It is probably not the most original plot-line you have ever encountered in science fiction – our heroes in their orbiting spacecraft fly off out of gravity’s pull and face death hurtling into the universe. David Bowie’s Space Oddity was always going to be a hard act to follow.

But taken in juxtaposition with the reflections of Romano Guardini in The Faith and Modern Man – written back in 1944 – it is intriguing as a metaphor for the human condition and the choices humans confront as we hurtle through the years of our existence in – or around – this planet.

For All Mankind is what is known as a space opera. It is currently streaming on Apple TV+. It is good in parts – if you can bear with its embedded nod to wokeness and have a sufficiently tuned detector to deal with the moral ambiguity which wokeness now almost invariably carries with it as baggage. But deep down this is a work about the human sacrifices we make to fulfil our ambitions. The answers it gives only take us so far. God does not get much of a nod – he’s not in the woke canon.

The episode which resonated in the context of what Guardini has written about the destiny of mankind tells the story of two astronauts on a rescue mission to a space station on the moon. They sustain damage to their craft and suddenly find themselves slipping out of orbit. They are in big trouble because they don’t have enough fuel to propel themselves out of danger.

Compounding their problems, they have also lost contact with ground control. Facing them is certain death. They then discuss whether to face death by starvation as they hurtle into outer space, or hasten their deaths by jettisoning themselves from their craft. With just a sliver of hope they make a last desperate call for help. Against all the odds they make contact and help comes under the guiding hands at Houston. That sliver of hope grows exponentially. Enough not said here to avoid a spoiler, I hope.

Try to read the story as a parable. I’m not suggesting that this is the intention of the show’s creators. My interpretation is a personal one prompted by a serendipitous encounter with Romano Guardini’s more transcendental reflections on mankind’s nature and needs.

Our heroes are not unlike the members of the human race with whom Guardini preoccupies himself in The Faith and Modern Man. Like our two astronauts, he sees us as creatures making our way through a beautiful but dangerous universe. For reasons beyond our control, “stuff happens” to us and we have to respond to it, or be helped to respond to it, in one way or another.

In many predicaments in which we find ourselves in life there may appear to be no “win-win” options open to us. We may see “lose-win” options or only “lose-lose” options. If however, we read the human condition with a truly Christian vision of life “winning is always among the options. The “win-win” condition of the Christian in this world is that of a “hundredfold” in this life and eternal happiness in eternity. The “lose-win” scenario is also one of hope. It is that of the person who does not know the truth of existence but who by the grace of God and the help of some human agency eventually sees the meaning of life and departs this world in the full knowledge and acceptance of the creator’s will.

The “lose-lose” scenario is the tragic one, brought about by the wilful rejection of the truth of that purpose for which we have our being, and the subsequent drifting into outer darkness which that rejection inevitably entails.

Guardini sees the Christian in this world in the context of all mankind. Christian men and women are situated in life exactly as are all other human beings. Their bodies are made up of natural elements and are subject to natural laws. They live in the community of family and nation. They participate in the events of history, and share in the economic, scientific and artistic life of their time. Their dreams, thoughts, ethical motives, standards of right living, hopes of fulfilment, are like those of everybody else.

But then he makes a vital distinction. In their consciousness they have thoughts of another kind too – they know and believe in a God who created all things and guides people by his providential wisdom. They also know of redemption and of a new, radically different life which springs from it, which begins here on earth and finds its fulfilment in eternity. In other words, they know a reality to which the unbeliever is blind.

The radical difference between these two visions of reality is that the one thinks that he has “made”, more or less, the world in which he lives. Believers know that they did not. Christians know that the truth that underlies their consciousness, the kind of mind it speaks of, the way of life to which it calls for, is anchored on one reality, one definite person. This is Jesus Christ who claims to be the living revelation of the hidden God, the redeemer of the lost, the bringer of new life. A Christian is one who takes him at his word and accepts all the terms and conditions of the rescue proposed to him by Christ when, in one way or another, he cries out for help when he finds himself, as it were, lost in space.

Guardini tells the story of the Christian’s life in this way: “The Christian believer of whom we are speaking has, in some way, come upon Jesus Christ, either by steeping himself or herself in the sources which relate his history, or by having learned from others of his person and doctrine. They are convinced that Jesus Christ alone brings truth and salvation, that he alone sheds light upon the riddle of existence, that by his spirit alone can moral problems be solved, that he alone affords a final refuge to the human heart. The lives of such men and women consist of a whole in which two worlds intermingle – the natural life with its realities, and everything which Christ makes known of truth and wisdom, and the strength which he imparts. This unity let us call simply the Faith.”

