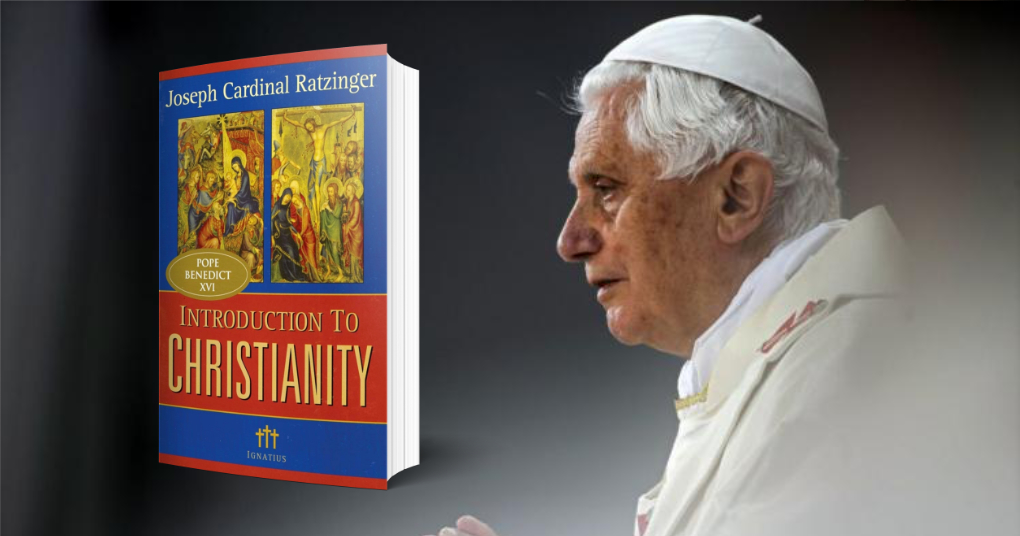

Joseph Ratzinger

Introduction To Christianity

2nd Edition (Communio Books)

Ignatius Press

2004

Joseph Ratzinger’s, Introduction to Christianity, is an extraordinary book. Reading it, one fully understands why some regard him as an Augustine for our age – or like St Augustine himself, for all ages.

Just as St Augustine in his City of God gave us a vision of the world as it was and as it should be, so did Ratzinger in his Introduction to Christianity. Written in the mid 1960s, and reflecting his thoughts from earlier in his career as a theologian and teacher, it was republished in the 1990s. Hardly a word had to be changed. It is not simply an introduction to the Faith embodied in Christianity; it is a portrayal of that Faith in the context of the world which God, in his providence, love and mercy chose to redeem.

But Ratzinger’s portrayal of the co-redemptive challenge facing Christians today contrasts with the world laid before us by Augustine in an important way: his is a text for an age in which a fatal rupture has arisen between these two cities, ideally complementary, in which mankind has its abode on this earth.

St Augustine was writing for us at the dawn of Christendom, within a century of the Roman Empire having given Christianity its stamp of approval. This might have seemed to some to be the arrival of the New Jerusalem. It was not. The City of God, among other things, spelled out how and why it was not. But from that date, while there were two cities co-existing uneasily, sometimes more, sometimes less, they were not pitted against each other as mortal enemies. The Heavenly City was God’s eternal kingdom, one in which all mankind could be citizens of on this earth while awaiting entry to a definitive and eternal citizenship in Heaven. While on earth the human race had a God-given privilege and responsibility to play its part in the Earthly City.

Ratzinger notes that believers in our age are sometimes said to look a little enviously at the Middle Ages, the height of Christendom. Then, it appeared, everyone without exception was a believer. But he suggests that historical research will tell us that even in those days there was a great mass of nominal believers and a relatively small number of people who had really entered into the inner movement of belief. History, he says, will show us that for many, belief was only a ready-made mode of life. In other words, for many, faith was a shallow thing.

Nevertheless, we would argue, despite the evil deeds perpetrated by them, the evidence of so many who sought repentance and did penance for their unfaithfulness suggests that faith abided in them, even though it were but like a grain of mustard seed. The Emperor Frederick II, thought by some to be an atheist and an antichrist, received the last rites on his deathbed and was interred dressed in the habit of a Cistercian.

So what has happened? How has “Western” civilisation, once called Christian, evolved to become one in which God is either denied outright or is accepted in forms of belief so laced with deceit that the reality of sin is denied?

Ratzinger asserts that part of the reason is our loss of our vision of all that is real, that we have come to see reality as the totality of what we can see, touch and feel, or prove by scientific experiment. God for “modern” man has ceased to be a “practical” God and is at best accepted as “just some theoretical conclusion of a consoling world view that one may adhere to or simply disregard. We see that today in every place where the deliberate denial of him has become a matter of principle and where his absence is no longer mitigated at all.”

