Mother Teresa: The Saint and Her Nation

Gëzim Alpion

Bloomsbury

2020

296 pages

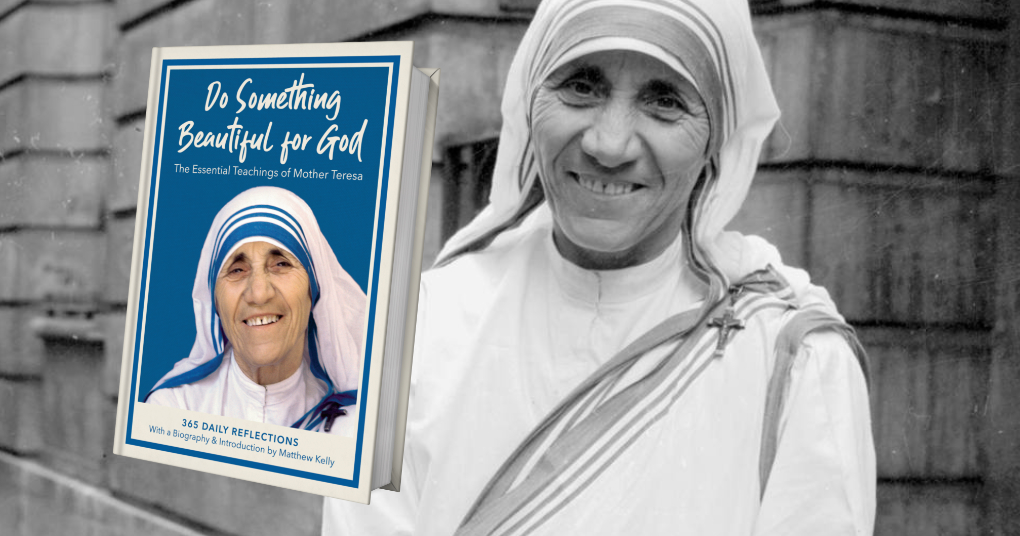

“By blood, I am Albanian. By citizenship, an Indian. By faith, I am a Catholic nun. As to my calling, I belong to the world. As to my heart, I belong entirely to the Heart of Jesus.” This modest autobiography could belong to no one other than Gonxhe Bojaxhiu, better known around the world as Mother Teresa. Long before her death in 1997 and her elevation to the status of a Catholic saint in 2016, Mother Teresa fascinated biographers. Malcolm Muggeridge’s BBC studio interview in London in 1968, followed by a 1969 documentary filmed in Calcutta and a 1971 book, Something Beautiful for God, launched what might almost be described as a Mother Teresa industry.

Gëzim Alpion is an Albanian-born academic at the University of Birmingham, in the UK, whose interests include the sociology of religion and of celebrity. Mother Teresa: The Saint and Her Nation is his second book about his famous compatriot. He is regarded as “the most authoritative English-language author” on her and “the founder of Mother Teresa Studies” – even though he doesn’t follow any faith, describing himself as a “spiritual rationalist”. Others have written about her good deeds and her spirituality; Alpion examines her Albanian identity.

This angle is almost always forgotten, as Gonxhe Bojaxhiu left her home in Skopje (which is today the capital of the republic of North Macedonia) when she was eighteen and today is completely identified with India. She never imagined that people would regard her as the greatest Albanian since the medieval warlord and patriot Skanderbeg (1405-1468). In fact, Alpion discovered that she swore to her mother when she left that “I will never speak in Albanian until we meet again.” And she kept that promise, within the bounds of civility. She never did see her mother again. She had a cousin and adopted sister, Filomena, whom she loved dearly, who migrated to Australia. Mother Teresa visited her in 1969, and insisted on speaking English, even though Filomena had never mastered the language. Even during eight trips to Albania late in her life, she spoke in English.

Alpion unravels this mystery by reviewing the ceaseless pain of Albanian history and digging into the saint’s background on both sides of her family. Albanians cannot reminisce about a glorious past as a powerful empire, as other small European countries can – the Bulgarians, the Armenians, the Greeks, Venice or Lithuania. Periodic invasions and persecutions by Serbs and Turks have sent waves of Albanian migrants fleeing both east and west. In Syria there are – or used to be, before the chaos of its barbarous civil war – small communities of ethnic Albanians called the Arnaut. In Italy there are enough small villages of Albanian speakers to justify two Byzantine-rite, Albanian-speaking Catholic bishops.