Like our astronauts, the Christian in this world is very vulnerable. Faith for the Christian is life itself, Guardini explains. And, since it is life in the fullest sense, it must undergo repeated crises, crises which concern not merely a single part of a person’s life, but their whole nature – their mind and all their potentialities.

The crisis faced by our astronauts was the result of a mechanical failure. But its consequences made them face not just the prospect of their imminent death but the choice of how they should die. Had they taken the quick sharp shock option and not held on to the sliver of hope they had, they would have short-circuited the providence of mission control and the agents sent to save them.

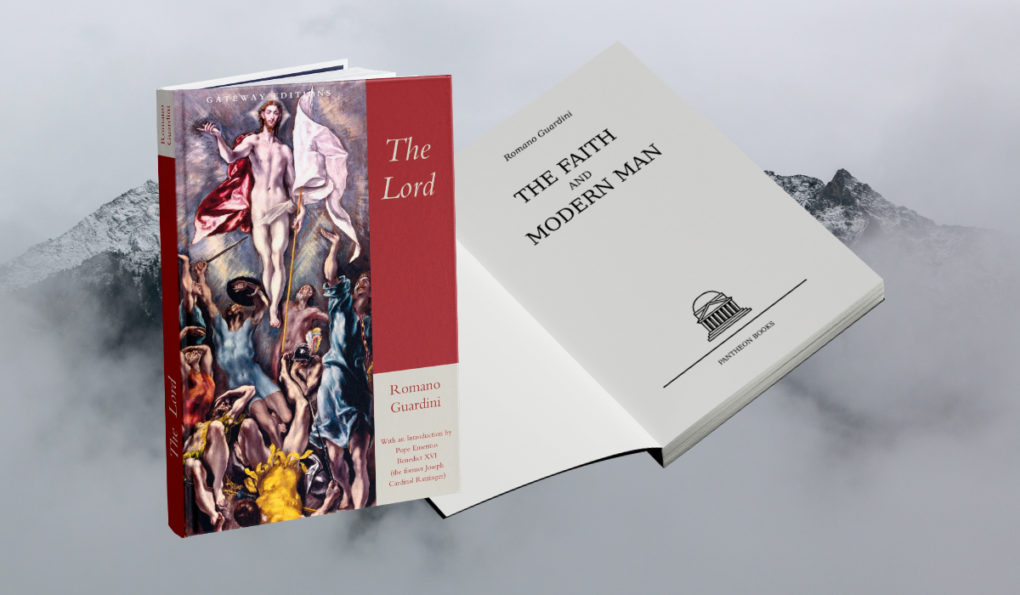

Sadly, believers can also short-circuit the providence which is their lifeline to salvation – by wilfully abandoning God and the Church which he instituted, what we might call ground control. In the matter of crises of faith Guardini writes of the role of the Church in the life of the struggling Christian. This is the Church whose nature and characteristics he elaborates on in another work, The Lord, written in 1937. The Church is, he says, the fullness of grace functioning in history, “Mystery of that union into which God, through Christ, draws all creation. Family of the children of God assembled about Christ, the firstborn. Beginning of the new holy people. Foundation of the Holy City once to be revealed. And simultaneous with all her graces are her dangers: danger of dominating, danger of ‘the law’. When we speak of the Church, we cannot ignore the fact of Christ’s rejection, which never should have been.”

This Church, he tells us, asks people in crisis – moral or otherwise – not to set aside their faith, even for the time being. This is based on the conviction that faith proceeds primarily not from human beings, but from God, whose power helps them to see as far into the question as is necessary and still to remain closely bound to God. He identifies two sides of the relation of a person’s heart to God. On the one side is longing for God, longing for his sacred truth. But on the other side is aversion, distrust, irritation, revolt. It is this twofold aspect which makes religious doubt dangerous, because the moving force in this doubt is hostility toward God.

“Therefore, in any struggle with doubt, one must resort to prayer. The most effective kind of prayer is that in which we place ourselves, in our hearts, before God, relinquishing all resistance, letting go of all secret irritation, opening ourselves to the truth, to God’s holy mystery, saying over and over again, ‘I desire truth, I am ready to receive it, even this truth which causes me such concern, if it be the truth. Give me light to know it, and to see how it bears on me.’”

This prayer is the equivalent of the two astronauts’ call for help, in hope against hope. The simplicity of that call – or prayer – completely belies its power to overcome the most devastating forces facing mankind, in or outside this world, natural or preternatural. It has the power to make all the difference between life and death, between light and outer darkness.