The release of A Hidden Life – for which filming began way back in 2016 – is finally bringing the story of Blessed Franz Jägerstätter to a global audience. During the Second World War, this Austrian farmer and devoted Catholic father and husband refused to fight for Nazi Germany. For this, he was imprisoned, and ultimately put to death. More than sixty years later, he was declared a martyr by the Church and beatified.

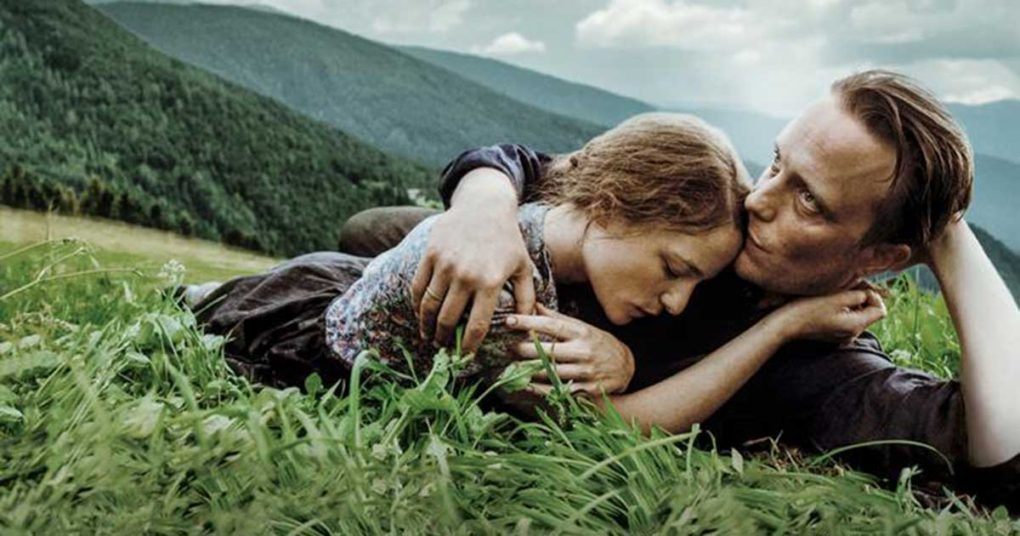

It is a timeless story, and in the hands of the writer and director Terrence Malick, it is told here with an extraordinary beauty and sensitivity. In the telling of such a tragic tale, it is probably hard to create a genuine warmth. Malick, however, achieves this from the opening few minutes where a snapshot of the lives of Franz (played by August Diehl) and his wife Fani (Valerie Pachner) in an idyllic Austrian village high up in the Alps. That same loving warmth between husband and wife is felt from the beginning right to the end, in spite of the terrible ordeal which Franz is put through.

Given the outstanding visual beauty of the mountains and meadows around them, it is no surprise that so much of the film is shot outdoors. Without any doubt, A Hidden Life is stunning, and the soundtrack is similarly moving. Never was Alpine beauty more breathtaking. The director uses natural beauty in front of us to demonstrate the striking contrast between the goodness in the world and a terrible evil which has overwhelmed one part of it. Franz and Fani’s doomed love story plays out in an environment where this evil lurks in the shadows.

As Fani steps out of the barn, her eyes are directed upwards by the ominous sound of a large airplane flying above. We do not see, but we know. It is the sound of war. At other times, the juxtaposition is less subtle. At night, we hear the quiet birdsong in the darkened fields, along with the voice of Hitler being played on a radio. The opening part goes a long way to setting the scene for the ordeal of the Jägerstätter family to take place.

In social standing and education, Franz does not stand apart from his fellows in any way. Though it becomes clear that he and his wife are religious, we learn along the way that this was not always so. His decision to refuse to fight for an evil regime is not tainted by the slightest hint of opportunism. Early on in the war after the conquest of France, we see him with a group of conscript recruits being made to watch a propaganda video highlighting Germany’s triumphs on the battlefield. The other young men are exultant, yet Franz is disturbed by what he sees. When the new recruits are demobilised and sent back to their farms, he questions other local men about what their country is doing to itself and to Europe. Stopped on the road by a man offering what appear to be valuables pilfered from one of the occupied nations, Franz walks on.

