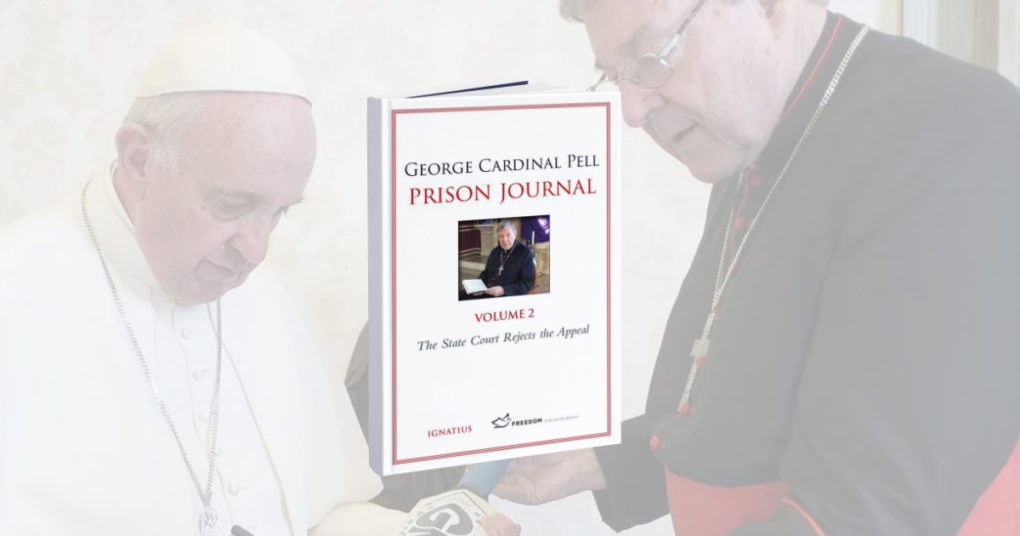

Prison Journal. Volume 2: The State Court Rejects the Appeal.

George Cardinal Pell

Ignatius Press

San Francisco

2021

319 pages

The first volume of Cardinal Pell’s Prison Journal covered the period from his imprisonment in February 2019 until July of the same year. This second volume continues the story from July to November 2019. A third volume will follow, covering the final months of Pell’s imprisonment, and perhaps, at some stage in the future, the publishers might consider merging Pell’s three Prison Journals into one volume.

As in the first volume, each day’s entry in this book reflects on Pell’s experience in solitary confinement in the Melbourne Assessment Prison and on a great variety of historical and contemporary topics, and concludes with a prayer.

Early on in this account, there is the crushing disappointment of the rejection by the three-judge Supreme Court of Victoria, on a two to one verdict, of the Cardinal’s appeal. He admits that he was “astonished and badly upset”. Nevertheless, the powerful dissenting judgement of Justice Weinberg provides significant consolation.

In a short period, the Cardinal’s combative spirit revives and he focuses on the inadequacies and “dismal legal performance” of the majority judgements. Towards the end of the book, the Cardinal receives the good news that his appeal to the High Court (Australia’s highest court) has been allowed. His successful appeal occurred in April 2020 but is not covered in this volume.

Around the time of his first appeal, Pell considers abandoning his journal but eventually decides to stick with it and recogniSes that the process of writing this daily reflection is helpful to him. A good deal of the book is naturally devoted to the Cardinal’s appeal – the wait for the first unsuccessful appeal and then the effort to apply for, and prepare, the High Court appeal. He is in regular contact with his legal team, some of whom visit him in prison.

He maintains that the majority decision in the first appeal “reversed the requisite onus of proof, requiring the defence to prove innocence and requiring the prosecution only to demonstrate possibility” (p. 131). He wishes to clear his name, not only for his own sake but more fundamentally for the sake of the Church and its mission.

The Cardinal received thousands of letters – “candles in the darkness” – while in prison and benefited from a global network of prayer, love and support. A nun in Wexford writes to him on the feast day of St Oliver Plunkett. An Irish bishop writes a “kind letter”. Chris Patten, the former British Governor of Hong Kong, who also wrote a report on Vatican communications, sends a message of encouragement via a friend.

The Cardinal’s experience of Mass is mostly confined to TV. The TV Mass does nourish him, even if he finds it very hard not to be able to celebrate or even to attend Mass himself. He is therefore deeply appreciative on one occasion when a priest friend is allowed to say Mass in his presence. He also receives nourishment from Protestant TV evangelists, while pointing out some gaps in their preaching.

There are amusing vignettes – Pell’s battle to get a haircut requires “weeks of high-level negotiations” but is eventually successful! There is also some self-deprecating humour. The Cardinal thus refers, with tongue firmly in cheek, to “my usual subtle and understated style”.

He works hard on his daily exercise routine and develops his table tennis and basketball skills pleasingly in solo practice. George Pell comes from a passionate sporting nation and is himself a huge sports fan and TV sport is one of his consolations in prison. Sport, he acknowledges, can be seen as an escapist pleasure. Nevertheless, it “is better than civil strife and revolution, and we are blessed by a society which provides the free time and facilities, the health and the wealth for these amusements”.

This second volume of the journal will appeal to Australians because of George Pell’s deep connections with the Church in Australia. However, the Cardinal has also become a much-respected figure in the universal Church so his book will also undoubtedly attract interest much further afield as well.

The Pell case is now very widely seen as a grave miscarriage of justice and readers from abroad who wish to find out more about the legal, media and political dimensions of this unedifying Australian episode can read this book in conjunction with the valuable analyses published by people like Fr Frank Brennan SJ, Michael Cook, Keith Windschuttle and Christopher Friel.

Fr Brennan, for example, has sharply criticised the Victoria Police and Director of Public Prosecutions and argued that their actions and failures caused the Cardinal and his accuser months of “unnecessary agony” and had negative consequences for genuine complainants and victims of abuse. The sheer implausibility of the case – that is, of the Cardinal and his alleged victims being physically present together when the abuse allegedly happened in a Cathedral sacristy – meant, Brennan argued, that it should never have come to trial.

Readers who are interested in the prison experience today will be impressed by the Cardinal’s faith and courage in a tough situation, where background noise often comes from the shouting of fellow inmates. He struggles at times against discouragement – “I do have to work harder to take each day at a time” – and the prospect of Christmas in jail is difficult but his prayer life nourishes him while his exercise routine and reading are also helpful. He is inspired by Christian writers like St Paul and his injunction to Timothy to “take your share of suffering for the sake of the Gospel” (2 Tim 1: 8); and argues that our deprivations can be joined to Christ’s for some good purpose.

Pell stands his ground on occasion when he considers that rules are being applied in a capricious way in the prison but his relations with the staff are generally good and he acknowledges “many small acts of kindness” from warders.

Those interested in the perspective of a prominent Christian on various current debates will find here a fascinating range of themes and topics, from the Roman Empire to the Jesuits, from the Church in Germany to sporting drama on the cricket field. A recurring theme is the importance of fidelity to the faith that has been handed down to us, ie, that Christians are not free “to reject or rewrite the apostolic tradition”.

The journal will also draw the attention of those who are interested in the finances of the Vatican. Although the Cardinal decided not to draw heavily in this book on his years working as prefect in the Economy Secretariat in Rome, he nevertheless offers significant comment on what is in the public domain, and notably on the Vatican’s huge annual deficit and on a “looming deficit” in its Pension Fund. He believes that chickens are coming home to roost and that hugely challenging times lie ahead for the Vatican finances. He sees the Vatican’s financial situation as a scandal of incompetence, exploited by criminals, and argues that a bankrupt Church could do nothing to help the poor.