Easter is an appropriate time for thinking about conversion. Mary Magdalen, the first witness to the Resurrection, and “apostle to the apostles”, was someone “from whom seven demons were cast out” (Lk 8,2). There are many other great conversions stories in the history of Christianity: Augustine, Ignatius, John Henry Newman, Paul Claudel, Edith Stein, Thomas Merton, Malcolm Muggeridge, to name but a few.

Sally Read’s recent conversion story, Night’s Bright Darkness, (Ignatius Press, 2016), was reviewed in these pages last August and is also testament to the power of the Holy Spirit. An English nurse and successful poet, Sally was a committed atheist but the writing of a book on women’s sexuality led her by a roundabout route to lively debates with a priest and eventually to conversion.

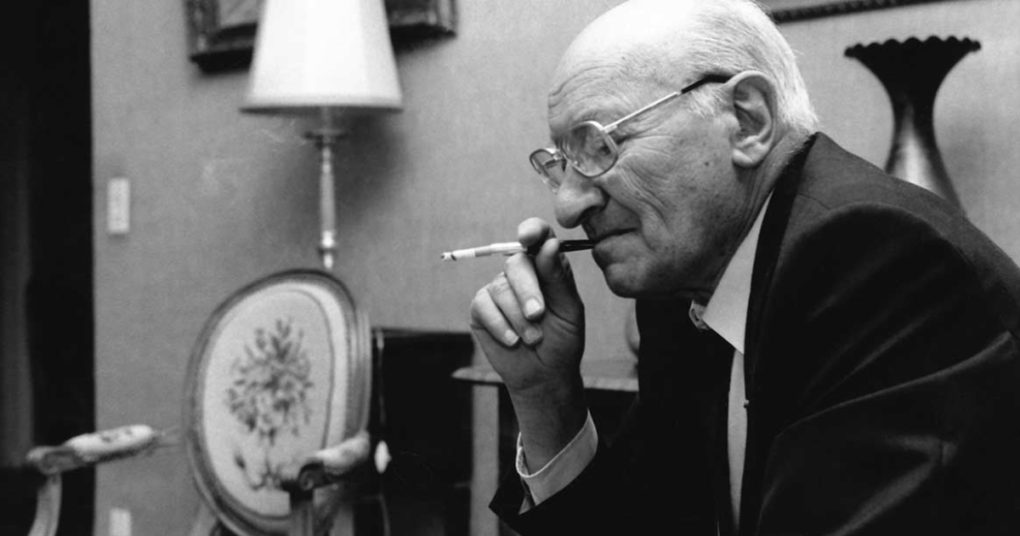

A conversion story that has always appealed to me is that of the French journalist and writer, André Frossard. Religion didn’t feature at all in his early life, even as something to rebel against. His non-religious parents came from secularised Protestant and Jewish backgrounds in the East of France and he was brought up in a village that had a synagogue but no Catholic church.

His parents had a strong faith, however, in socialism. His father, Ludovic-Oscar, was the first secretary-general of the French Communist Party and met Lenin in Moscow in 1920. He later left the party following disagreements with the international Communist organisation, the Soviet-dominated Comintern, but became a left-wing Government Minister in France in the 1930s.

In 1935, at the age of 20, André was, by his own account, a somewhat rebellious, insolent and lazy young man who often skipped classes during his teenage years. Having got a job in a left-wing newspaper, he became friendly with a Catholic colleague there and was waiting one July afternoon for his friend outside an adoration sisters’ chapel in Paris. Becoming impatient, he decided to enter the nondescript building in order to find his friend. He described the moment thus in his spiritual autobiography, God Exists. I have met Him (Herder and Herder, 1971 ): ‘It’s ten past five. In two minutes, I will be Christian.’

Entering the chapel, where the Blessed Sacrament was being exposed, he mysteriously heard the words “spiritual life” and suddenly had an overwhelming sense that God existed, that He was what Christians called “our Father”, that he was of an unparalleled gentleness, but a gentleness so active and strong that it was capable of piercing the hardest rock and even the hardest human heart.

God’s eruption in his life was accompanied by a deep joy, like the joy of a person rescued from a shipwreck. He experienced what he called “a silent and gentle explosion of light” and had a sense of belonging to a new family: the Church. He was conscious of receiving a “light of truth, a light that really instructs, that informs as it illuminates…. And the curious thing is that this wordless instruction is exactly the same as that of the Church” (Be Not Afraid!, The Bodley Head, 1984, p. 49).

Frossard’s conversion had a permanent impact on him and led to his baptism soon afterwards. His mother was impressed by the effect of her son’s conversion on his behaviour – the rebellious youth became a much gentler and more joyful person. Like his sister, she was to follow him afterwards into the Catholic Church.

His father, however, was perplexed by what had happened, particularly as some political opponents sought to embarrass him by publicising his son’s Catholic conversion. Ludovic-Oscar asked a medical friend to observe his son discreetly in the family home. The friend reported to his father that what had happened was an obvious case of “grace” – meaning religious hysteria! This, the doctor said, was a regular occurrence and was nothing to worry about. These feelings would ebb away in around two years and André would then again be as right as rain!

Although they hadn’t passed on the gift of faith to him, André felt loved by his parents and when the book of his conversion was published in France in 1969, he dedicated it to them.

Pope St John Paul II reflected on the conversion experience of both converts and “cradle Catholics” in the fascinating book-length interview (Be Not Afraid!) that he gave in the 1980s to André Frossard, who was by then a famous journalist with the French daily, Le Figaro.

In that book, John Paul commented on Frossard’s story, which he had read with great interest at the time of its publication: “You do not claim in any way to have seen God at the moment of your conversion. The title of your book means that you have experienced his action in you, that you have, so to speak, felt the inner touch of his light and his power…. You feel at the same time that you are yourself, possibly even more yourself than before. Your conversion has not deprived you of your personality; quite the contrary.” (p. 49)

John Paul added that he himself had not had the same dramatic conversion from unbelief to belief. He had always lived in an atmosphere of faith but added: “For me, the fundamental problem was not one of a conversion from unbelief to faith, but rather one of a transition from an inherited, received faith that was more emotional than intellectual to a conscious, fully mature faith given intellectual depth after a personal choice…. I am aware that in this long process, which is still going on, I am not alone” (p. 50).

Stories of conversion, in conclusion, are often very moving but also call to attention the ongoing need for conversion of “cradle Catholics” too and our need to value, and grow in, our Catholic faith just as much as converts do.

About the Author: Tim O’Sullivan

Tim O’Sullivan studied History and French and social policy and taught healthcare policy at third level. He is a regular contributor to Position Papers.