It was an important point for the director to make: after all, the real-life Franz had opposed Nazism from the very beginning, being the only person in his village on the Austro-German border to oppose the unification of the two countries. Whether Germany was winning or losing the war had no impact on Jägerstätter’s decision.

Faced with the knowledge that he will likely be recalled to military service, the central character then embarks on a period of deep reflection about what he will do. His opposition to Nazism is total, and is inspired by Germany’s aggression overseas, the killing of the disabled as part of the eugenics programme and the Nazi regime’s persecution of the Church. At first, his acts of resistance are small. He refuses to provide any donation in support of the war effort while also refusing to accept government benefits. He will neither support an unjust war nor will he profit from it. His stance soon raises the ire of the local Nazi mayor and others whose family members have left to fight.

This process accelerates throughout the movie with serious consequences for the entire family, who begin to be shunned by the other villagers. Other women spit on the ground when Fani walks past and their young daughters are ostracised by the village’s children. Still, Franz will not back down. Apart from his relationship with his wife, it is not made explicit where he derives the strength to continue to resist.

By all measures, he knows that he would be better off if he agrees to fight, as his father had done in the previous war. He knows the consequence of resistance is execution, thus leaving his wife and children without support. He seeks guidance from his parish priest and local bishop, both of whom are too browbeaten to join him in opposing the monsters who have taken over their country and made it monstrous in turn. The cross he bears he bears almost alone. Jägerstätter’s taciturn nature means that these discussions tend to be one-sided, with the other party being heard almost without reply.

There is, however, a deep conversation taking place, even though we cannot hear it. From the beginning of the process of resistance until the very end, many of Franz’s interlocutors – including the aforementioned parish priest, and the judge who will eventually pass sentence – pose a question: what will his resistance achieve?

It is a fair question.

In Hitler’s Germany, Franz’s stance meant death. It meant his wife became a widow and his children were raised without a father. The taking of one more innocent life made no difference to the government he was defying. Nobody outside of his own village – which had already rejected him – would know about it.

At a time when the China’s Catholics are debating their Church’s relationship with the secular authorities and the difficulties the current situation presents, there is no point pretending there are easy answers to such questions. Communist China is by any definition tyrannical. Every day, its government commits industrial-scale barbarism against innocent people, the Christian minority included. Choosing martyrdom by resisting their control completely would be a noble act for a Chinese man or woman. But an individual believer has other responsibilities: to help their family, to preserve their Church and to make the most of the life they have been gifted with.

Then consider the other point of view.

Among the four million men who died fighting for Germany in the war, there must have been a great many Christians who left their families and marched off to war with a heavy heart, knowing that their country’s leaders were committing great crimes. Had many more of them refused the oath to Hitler and the uniform and rifle that came with it, it would have made an impression. There would have been far more executions of conscientious objectors. But more Franz Jägerstätters and White Roses would have inevitably stirred up more resistance, and possibly created enough Count von Stauffenbergs to overthrow Hitler.

It is a hard question to answer and it is a luxury to be able to ponder it from afar.

A Hidden Life has received positive reviews in the secular press and has been awarded various prizes, including at Cannes. And yet for a film as good, by a director as renowned, there has been relatively little said about it. It raises the question as to whether a movie as spiritual in its focus can be appreciated by a secular audience. A story about the challenges posed to the individual conscience will always have a resonance with filmgoers, but this film is centred on the relationship between the martyr Franz Jägerstätter and the God he died for.

On countless occasions throughout the film, we are shown the pristine church and its white steeple and distinctive dome towering above the fields where the peasants of the village work. It is always there, often reminding us of its presence through the ringing of the bells. The family home is filled with religious iconography. Prayers are recited and references to Scripture are made by the main characters, acting as if they are narrators at crucial points.

As Franz considers his options before he is due to be called up, he walks alone along a country road and stops momentarily to look at a small crucifix erected on the roadside. He looks at Christ in his agony for just a moment, turns and continues onwards along the path he knows he must choose. The true battle here is not between an evil regime and the man they killed, but between an evil regime and the God whose power they could not overcome, and whose servant would not serve two masters. Languishing in prison, and asked by one of his captors whether he would like his freedom back, Franz’s answer is delivered without grandeur or emotion.

“I am free,” he says.