her.

As is always the case, greatness and goodness went hand in hand. It was as if a man who maintained a distance from all around him knew instinctively that he must be forever close to the daughter who needed him most, “the one person who perhaps was not in awe of him,” as Jackson observes.

De Gaulle’s words to a military chaplain in 1940 gave an insight into what Anne meant to this normally icy titan: “Her birth was a trial for my wife, and for myself, but believe me, Anne is my joy and my strength. She is the grace of God in my life. She has kept me in the security of obedience to the sovereign will of God.”

When Anne died at the age of 20, the curé found de Gaulle collapsed in grief. “From Heaven, let little Anne protect us,” de Gaulle wrote, in a letter to his surviving daughter.

Religion bound de Gaulle to his family’s past and that of his nation. On his last day, November 9th 1970, de Gaulle wrote to thank a friend for sending him a genealogy of his family tree, and noted the two strands of their identity which were of greatest importance, writing that “[i]t is pleasing to see in all of them, dead and alive, such depths of courage and fidelity to religion and to the fatherland.”

For de Gaulle, the connection between France and Catholicism was obvious. He often spoke of his nation’s 1,500 years of history, beginning with the baptism of Clovis.

During the First World War, he expressed dismay at the Pope’s neutrality in a conflict which pitted his country against the Ottoman Turks, adding that “the destruction of the Turkish empire would be a terrible blow to Islam. The repercussions would be immense, above all in Africa, where the doctrine of Muhammad is spreading with frightening rapidity, preventing the success of our missionaries, and also, the progress of our civilisation.”

In the traditional divide between France of Joan of Arc and France of the Revolution, between Right and Left, there was no doubt where his allegiances lay. Pouring scorn on the tendency of French socialists to valorise revolutionary values, pointing instead to “the intellectual and spiritual prestige of France in the 17th and 18th centuries.”

None of these statements were unusual for a French conservative or a French king. What set de Gaulle apart from the monarchs was his ability to hold together a diverse nation, and his possession of greater wisdom in understanding the limits of his own power.

As a high-ranking officer desperate to change France’s military approach before the disaster of 1940, he worked with left-wing politicians to seek to raise the alarm about the need for a professional army including armoured units.

When invoking historic examples to inspire the French public, he looked to a diverse array of French heroes like the secularist Clemenceau. And unlike other French Catholic leaders, he harboured no anti-Semitism, and instead attracted many Jewish followers.

This did not mean his religious faith failed to influence his political actions. Indeed, Jackson described how de Gaulle’s belief in Catholic social teaching stirred him to pursue the idea of “association” between employers and workers: another source of an extraordinary popularity which cut across France’s classes.

Shared faith helped him to form a strong personal relationship with the West German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer, which in turn allowed for the creation of a warm Franco-German relationship upon which European unity would be built.

Unlike the Bourbon monarchs whose example he deeply respected, de Gaulle knew where religious and political policy diverged, but his convictions about the roots of French national identity allowed him to understand problems which subsequent French leaders have refused to face.

During the Algerian War, while other French nationalists believed France could integrate the country and its people in order to prevent Algerian independence, de Gaulle did not – mainly because his French patriotism was not rooted in the liberal and secular universalism of 1789.

“Try and integrate oil and vinegar,” he told a Gaullist politician in 1959. “Shake the bottle. After a moment they separate again. The Arabs are Arabs, the French are French. Do you think the French can absorb 10 million Muslims who will tomorrow be 20 million, and after tomorrow, 40?…. My village would no longer be called Colombey-les-Deux-Églises but Colombey [of] the Two Mosques.”

Much of the last several decades of French history has involved the playing out of an experiment which de Gaulle predicted would fail. With each passing presidency, the giant’s stature grows in comparison with the pygmies who have succeeded him in the Élysée Palace, and led their nation down the path of decline.

Regardless of his country’s current malaise, de Gaulle’s achievements in saving his country’s honour in its darkest hour, and giving it an enduring political system, can never be taken away.

Julian Jackson has given the world an extraordinary biography of a man whose idea of France was both certain and correct.

This book tells us so much about France and its unique history and character. It also helps explain why its greatest king never needed to wear a crown.