Mankind’s folly in all this has led us into illusions about ourselves. At first, he writes, “when God is left out of the picture, everything apparently goes on as before. Mature decisions and the basic structures of life remain in place, even though they have lost their foundations. But, as Nietzsche describes it, once the news really reaches people that ‘God is dead’ and they take it to heart, then everything changes.”

The change, Ratzinger says, is evident all around us today. It is evident on the one hand, in the way that science treats human life: man is becoming a technological object while vanishing to an ever greater degree as a human subject. “When human embryos are artificially ‘cultivated’ so as to have ‘research material’ and to obtain a supply of organs, which then are supposed to benefit other human beings, there is scarcely an outcry, because so few are horrified any more.”

Then there is the cult of progress which, under the cloak of noble goals like the pursuit of health and happiness, demands that aberrant services be available. But, he asks, if man, in his origin and at his very roots, is only an object to himself, if he is “produced” and comes off the production line with selected features and accessories, what on earth is man then supposed to think of man? How should he act toward him? What will be man’s attitude toward man when he can no longer find anything of the divine mystery in the “other”, but only his own know-how?

Well, anyone who wants an answer to that question should read Aldus Huxley’s Brave New World.

What is happening in the “high-tech” areas of science, Ratzinger continues, is reflected wherever the culture, broadly speaking, has managed to tear God out of men’s hearts. “Today there are places where trafficking in human beings goes on quite openly: a cynical consumption of humanity while society looks on helplessly. For example, organized crime constantly brings women out of Albania on various pretexts and delivers them to the mainland across the sea as prostitutes, and because there are enough cynics there waiting for such ‘wares’, organized crime becomes more powerful, and those who try to put a stop to it discover that the Hydra of evil keeps growing new heads, no matter how many they may cut off.”

He then tries to bring us back to an acceptance of a broader sense of reality, a sense which does not exclude God and the supernatural simply on the basis that our human comprehension is challenged by it. He has no doubt that the alternative cannot but conjure up a horror scenario, only some of which he has laid before us. As an antidote to our delusions he simply asks us to just wonder whether God might not in fact be the genuine reality, the basic prerequisite for any “realism”, so that, without him, nothing is safe.

Karl Marx has played a central role in the disintegration we are looking at. Marxism is to Ratzinger what Manichaeism was to Augustine – a fatal misreading of humanity and its destiny. “Anyone who accepts Marx (in whatever neo-Marxist variation he may choose) as the representative of worldly reason not only accepts a philosophy, a vision of the origin and meaning of existence, but also and especially adopts a practical program. For this ‘philosophy’ is essentially a ‘praxis’, which does not presuppose a ‘truth’ but rather creates one.”

The fall of many of the communist regimes which blotted the history of the twentieth century did not, sadly, result in the disappearance of the Marxist philosophy which was at their foundation. Their bankruptcy was by many naively blamed, not on their Marxist roots but on a human misreading of those roots. Marx’s dialectical materialism asserted the primacy of politics and economics as the real powers that can bring about salvation and determine the future as it should be, keeping us all on “the right side of history”.

This primacy meant, above all, Ratzinger argues, that God could not be categorised as something “practical”. “The ‘reality’ in which one had to get involved now was solely the material reality of given historical circumstances, which were to be viewed critically and reformed, redirected to the right goals by using the appropriate means, among which violence was indispensable.”

This is the philosophy underlying the progressive culture and politics of our age. And the violent option? Yes. Evident for example, as Sohrab Ahmari and others point out, to give a specific instance, in the neutral, if not approving, stance of America’s progressive establishment of the murderous violence perpetrated in the aftermath on the killing of George Floyd. This contrasted with the same establishment’s exaggerated horror at the so-called insurrection of 6th of January, 2021.

From the Marxist and progressive perspective, speaking about God belongs neither to the realm of the practical nor to that of reality. The figure of Jesus in the progressive scenario is now no longer the Christ, but rather a heroic embodiment of all the suffering and oppressed calling us to rise up, to change society.

In the initial stages of this flight from God and from visions of the divine, God was not explicitly denied. Ratzinger says that God simply had nothing to do. The question of God was just not a practical one for the long-overdue business of changing the world. Has not Christian consciousness, he asks, acquiesced to a great extent – without being aware of it – in the attitude that faith in God is something subjective, which belongs in the private realm and not in the common activities of public life where, in order to be able to get along, we all have to behave now as if there were no God. In the public arena we now no longer have room for, in Ratzinger’s words, the “God who judges and suffers, the God who sets limits and standards for us; the God from whom we come and to whom we are going”.

All this is the context in which Ratzinger introduces us to the Credo by which Christians set out to live. It is deep – and difficult enough – but battling with its difficulty is truly rewarding. It is a text which makes it clear that the hope of our redemption rests with our assent to the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth of each and every article it lays before us.