People with Albanian backgrounds have played significant roles in history. Apart from Skanderbeg and Kemal Atatürk, Alpion makes a case for the Corsican adventurer Napoleon Bonaparte. And there have been four Popes from Albania or with Albanian backgrounds, most recently the eighteenth century pontiff Clement XI (who was born Giovanni Francesco Albani).

In recent centuries, Albanian speakers have been crushed between the Orthodox Serbs and Greeks and the Muslim Turks, which accounts for the fact that only ten percent, more or less, of Albanians in Albania and Kosova currently identify as Roman Catholics. The Serbs wanted the Albanians to become Orthodox and the Turks wanted them to become Muslim. Unfortunately, for centuries the Vatican, which is just across the Adriatic Sea, was not prepared to defend Albanian Catholics, Alpion says. It had bigger fish to fry – a charm offensive with the Serbs.Ethnic cleansing and massacres continued into the twentieth century. As late as the 1950s, the governments of Yugoslavia and Turkey made a pact which would have allowed the expatriation of one million Albanians to Turkey. In the end about 100,000 were expelled. It was, comments Alpion, “state-endorsed human trafficking of the population of … entire regions of an ancient, homogenous nation”.

What does this grim background have to do with Mother Teresa? Alpion has dug deep into her family history and discovered that it is blood-stained and nationalistic. He is the first to publish the sketchy details. “Land of Albania! … thou rugged nurse of savage men!” sang the nineteenth century English poet Lord Byron. He wasn’t wrong. Gonxhe’s maternal great-grandfather, Pjetër Bardhi, was murdered in a blood feud. His son, Gonxhe’s grandfather, Ndue, avenged him and was murdered in his turn. Ndue’s son Gjon, Gonxhe’s uncle, was another victim of the blood feud. And then there was the ardent nationalism of Gonxhe’s businessman father, Nikollë. He worked to promote education in Albanian and lobbied to keep Albanian schools from closing down under Serb pressure. He even managed to secure funding for existing schools and for opening new ones. He opposed the creation of the kingdom of Yugoslavia which scooped up Albanian territory after World War I. This probably led to his death. In 1919 his business went bankrupt and not long afterwards he was poisoned after a political meeting in Belgrade. His final hours were agonising and traumatised the family, including nine-year-old Gonxhe.

Alpion believes that even Gonxhe’s name was a nationalist gesture. In Albanian it means “rosebud” or “little flower”. When she was born in 1910, both Slav nationalists and the Ottoman authorities frowned upon the use of the Albanian language. Naming their infant daughter Gonxhe was “a small but significant act of defiance”, Alpion believes. And her baptismal name, Agnes, was ostentatiously Roman Catholic.

This dark background was, as they say or used to say, “character-forming”, for Gonxhe. But in the wake of World War I there was more to come. Her mother’s brother Mark, a prosperous businessman, had four children. One of the sons died of the Spanish ’flu, then the heart-broken father, then another daughter and her husband, and yet another daughter. Finally Gonxhe’s grandmother died. Only Filomena, who came to live with Gonxhe and her mother Roza, survived. Alpion believes that these childhood experiences prepared Mother Teresa for her vocation in the Missionaries of Charity. “It was during those turbulent formative years in Skopje that Gonxhe’s lifelong gratitude to Jesus began. This was also the moment when she started thinking that the best way to show her thankfulness was to help people in distress. This was one of the reasons why she chose India as her destination when she learned about its poor from Balkan missionaries who had served there.”

All this new information suggests that Mother Teresa was well-prepared for what Catholic mystics call “the dark night of the soul”, in which she was shaken by doubts about God’s existence and his loving Providence throughout her long years as a nun.No one ever doubted that Gonxhe Bojaxhiu was a remarkable woman. This scrupulously researched study shows that she was even more remarkable than we thought. As Alpion concludes, “Mother Teresa’s life, ministry and legacy show the need to include ‘women’ in Thomas Carlyle’s contention that ‘the history of the world is but the Biography of great men’.”