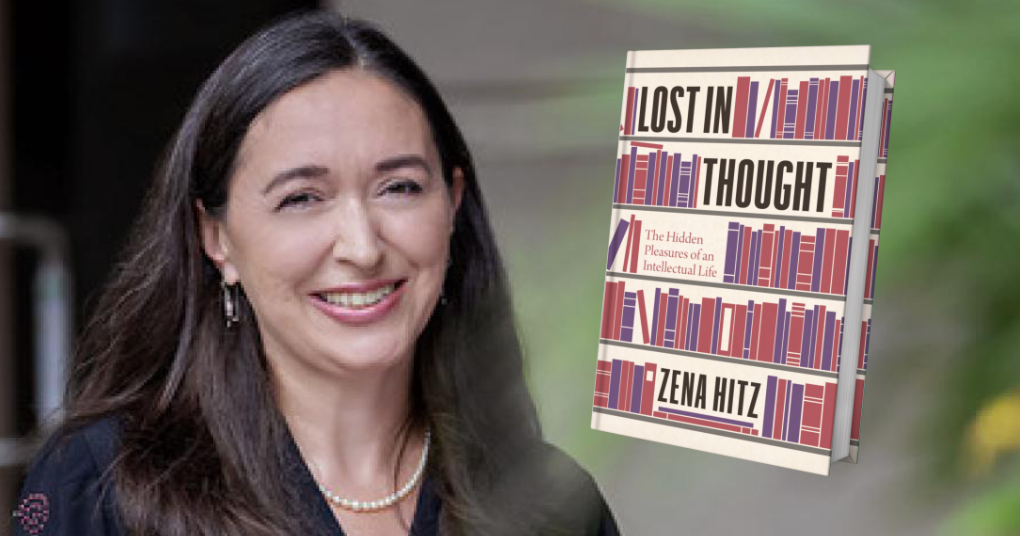

Lost in Thought: The Hidden Pleasures of an Intellectual Life

Zena Hitz

Princeton University Press

2020

240 pages

Published in 2020 by Princeton University Press, the book Lost in Thought: The Hidden Pleasures of an Intellectual Life by the North American professor Zena Hitz captivates from its first page. The prologue (pp. 1-24) is subtitled How Washing Dishes Restored My Intellectual Life and in those pages the author recounts her childhood – full of books and nature – her academic studies, her work as a professor of ancient philosophy and then, at the age of thirty-eight, entering a remote religious community called Madonna House, to the east of the forests of Ontario (Canada), and how from there she decided to return to the college of her youth to teach the classics.

In that prologue she describes her studies in St John’s College and then at three different universities until she got a stable job at a university in the southern United States, focused entirely on American football. There she began to work as a volunteer in hospices, refugee centres and programs to teach reading. “This person-to-person service was like a slow drip of water on a dry sponge.” (p. 13). Around this time, her inner Zena Hitz decided that she needed to have a religion since she had grown up without one, despite belonging to a Jewish family. She didn’t like the various churches she went to, but one Sunday she attended Mass at the local Catholic parish and everything changed. She was baptised during the Easter Vigil of 2006.

Shortly thereafter, Hitz transferred to another university in Baltimore, where she was deeply struck by the suffering of the poor and needy, which contrasted so much with the superficiality of academic life in an elite American university. She taught classes on Plato, Aristotle and contemporary ethics to large groups of students and received a comfortable salary and excellent benefits, but that kind of life seemed very poor to her: “The teaching that formed the central activity of my professional life seemed nothing like the lively and collaborative pursuit of ideas that had enchanted me as a student” (p. 17). The academic organisation made effective dialogue and communication between professors and students almost impossible. Faced with this crisis, Zena Hitz sought help for her vocation discernment and she decided to enter Madonna House. She spent three years in the Canadian community, dedicated to the contemplative life and to the manual tasks of the monastery, including washing dishes.

This biographical presentation helps us to appreciate the power of the book. “Learning” writes Hitz, “is a profession…. But it begins in hiding: in the inward thoughts of children and adults, in the quiet life of bookworms, in the secret glances at the morning sky on the way to work, or the casual study of birds from the deck chair. The hidden life of learning is its core, what matters about it. If computers were to collect and organize everything called knowledge – never mind whether it really is knowledge or not—such a collection would be pointless if it did not culminate in someone’s personal understanding, if it did not help someone to think about things, to work something out, to reflect…. There are other ways to nurture the inner life: playing music, or helping the weak and vulnerable, or spending time in nature or prayer – but learning is a crucial one” (p. 22).

As the book’s publisher announces on the back cover: “Lost in Thought” is a passionate and timely reminder that a rich life is a life rich in thought. Today, when even the humanities are often defended only for their economic or political usefulness, Hitz says our intellectual lives are valuable not despite but because of their practical uselessness.”

The central thesis of the book has captivated me because it invites us to rethink the role of universities and humanistic teachings in our society: “[Good teaching] has nearly disappeared from our college campuses, surviving only thanks to hardy, dedicated, principled individuals, who eke out their beautiful work without recognition or adequate recompense” (p. 199). “It is my hope that our institutions that support intellectual activity will recover their original purpose, as they need to in order to flourish…. We must reconnect with and remind ourselves of what matters in what we do, so that this particularly human way of being, its joys and sorrows, its modes of excellence, and its unique bonds of communion, is not lost” (p. 200).

To give a graphic example, compared to the somewhat grandiose image of the School of Athens in Raphael’s rooms that we aspiring intellectuals usually look at, Hitz defends “a lesser-known image of intellectual life, although much older and more common in European art, features a teenaged girl who loved reading” (p. 60).

Hitz is referring to the Virgin Mary and in her beautiful description she goes through some of the most wonderful paintings of this artistic tradition: from Van Eyck’s altarpiece in Ghent in which Mary appears crowned and jewelled as a queen, looking at a codex on her hands, to the scene of the Annunciation in the paintings by Filippo Lippi, Fra Angelico or Matthias Grünewald, in which the young Mary awaits the visit of the angel reading a book, perhaps even that passage from the prophet Isaiah in which it is said that a virgin will conceive a child (Is. 7, 14). According to Christian tradition, Mary was versed in the Hebrew scriptures; she had studied the law and meditated on the prophets. Mary knew the intellectual life, she enjoyed inner vitality.

In the consumerist society which is America, this fascinating book has drawn attention in defence of intellectual life, because it aspires to restore the genuine meaning of learning and study.